Author: Denis Avetisyan

Researchers have developed a rigorous benchmark to assess whether large AI models can genuinely understand and solve problems involving spatial relationships.

This work introduces MathSpatial, a framework and dataset for evaluating geometric problem solving and interpretability in multimodal large language models.

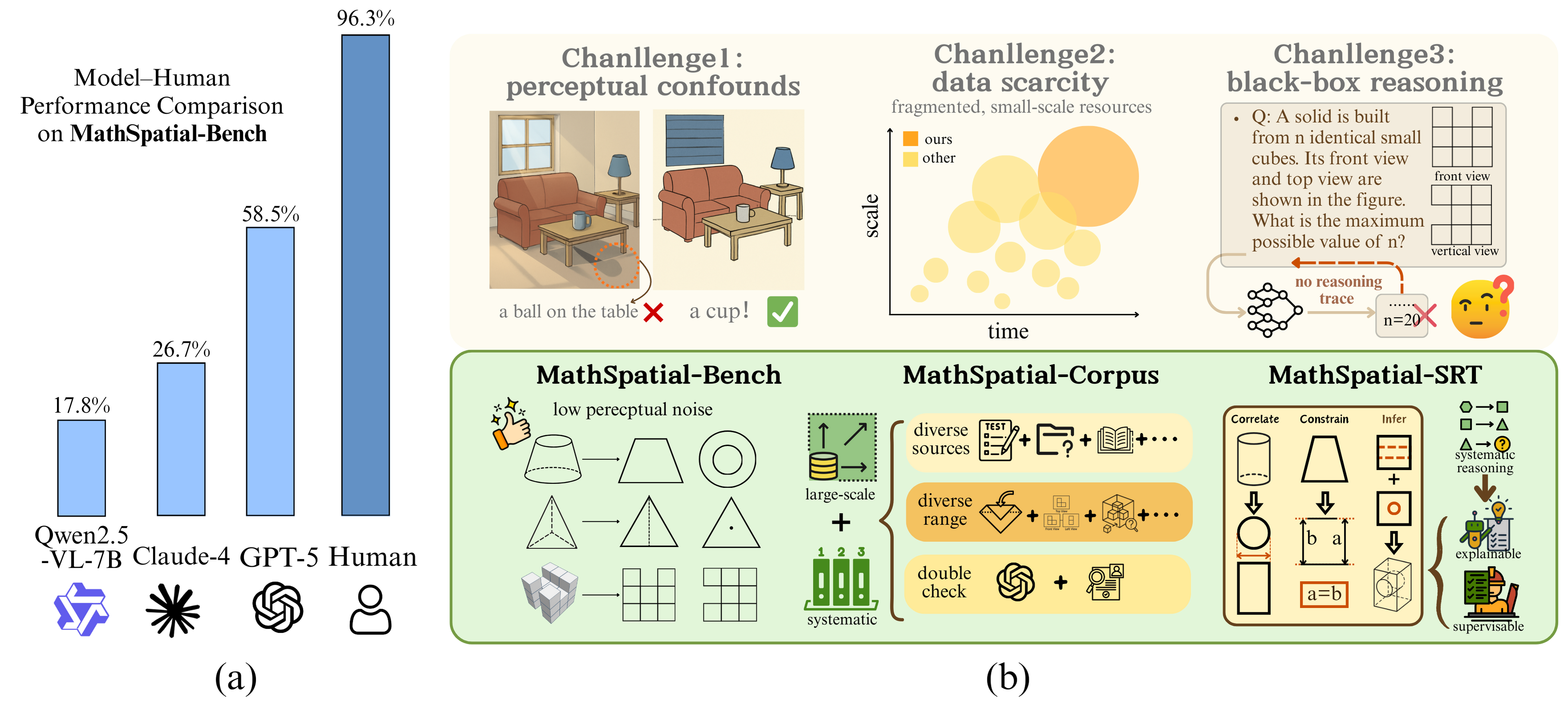

Despite recent advances in multimodal perception, current large language models struggle with fundamental mathematical spatial reasoning-the ability to parse and manipulate two- and three-dimensional relationships. This limitation is explored in ‘Do MLLMs Really Understand Space? A Mathematical Reasoning Evaluation’, which introduces MathSpatial, a comprehensive framework designed to rigorously evaluate and improve these capabilities. The authors demonstrate a significant performance gap between human and model accuracy on spatial reasoning tasks, and provide a new benchmark alongside a structured reasoning approach. Will disentangling perception from reasoning unlock more robust and interpretable geometric problem-solving in artificial intelligence?

The Persistent Challenge of Spatial Intelligence

Although artificial intelligence has achieved remarkable progress in areas like image recognition and natural language processing, consistently accurate spatial reasoning-the ability to understand and manipulate objects in three-dimensional space-continues to pose a substantial hurdle. This difficulty isn’t simply a matter of processing power; even with sophisticated algorithms and extensive datasets, AI systems often falter when faced with the ambiguities and complexities of real-world visual scenes. Unlike humans, who intuitively grasp spatial relationships, AI struggles with occlusion, varying perspectives, and cluttered environments, leading to errors in tasks requiring spatial awareness-from robotic navigation and object manipulation to understanding complex diagrams and interpreting medical imaging. The persistence of this challenge highlights a fundamental gap in current AI architectures, demanding innovative approaches to imbue machines with a more human-like understanding of spatial relationships.

