Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new study introduces Sage, a challenging benchmark designed to evaluate how well artificial intelligence can retrieve relevant information for complex research tasks.

The Sage benchmark assesses and improves retrieval performance for deep research agents, demonstrating the potential of corpus-level test-time scaling to overcome limitations in reasoning-intensive scientific literature search.

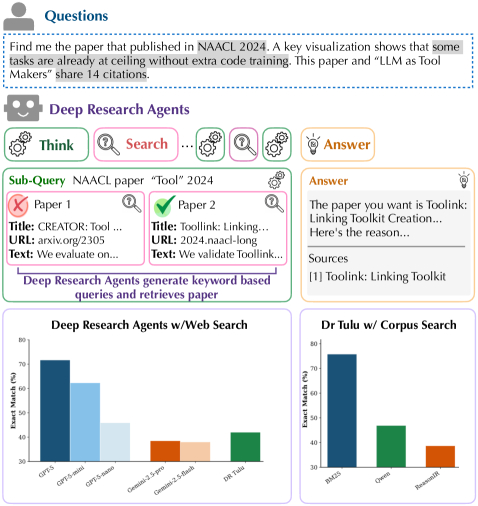

Despite advances in deep research agents and instruction-following LLM-based retrievers, a critical gap remains in effectively integrating these components for complex scientific inquiry. This work introduces ‘SAGE: Benchmarking and Improving Retrieval for Deep Research Agents’, presenting a new benchmark-SAGE-comprising 1,200 queries and 200,000 papers to evaluate retrieval performance within deep research agent workflows. Surprisingly, our analysis reveals that traditional BM25 retrieval significantly outperforms current LLM-based methods due to agents’ tendency to generate keyword-oriented sub-queries, but that corpus-level test-time scaling-augmenting documents with LLM-generated metadata-can yield substantial performance gains. Can these scaling techniques unlock the full potential of LLM-based retrieval for truly reasoning-intensive scientific discovery?

The Persistent Shadow of Simplicity

Despite recent advances in artificial intelligence, established information retrieval techniques continue to demonstrate surprising resilience in the realm of scientific literature. Studies reveal that BM25, a decades-old algorithm relying on term frequency and inverse document frequency, frequently surpasses large language model-based retrievers when addressing complex scientific queries – achieving approximately 30% better performance in certain benchmarks. This counterintuitive finding highlights a critical limitation of current AI systems: their struggle with the nuanced reasoning and synthesis required to navigate the intricate web of scientific knowledge, where simple pattern matching often falls short of true comprehension. The continued efficacy of BM25 suggests that, for many scientific tasks, a focus on statistical relevance remains surprisingly effective, even when contrasted with the sophisticated contextual understanding promised by contemporary AI.

The sheer volume and intricate detail of modern scientific literature present a significant hurdle for information retrieval systems. No longer sufficient is a simple matching of keywords; effective knowledge discovery now necessitates a capacity for deep understanding and synthesis. Research articles increasingly build upon prior work in complex ways, often implying relationships rather than explicitly stating them, and relying on nuanced experimental design and statistical analysis. Consequently, systems must move beyond identifying documents containing specific terms to actually interpreting the scientific claims, understanding the methodologies employed, and integrating information across multiple sources to answer complex queries. This shift demands computational models capable of mimicking the reasoning processes of scientists themselves, a task far exceeding the capabilities of traditional search algorithms.

Current evaluations of scientific reasoning systems often rely on benchmarks focused on factual recall – identifying whether a specific statement is supported by a given text. However, such benchmarks fail to capture the complexities of genuine scientific reasoning, which necessitates synthesis, inference, and the ability to connect disparate pieces of information. Consequently, researchers are developing new evaluation frameworks that present systems with tasks requiring more than simple fact retrieval; these include hypothesis generation from evidence, identifying logical fallacies in scientific arguments, and predicting experimental outcomes based on prior knowledge. Assessing performance on these complex tasks demands benchmarks that prioritize reasoning process rather than solely focusing on the correctness of a final answer, pushing the field toward more robust and meaningful measures of artificial scientific intelligence.

