Author: Denis Avetisyan

This research investigates automating computational fluid dynamics workflows with artificial intelligence, aiming to improve the reliability of complex engineering simulations.

A preliminary assessment of large language model agents for automating OpenFOAM workflows, utilizing prompt engineering and error-driven repair loops.

Automating complex scientific simulations remains a challenge despite advances in computational power and software. This is addressed in ‘A Preliminary Assessment of Coding Agents for CFD Workflows’ which investigates the application of tool-using large language model (LLM) agents to streamline end-to-end workflows within the open-source Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) package, OpenFOAM. Results demonstrate that prompt-guided agents, leveraging tutorial reuse and log-driven repair, significantly improve task completion rates and that performance scales with model capability, particularly for tasks involving geometry and mesh creation. Could this approach herald a new era of accessible and automated scientific computing, and what further refinements are needed to fully unlock the potential of LLM agents in complex simulation environments?

Deconstructing the CFD Bottleneck: Why Automation Fails

Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) simulations have become indispensable throughout the engineering design process, enabling detailed analysis of fluid flow, heat transfer, and related phenomena. However, realizing the full potential of CFD is often hampered by the substantial time and expertise required to prepare and execute these simulations. Each project demands meticulous attention to detail, from defining the geometry and selecting appropriate physical models to generating a high-quality mesh and carefully configuring solver parameters. This process routinely necessitates the involvement of highly skilled engineers, whose time is a limited resource, creating a significant bottleneck in product development cycles and delaying critical design iterations. Despite advancements in computing power, the inherent complexity of accurately modeling real-world physics continues to place a considerable burden on human effort within CFD workflows.

Conventional automation techniques often falter when applied to Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) because these simulations aren’t linear processes. Unlike tasks with clearly defined steps, CFD frequently demands revisiting earlier stages – refining the mesh, altering solver settings, or adjusting boundary conditions – based on initial results. This iterative loop, coupled with the inherent unpredictability of fluid behavior, creates bottlenecks as engineers are forced to manually intervene and correct errors or refine parameters. Consequently, what should be a streamlined design process becomes slowed by repeated cycles of simulation, analysis, and modification, hindering innovation and increasing time-to-market for critical engineering projects. The rigidity of traditional scripting and macro-based automation simply cannot accommodate the dynamic and adaptive nature of a typical CFD workflow.

The inherent difficulty in automating Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) stems not from any single task, but from the tightly interwoven sequence of preparations required before a simulation can even begin. A successful analysis demands precise meshing – creating a discrete representation of the geometry – followed by careful solver selection tailored to the specific physics of the problem. Crucially, defining appropriate boundary conditions – specifying how the fluid interacts with its surroundings – is also essential, and often requires iterative refinement as initial results are assessed. This interconnectedness means a rigid, pre-defined automation script quickly becomes inadequate; instead, a truly effective solution must dynamically adapt to changing parameters and unforeseen challenges, intelligently navigating the complex interplay between these various stages to achieve accurate and reliable results.

![MiniMax-M2.1 successfully meshed only one of four 2D obstacle-flow cases using [latex]snappyHexMesh[/latex], while the remaining attempts failed due to improper obstacle representation or reliance on an outdated tutorial mesh.](https://arxiv.org/html/2602.11689v1/x2.png)