Artificial intelligence systems frequently encounter difficulties when processing visual information due to the presence of perceptual confounds – extraneous details within an image that obscure the core elements needed for problem-solving. These distractions, such as varying textures, lighting conditions, or background clutter, can mislead algorithms trained to identify spatial relationships and patterns. Consequently, even relatively simple tasks requiring spatial reasoning – like determining the relative position of objects or predicting their movement – become significantly more challenging. Researchers are actively investigating methods to filter out these irrelevant features, allowing AI to focus on the essential components of a visual scene and improve the reliability of spatial analysis, ultimately bridging the gap between human and artificial spatial intelligence.

Contemporary multimodal artificial intelligence systems, while adept at recognizing objects and scenes, frequently falter when tasked with understanding the spatial relationships between them – a limitation stemming from an inability to break down complex spatial problems into discrete, manageable reasoning steps. These models often treat spatial challenges as a single, holistic perception rather than a series of logical deductions, hindering their capacity to generalize beyond familiar scenarios. Consequently, even seemingly simple tasks – such as predicting how an object will behave when rotated or determining the most efficient path through a cluttered environment – can prove surprisingly difficult. The inability to explicitly represent and manipulate spatial information as a sequence of reasoned steps represents a critical bottleneck in achieving truly robust and adaptable artificial intelligence.