![Performance across diverse domains-Computer Science, Natural Science, Healthcare, and Humanities-demonstrates the model's ability to retrieve an average of [latex] ext{GT Documents}[/latex] relevant papers per query, regardless of query length in tokens.](https://arxiv.org/html/2602.05975v1/x10.png)

The Echo of Iteration: Deep Research Agents

Deep Research Agents signify a shift in automated scientific inquiry by moving beyond simple keyword searches to systems designed to replicate the iterative, multi-step reasoning processes characteristic of human researchers. Traditional automated systems typically provide direct answers to specific queries, while these agents are engineered to decompose complex research questions into a series of sub-problems, enabling them to explore a topic more comprehensively. This approach involves formulating hypotheses, identifying relevant evidence, synthesizing findings, and refining search strategies based on intermediate results – mirroring the cognitive steps undertaken by scientists during literature reviews and investigations. The intent is to facilitate more nuanced and insightful analysis of scientific data by automating the complex cognitive load typically associated with research.

LLM-based Retrievers form a core component of Deep Research Agents, enabling the processing of extensive scientific literature through iterative search and synthesis. These retrievers do not simply perform keyword searches; instead, they leverage large language models to understand the semantic meaning of both the initial query and the content of retrieved papers. This allows for nuanced filtering and the identification of relevant information even when terminology differs from the original query. The iterative process involves the retriever generating new search queries based on the content of previously retrieved documents, effectively refining the search scope and expanding the knowledge base. Retrieved information is then synthesized – not merely concatenated – to build a coherent understanding of the research landscape, identifying key findings, relationships, and potential gaps in knowledge.

Sub-query generation is a core function of deep research agents, enabling the decomposition of a complex initial query into a series of sequential, more focused sub-queries. This process facilitates iterative refinement of the search strategy; rather than attempting to answer the original question directly, the agent first identifies necessary background information or intermediate findings through these sub-queries. The results from each sub-query are then used to inform subsequent queries, allowing the agent to progressively narrow the scope and build a coherent understanding of the topic. This stepwise approach is critical for navigating the complexities of scientific literature and extracting relevant information that might be missed by a single, broad search.

The Landscape of LLM-Based Retrieval: A Chorus of Approaches

Current research is evaluating the efficacy of several Large Language Model (LLM)-based retrieval methods for scientific document search. These include Promptriever, which leverages LLM prompting for relevance scoring; ReasonIR, utilizing LLMs to reason about query and document relevance; LLM2Vec, employing LLMs to generate vector embeddings of documents; and GritLM, a method focused on grounding LLM responses in retrieved context. Each approach differs in its methodology for embedding documents and scoring their relevance to a given query, with performance being benchmarked on standard scientific retrieval datasets to assess their capabilities compared to traditional information retrieval techniques.

LLM-based retrieval methods employ diverse techniques for embedding and search. Some approaches, such as Promptriever, utilize instruction-tuning to align the language model with retrieval tasks, optimizing it to generate relevant embeddings based on natural language queries. Conversely, methods like LLM2Vec and GritLM leverage decoder-based generative models, treating retrieval as a sequence generation problem where the model predicts relevant documents given a query. This generative approach differs from traditional embedding-based methods by directly modeling the relationship between query and document tokens, potentially capturing more nuanced semantic connections. The choice between instruction-tuning and decoder-based models impacts both computational requirements and the type of semantic understanding applied to the retrieval process.

Corpus-Level Test-Time Scaling represents a technique for improving retrieval accuracy by dynamically adjusting the embedding vectors of documents within the corpus during the search phase. Evaluations have shown this method yields measurable performance gains; specifically, an 8% improvement in accuracy was observed on datasets comprising short-form questions, while open-ended question performance increased by 2%. This enhancement is achieved without requiring any modification to the underlying model weights, making it a computationally efficient method for boosting retrieval effectiveness.

The Sage Benchmark: Measuring the Echo of Reasoning

The Sage Benchmark establishes a demanding environment for assessing the reasoning prowess of advanced artificial intelligence agents. Unlike assessments focused on rote memorization, Sage challenges these systems with both concise, short-form questions requiring direct answers and expansive, open-ended questions demanding nuanced, detailed responses. This dual approach provides a comprehensive evaluation, probing not only an agent’s ability to retrieve information, but also its capacity for complex thought, synthesis, and articulate explanation. By utilizing these distinct question formats, the benchmark aims to differentiate between superficial performance and genuine understanding, offering a more reliable measure of an agent’s true research capabilities and potential for scientific discovery.