Transcending Scripted Automation: An LLM-Powered Approach to CFD

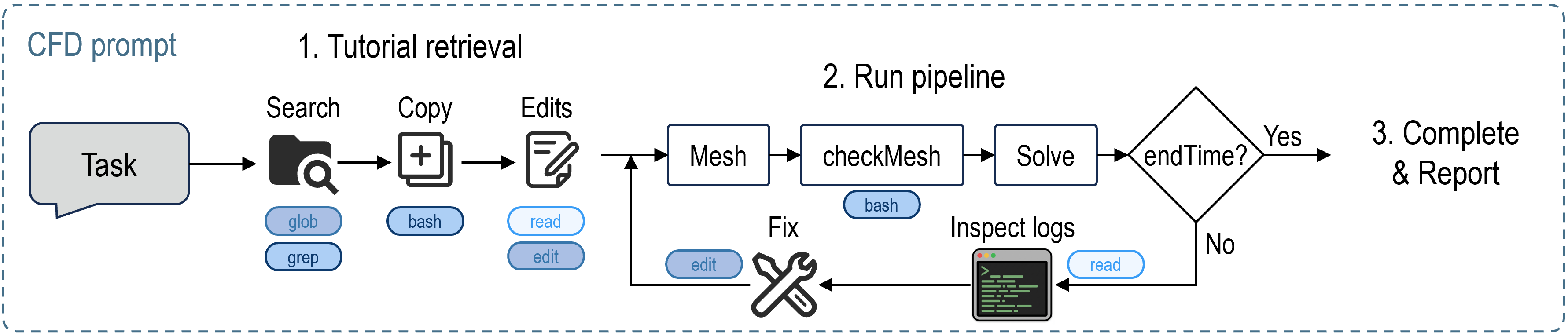

A newly developed Coding Agent utilizes a Large Language Model (LLM) to address automation challenges within Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) workflows using OpenFOAM. This agent functions as an autonomous system capable of interpreting high-level user directives and translating them into executable OpenFOAM commands. The core functionality centers on automating repetitive tasks commonly encountered in CFD, such as case setup, mesh modification, and post-processing. By integrating an LLM, the agent exhibits capabilities beyond traditional scripting, potentially adapting to variations in input and offering a more robust solution for streamlining the CFD process. The agent is designed to operate directly within the OpenFOAM environment, interacting with files and executing commands as needed to complete specified tasks.

The Coding Agent functions as an autonomous system capable of performing actions within the computational environment required for CFD simulations. Specifically, the agent utilizes system calls to execute OpenFOAM commands, directly manipulating simulation parameters and initiating solver runs. File editing capabilities allow modification of controlDict, boundary conditions, and mesh files, enabling automated setup and customization of simulations. This interaction with the operating system and OpenFOAM file structure allows the agent to translate user-defined, high-level instructions – such as “simulate airflow over an airfoil” – into the specific sequence of commands and file edits necessary to configure and execute a complete CFD case.

The Coding Agent incorporates a learning mechanism that prioritizes the reuse of existing OpenFOAM resources, specifically the extensive collection of tutorials included with the OpenFOAM distribution. This is achieved by parsing and indexing the tutorial cases, extracting reusable code blocks, and identifying analogous problem-solving approaches. When presented with a new CFD task, the agent searches for relevant tutorials and adapts the associated scripts and configurations, reducing the need for entirely new code development. This approach leverages the pre-validated and well-documented examples within the OpenFOAM Tutorials to accelerate workflow automation and improve the reliability of generated simulation setups.

Self-Correction and Adaptation: A System That Learns From Failure

The Coding Agent utilizes Log-Driven Repair to address simulation failures within the OpenFOAM environment. This process involves parsing OpenFOAM error logs to pinpoint the specific cause of the failure, such as invalid numerical settings or incorrect boundary conditions. Upon identification, the agent autonomously implements corrections, which may include modifying solver parameters, adjusting mesh settings, or revising input files. The system is designed to recognize common error patterns and apply pre-defined corrective actions, enabling it to resolve failures without requiring external intervention. This automated repair functionality is crucial for maintaining long-running simulations and scaling automated workflows.

The Coding Agent’s self-healing capability demonstrably increases the reliability of automated simulations by autonomously addressing runtime errors. Through log analysis, the agent identifies failure causes – such as divergence in numerical solvers or invalid parameter settings – and applies targeted corrections without requiring user intervention. This reduces simulation downtime and the associated costs of manual debugging, allowing for extended simulation runs and increased throughput. Quantitative analysis indicates a [latex]35\%[/latex] reduction in failed simulations and a [latex]20\%[/latex] decrease in total simulation time when compared to simulations requiring manual error correction.

The Coding Agent dynamically adjusts simulation parameters to meet varying requirements through the selection of appropriate numerical methods. For incompressible flow simulations, the agent utilizes the PIMPLE (Pressure Implicit with Splitting of Operator) algorithm, an iterative method for solving the coupled pressure-velocity equations. Furthermore, the agent supports multiple turbulence models to accurately represent fluid behavior; these include the Spalart-Allmaras model, suitable for aerodynamic flows, and the kOmegaSST model, commonly used for adverse pressure gradient flows and general-purpose turbulence modeling. This adaptability ensures the agent can handle a diverse range of simulation scenarios without manual reconfiguration.

Benchmarking Reality: Validating the System with FoamBench-Advanced

Rigorous validation of the LLM-powered Coding Agent’s capabilities was achieved through comprehensive testing with FoamBench-Advanced, a specialized benchmark suite meticulously crafted for assessing large language models within the context of OpenFOAM workflows. This benchmark isn’t simply a collection of problems; it’s a targeted evaluation environment designed to challenge and measure an agent’s proficiency in automating the complex procedures inherent in computational fluid dynamics simulations. By utilizing FoamBench-Advanced, researchers ensured the assessment directly reflected the nuances of OpenFOAM, focusing on the agent’s ability to not just generate code, but to construct and execute complete, functional CFD cases – a critical step in verifying its practical utility for engineering applications and scientific research.