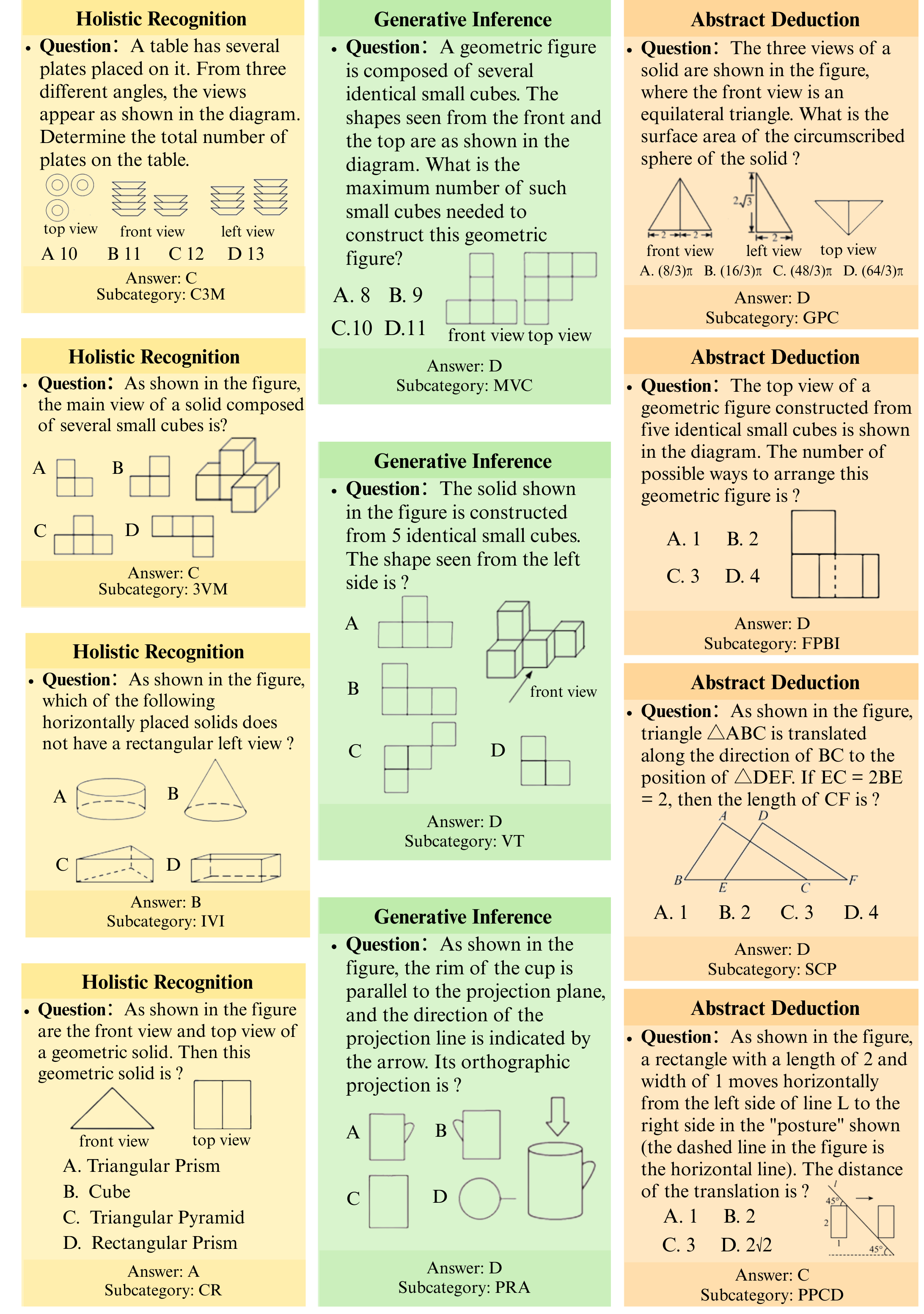

A Framework for Structured Spatial Reasoning

MathSpatial is designed as a comprehensive framework for both the assessment and improvement of mathematical spatial reasoning capabilities within multimodal large language models. It addresses a gap in existing benchmarks by providing a standardized methodology for evaluating how these models process and interpret spatial relationships within mathematical contexts. This unified approach facilitates consistent comparison of different model architectures and training strategies, enabling targeted advancements in their ability to solve problems requiring spatial understanding. The framework moves beyond simple visual question answering to focus specifically on the mathematical principles embedded in spatial arrangements, thereby promoting the development of more robust and reliable reasoning systems.

The MathSpatial-SRT framework decomposes spatial reasoning problems into three fundamental atomic operations. ‘Correlate’ identifies relationships between visual elements and their corresponding textual descriptions. ‘Constrain’ applies geometric or physical limitations to the problem, such as relative positioning or size restrictions. Finally, ‘Infer’ utilizes the correlated information and applied constraints to derive a solution or answer to the spatial query. This decomposition enables a modular approach to evaluating and improving model performance on specific reasoning steps, rather than treating spatial problem solving as a single, monolithic task.