Current research involves a comparative analysis of leading deep reasoning agents – including DR Tulu, GPT-5, and Gemini-2.5-Pro – utilizing the Sage Benchmark. A key innovation within this evaluation is the implementation of corpus-level test-time scaling, a technique that enhances performance by leveraging information from the entire dataset during the question-answering process. Results demonstrate a notable improvement in agent capabilities; specifically, short-form question accuracy increased by 8% and open-ended question performance saw a 2% gain following the integration of this scaling method. These findings underscore the potential of corpus-level scaling to refine the reasoning abilities of advanced AI models and provide a standardized metric for assessing progress in the field.

A detailed assessment of deep research agent performance, such as that offered by the Sage Benchmark, reveals not simply which models achieve higher scores, but how they arrive at those results. Identifying specific strengths and weaknesses across different approaches – whether in factual recall, logical inference, or creative synthesis – is paramount for targeted improvement. This granular understanding allows developers to move beyond broad architectural changes and focus on refining specific capabilities, leading to more efficient progress in the field. Consequently, benchmarks like Sage are not merely comparative tools; they function as diagnostic instruments, guiding future research efforts and accelerating the development of more robust and capable artificial intelligence systems.

The pursuit of increasingly capable deep research agents, as detailed in this work concerning the Sage benchmark, feels less like construction and more like tending a garden. The paper highlights how even advanced LLM-based retrievers falter when faced with complex reasoning, a predictable failure given the inherent limitations of any system attempting to encapsulate the nuances of scientific inquiry. It’s a reminder that scaling corpus-level test-time performance isn’t about achieving perfection, but about fostering adaptability. As Alan Turing observed, “Sometimes people who are unkindest are the ones who hurt most.” Similarly, the limitations revealed by benchmarks like Sage aren’t flaws, but indicators of where the system-and its inevitable failures-will require the most careful cultivation.

What Lies Ahead?

The introduction of Sage is less a solution than a carefully constructed observation post. It charts not the triumph of retrieval, but the persistent fragility of connection. The benchmark reveals that even the most sophisticated language models, when tasked with genuine reasoning over scientific literature, stumble not on knowledge gaps, but on the treacherous terrain of context. Each successful retrieval is merely a temporary reprieve, a localized victory within a boundless wilderness of information.

The promise of corpus-level test-time scaling offers a palliative, not a cure. It suggests that the system’s understanding isn’t deepened, but broadened – a diffusion of attention, a strategic surrender to complexity. This is a growth, certainly, but of what kind? The system doesn’t learn to reason; it learns to appear to reason by amassing a greater perimeter of evidence. The silence following a successful query is not contentment, but reconnaissance.

Future work will inevitably focus on optimizing this scaling, on refining the algorithms that orchestrate the search. But the true challenge isn’t in finding more, it’s in finding less – in identifying the essential connections, the signal within the noise. The system will never truly ‘understand’ the literature; it will only become increasingly adept at simulating that understanding. And in that simulation, a different kind of failure will quietly take root.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.05975.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Clash of Clans Unleash the Duke Community Event for March 2026: Details, How to Progress, Rewards and more

- Jason Statham’s Action Movie Flop Becomes Instant Netflix Hit In The United States

- Kylie Jenner squirms at ‘awkward’ BAFTA host Alan Cummings’ innuendo-packed joke about ‘getting her gums around a Jammie Dodger’ while dishing out ‘very British snacks’

- Brawl Stars February 2026 Brawl Talk: 100th Brawler, New Game Modes, Buffies, Trophy System, Skins, and more

- Hailey Bieber talks motherhood, baby Jack, and future kids with Justin Bieber

- Gold Rate Forecast

- eFootball 2026 Jürgen Klopp Manager Guide: Best formations, instructions, and tactics

- MLBB x KOF Encore 2026: List of bingo patterns

- Jujutsu Kaisen Season 3 Episode 8 Release Date, Time, Where to Watch

- How to download and play Overwatch Rush beta

2026-02-07 14:33