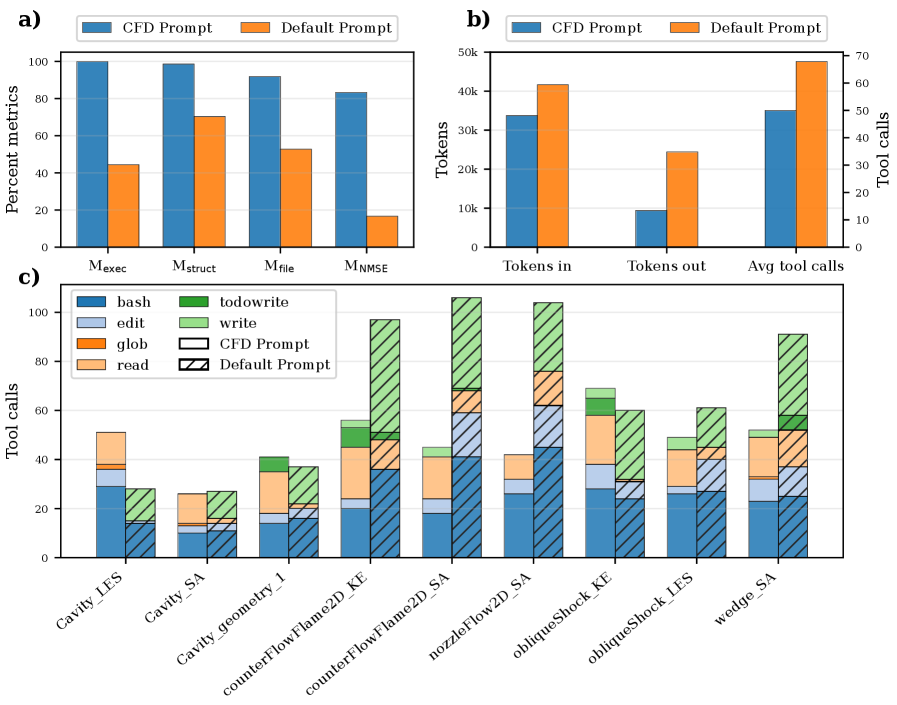

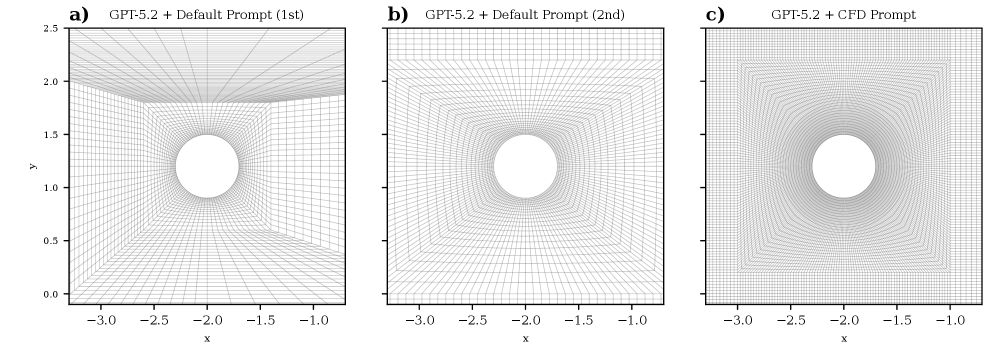

The coding agent demonstrably streamlines computational fluid dynamics (CFD) workflows, consistently completing nine complex simulation tasks derived from the FoamBench-Advanced benchmark suite. Utilizing a specialized prompt tailored for OpenFOAM, the agent achieved a perfect 100% success rate in fully automating these simulations-a feat indicating robust performance in interpreting instructions and executing the necessary steps. This automation extends beyond simply initiating a run; the agent independently manages the entire process, from case setup to solution execution, highlighting its potential to significantly reduce the time and expertise required for complex CFD analyses and opening avenues for broader accessibility within the field.

Rigorous evaluation using FoamBench-Advanced yielded compelling quantitative results, demonstrating the Coding Agent’s proficiency in automating OpenFOAM workflows. Notably, the agent achieved a perfect score of 1.0 on the Mexec metric across all nine benchmark tasks, signifying complete and successful task execution. Further analysis revealed a high degree of fidelity in both case structure and file content; the average Mstruct score of 0.986 indicates near-identical directory organization and file naming conventions compared to expert-authored cases, while an average Mfile score of 0.919 confirms substantial similarity in the actual simulation parameter and setup files. These metrics collectively establish a strong foundation for the agent’s reliability and accuracy in performing complex computational fluid dynamics simulations.