Decomposition of spatial reasoning problems into atomic operations – specifically ‘Correlate’, ‘Constrain’, and ‘Infer’ – enables large language models to prioritize essential reasoning steps. By isolating these core operations, the framework minimizes the impact of extraneous visual information that may be present in the input data. This targeted approach improves model performance by reducing cognitive load and allowing the model to concentrate on the logical relationships necessary to solve the problem, rather than processing potentially distracting visual details. The result is enhanced accuracy and efficiency in spatial reasoning tasks.

![Unlike GPT-4o and Qwen2.5-VL-7B, which exhibit inconsistent reasoning, MathSpatial-SRT achieves a correct solution through structured reasoning based on atomic operations like [latex] ext{Correlate}[/latex], [latex] ext{Constrain}[/latex], and [latex] ext{Infer}[/latex].](https://arxiv.org/html/2602.11635v1/new_images/SRT-1-final.png)

Establishing Benchmarks and a Corpus for Spatial Reasoning

The MathSpatial-Bench benchmark is constructed to isolate and assess spatial reasoning capabilities by deliberately reducing the influence of perceptual factors. Traditional benchmarks often include visual complexity that can be solved through pattern recognition rather than genuine spatial understanding. MathSpatial-Bench utilizes abstract visual representations and focuses on problems requiring deduction of spatial relationships, transformations, and quantitative reasoning about geometry. This design prioritizes evaluating the core principles of spatial cognition, enabling a more accurate measurement of a model’s ability to reason about space independent of its perceptual processing capabilities.

The MathSpatial-Corpus is an 8000-problem dataset created to support and enhance the MathSpatial-Bench benchmark. This corpus provides large-scale supervised learning data specifically designed for training models in spatial reasoning. Crucially, each problem within the corpus is paired with structured reasoning traces, detailing the steps required to arrive at the solution. These traces allow for the development and evaluation of models capable of not just producing correct answers, but also demonstrating a logical and interpretable reasoning process. The dataset’s scale and the inclusion of reasoning traces are intended to facilitate advancements in model generalization and explainability within the domain of mathematical spatial reasoning.

The MathSpatial framework achieves a 22.1% accuracy rate on the MathSpatial-Bench benchmark, representing a 4.3% performance increase compared to baseline models. This result also positions the framework as superior to other currently available open-source models on this benchmark. For context, human performance on the MathSpatial-Bench is recorded at 96.3%, indicating a substantial gap remains between the framework’s performance and human-level spatial reasoning capabilities, but demonstrating measurable progress in automated spatial problem solving.

![MathSpatial-Bench comprises a diverse distribution of problem types, including [latex]24.2\%[/latex] geometry, [latex]21.7\%[/latex] arithmetic, [latex]17.6\%[/latex] algebra, [latex]16.8\%[/latex] measurement, [latex]12.1\%[/latex] data analysis, and [latex]6.0\%[/latex] mixed problems.](https://arxiv.org/html/2602.11635v1/new_images/benchmark.png)

Demonstrating Impact Through Model Fine-tuning

The open-source Qwen2.5-VL-7B model has undergone a significant enhancement in its ability to solve problems requiring spatial reasoning, achieved through a process called ‘Supervised Fine-tuning’. This technique utilized the MathSpatial-Corpus, a dataset specifically designed to challenge and develop these cognitive skills in artificial intelligence. By training the model on this curated corpus, researchers observed a marked improvement in its performance on tasks that necessitate understanding and manipulating spatial relationships, effectively enabling it to approach and solve complex problems with greater accuracy and efficiency. This focused training demonstrates the potential of targeted datasets to refine specific capabilities within large language models, paving the way for more robust and versatile AI systems.