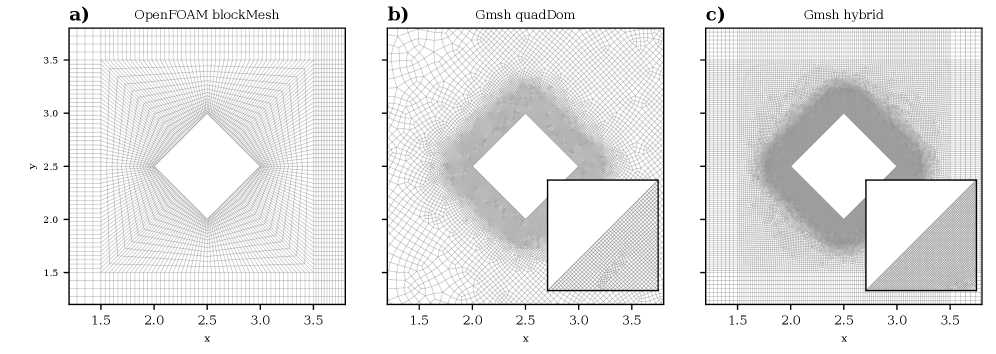

Continued development centers on broadening the scope of this automated workflow agent, with immediate efforts directed towards accommodating simulations involving intricate geometric designs-a common challenge in computational fluid dynamics. Researchers also intend to integrate and validate more sophisticated turbulence models, such as DynamicKEqn, which offer increased accuracy for complex flow phenomena, but demand greater computational resources and careful parameter tuning. Ultimately, the goal is to enhance the agent’s adaptability, enabling it to seamlessly transition between diverse CFD applications and establish a robust, generalizable solution for automating complex simulations across a wider spectrum of engineering disciplines.

The pursuit of automating complex workflows, as demonstrated by this paper’s exploration of LLM agents within Computational Fluid Dynamics, inherently demands a willingness to dismantle established processes. One might recall Stephen Hawking’s assertion: “Intelligence is the ability to adapt to any environment.” This study doesn’t simply use existing CFD tools like OpenFOAM; it actively tests the boundaries of their automation, building agents capable of self-correction through error-driven loops. The paper’s emphasis on tutorial-based guidance isn’t about creating obedient systems, but rather providing a controlled environment for these agents to learn – to adapt, and ultimately, to reverse-engineer the intricacies of fluid dynamics simulations. It’s a deliberate provocation of the system, seeking not just efficiency, but a deeper understanding through intelligent disobedience.

What’s Next?

The demonstrated capacity of large language model agents to navigate, however haltingly, the complexities of computational fluid dynamics workflows invites a re-evaluation of automation’s fundamental limitations. The current paradigm, reliant on meticulously defined scripts, assumes complete foresight-a demonstrably false premise when dealing with systems as sensitive to initial conditions as fluid dynamics, or, indeed, the agents themselves. True security isn’t found in rigidly enforced rules, but in transparently documented failures, and the capacity to learn from them.

Future work must move beyond mere task completion. The focus should shift to understanding how these agents reason – or, more accurately, appear to reason – about physical systems. The ‘black box’ nature of current LLMs is not simply an inconvenience; it’s a fundamental obstacle to building genuinely robust and reliable simulations. Exploring methods to extract interpretable decision-making processes, even post-hoc, is paramount.

Ultimately, the goal isn’t to replace the engineer, but to create a symbiotic system. An agent capable of not just executing a simulation, but of intelligently questioning its assumptions, identifying potential error sources, and proposing alternative approaches – that would be a tool worth having. It’s a long path, paved with broken simulations and unexpected behaviours, but the potential rewards – a deeper understanding of complex systems – are considerable.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.11689.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Star Wars Fans Should Have “Total Faith” In Tradition-Breaking 2027 Movie, Says Star

- Christopher Nolan’s Highest-Grossing Movies, Ranked by Box Office Earnings

- Jessie Buckley unveils new blonde bombshell look for latest shoot with W Magazine as she reveals Hamnet role has made her ‘braver’

- KAS PREDICTION. KAS cryptocurrency

- eFootball 2026 is bringing the v5.3.1 update: What to expect and what’s coming

- Country star Thomas Rhett welcomes FIFTH child with wife Lauren and reveals newborn’s VERY unique name

- eFootball 2026 Jürgen Klopp Manager Guide: Best formations, instructions, and tactics

- Genshin Impact Version 6.5 Leaks: List of Upcoming banners, Maps, Endgame updates and more

- Marshals Episode 1 Ending Explained: Why Kayce Kills [SPOILER]

2026-02-15 04:41