The robustness of the training data for Qwen2.5-VL-7B hinges on a sophisticated validation process powered by GPT-4o within the MathSpatial framework. This isn’t simply about generating potential solutions; GPT-4o meticulously constructs detailed reasoning traces, outlining each step taken to arrive at an answer. These traces are then rigorously checked for logical consistency and accuracy, ensuring that the model learns from correct and well-justified examples. This dual function-generation and validation-minimizes the inclusion of flawed data, dramatically improving the reliability of the training set and, consequently, the model’s ability to perform accurate spatial reasoning. The resulting dataset is not merely larger, but demonstrably more trustworthy, fostering a higher level of confidence in the model’s outputs.

The implementation of structured reasoning traces (SRT) with Qwen2.5-VL-7B yields not only improved spatial reasoning but also a significant enhancement in processing efficiency. By organizing the model’s thought process into a defined, step-by-step format, the SRT method reduces the necessary token count for complex problem-solving by 25%. This compression stems from the elimination of redundant or implicit information, allowing the model to arrive at solutions with greater conciseness. The resulting decrease in token usage translates directly to faster processing times and reduced computational costs, making the fine-tuned model a more practical and scalable solution for applications requiring complex spatial understanding.

![Ablation studies on the MathSpatial benchmark reveal that performance gains from employing techniques like Base-CoT and SRT CoT are consistent across both [latex]3B[/latex] and [latex]7B[/latex] model scales.](https://arxiv.org/html/2602.11635v1/new_images/ablation.jpg)

The evaluation detailed within this work highlights a critical juncture in AI development; systems break along invisible boundaries – if one cannot see them, pain is coming. The MathSpatial framework, with its focus on structured reasoning traces, directly addresses the need to expose these boundaries within multimodal large language models. As Marvin Minsky observed, “You can’t always trust what you see; you have to trust how things work.” This sentiment resonates with the core idea of the paper: simply achieving correct answers isn’t enough. Understanding how a model arrives at a solution, particularly in spatial reasoning, is crucial for building robust and truly intelligent systems. The benchmark dataset and the emphasis on interpretability offer a pathway to illuminate these internal mechanisms and anticipate potential weaknesses before they manifest as errors.

Beyond the Map

The MathSpatial framework, as presented, doesn’t simply expose a lack of spatial understanding in current multimodal large language models – it illuminates a broader fragility. If the system survives on duct tape – patching together visual inputs with linguistic shortcuts – it’s probably overengineered. The benchmark itself isn’t the destination, but a diagnostic. It reveals that performance gains, absent a coherent internal representation of space, are likely brittle and transferable to only the most carefully curated scenarios.

A true advance requires moving beyond pattern matching. Modularity, in the context of reasoning, isn’t about dividing the problem; it’s about understanding the relationships between the parts. A system capable of genuine spatial reasoning must build, not borrow, its geometry. The current focus on scaling parameters offers diminishing returns if the underlying architecture remains fundamentally incapable of composing simple spatial transformations.

The path forward isn’t necessarily larger models, but models that reason about their own representations. Interpretable reasoning traces, as demonstrated here, are a critical first step. However, the ultimate goal must be a system where spatial understanding isn’t a post-hoc analysis, but an inherent property of the model’s structure – a foundational constraint, not an emergent behavior. Only then will these systems navigate beyond the map, rather than merely trace its lines.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.11635.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Star Wars Fans Should Have “Total Faith” In Tradition-Breaking 2027 Movie, Says Star

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Christopher Nolan’s Highest-Grossing Movies, Ranked by Box Office Earnings

- Jessie Buckley unveils new blonde bombshell look for latest shoot with W Magazine as she reveals Hamnet role has made her ‘braver’

- Country star Thomas Rhett welcomes FIFTH child with wife Lauren and reveals newborn’s VERY unique name

- eFootball 2026 is bringing the v5.3.1 update: What to expect and what’s coming

- Mobile Legends: Bang Bang 2026 Legend Skins: Complete list and how to get them

- Decoding Life’s Patterns: How AI Learns Protein Sequences

- Are Halstead & Upton Back Together After The 2026 One Chicago Corssover? Jay & Hailey’s Future Explained

- KAS PREDICTION. KAS cryptocurrency

2026-02-16 02:24