Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research reveals the challenges continuous attractor networks face in learning meaningful transitions, and how geometric constraints can limit their ability to represent complex environments.

This review explores the emergence, limitations, and topological constraints of successor representation learning within continuous attractor networks, with implications for understanding basal ganglia function and curriculum learning.

While recurrent neural networks are often proposed as substrates for representing cognitive maps and planning, a persistent challenge lies in distinguishing genuine attractor dynamics from transient, shortcut solutions. This is the central question addressed in ‘Learning Discrete Successor Transitions in Continuous Attractor Networks: Emergence, Limits, and Topological Constraints’, where researchers investigate the conditions under which continuous attractor networks (CANs) learn stable transitions between states without explicit displacement signals. Their findings reveal that enforcing stability over extended periods is crucial for eliciting attractor-based transitions, and that network topology imposes strict limits on learned representational capacity, particularly at manifold discontinuities. Can these geometric constraints be overcome through alternative architectures or learning paradigms, allowing CANs to robustly support complex, long-horizon planning?

The Fragility of Sustained Cognition

Conventional neural networks frequently falter when confronted with tasks demanding prolonged cognitive effort and the consistent preservation of internal states. These architectures typically rely on fleeting activation patterns – momentary spikes of neural firing – rather than establishing stable, self-sustaining representations of information. This reliance creates a fundamental limitation in scenarios requiring sustained thought, such as complex planning or reasoning over extended periods; the network struggles to ‘remember’ relevant information across multiple steps, leading to errors or inconsistent performance. Unlike biological systems capable of maintaining robust neural activity for extended durations, these networks exhibit a tendency towards transient responses, making it difficult to build reliable internal models of dynamic environments or complex tasks requiring continuous updates and adaptations.

The brain’s capacity for sustained thought relies not simply on activating neural pathways, but on establishing stable, self-reinforcing patterns of activity known as attractor states. Traditional artificial neural networks, however, often operate through fleeting activation patterns – transient signals that dissipate quickly. This reliance on impermanent activation hinders the network’s ability to maintain information over time, effectively short-circuiting complex cognitive processes like reasoning and planning. Unlike biological systems which can ‘lock in’ on a particular state and maintain it despite noise, these networks struggle to preserve crucial information needed for multi-step tasks, leading to unreliable performance and an inability to generalize beyond immediate stimuli. The result is a system prone to forgetting intermediate steps and failing to build coherent, long-term strategies.

Many current artificial neural networks demonstrate a propensity for what researchers term “impulse cheating,” a phenomenon where the system learns to exploit superficial cues or shortcuts to achieve high performance on immediate tasks without developing a genuine understanding of the underlying principles. This often manifests as near-perfect “successor accuracy” – the ability to correctly predict the next step in a sequence – but only when evaluated over short timescales. Upon extending the evaluation horizon, or introducing even minor variations to the task, these systems quickly falter, revealing that their apparent competence stemmed from memorizing transient solutions rather than internalizing the task’s dynamic structure. Essentially, the network learns what to do in the present moment, not why it’s doing it, creating a brittle intelligence incapable of robust generalization or long-term planning.

![While both Ring and Snake gaits initially appear successful under short-term evaluation, long-term analysis reveals the Ring's inherent stability compared to the Snake's systematic geometric failures at topological transitions, such as [latex]9 \to 0[/latex].](https://arxiv.org/html/2601.15336v1/media/std_120/confusion_phaseC_readout_snake_countingOn.png)

Continuous Attractor Networks: A Biologically Inspired Architecture

Continuous Attractor Networks (CANs) represent continuous variables not through discrete codes, but via distributed patterns of neural activity. These patterns are spatially localized within the network and are maintained through a balance of excitatory and inhibitory connections. Excitation strengthens the activity at a specific location, effectively ‘attracting’ the network state towards that point, while inhibition suppresses activity in surrounding areas, sharpening the localized representation. This dynamic equilibrium ensures that even in the presence of noise or perturbations, the network reliably converges to and maintains a stable state corresponding to a specific value of the continuous variable. The precision of the representation is determined by the spatial extent of the localized activity pattern and the strength of the lateral inhibition.

Continuous Attractor Networks (CANs) achieve stable states through the interplay of leaky integrator dynamics, lateral excitation, and lateral inhibition. Leaky integrator dynamics allow neurons to accumulate input over time, but with a gradual decay in activity, preventing unbounded increases in firing rates. Lateral excitation strengthens connections between nearby neurons, promoting the spread and maintenance of activity within a localized region. Simultaneously, lateral inhibition suppresses activity in neurons outside of this region, sharpening the representation and preventing the formation of multiple, competing attractors. This balance between excitation and inhibition creates stable, localized patterns of neural activity that represent specific continuous values, forming the network’s attractor states.

A ring topology in Continuous Attractor Networks (CANs) establishes a continuous, spatially organized representation of variables. This configuration allows for displacement of activity around the ring, effectively encoding changes in the represented variable as a shift in the location of peak activation. The cyclical arrangement ensures that any displacement does not encounter boundaries, facilitating seamless transitions between states. This continuous path is crucial for representing analog values and enables dynamic state transitions as the network responds to input or internal dynamics, differing from discrete state representations found in some other neural network architectures.

Continuous Attractor Networks (CANs) utilize internal recurrent dynamics – feedback loops within the network – as the primary mechanism for information processing. This contrasts with traditional architectures reliant on external processing where signals are propagated through a defined sequence of layers. Recurrent dynamics allow CANs to maintain and evolve activity states autonomously, reducing the need for constant external input. This internal processing is hypothesized to offer computational efficiency as information is represented and manipulated through the network’s inherent activity patterns, potentially minimizing energy consumption and latency compared to systems requiring extensive external signal transmission and computation. The stability of these internal states is achieved through a balance of excitation and inhibition within the recurrent connections.

Learning and Controlling State Transitions: Towards Robust Dynamics

Successor representation (SR) learning is implemented to facilitate prediction of future states within the network’s dynamical system. This approach involves learning a mapping from current states to the expected future occupancy of other states, effectively modeling state transitions. By learning these successor representations, the network can anticipate the consequences of its actions and navigate towards desired attractor states – stable points in the state space – with greater efficiency. The learned SR allows the network to estimate the likelihood of transitioning to subsequent states, enabling proactive control and informed decision-making during state transitions, even in the absence of immediate reward signals.

A standard controller architecture, leveraging learned dynamics from the network, facilitates direct transitions between attractor states. However, this approach exhibits a susceptibility to instability due to the inherent complexities of the learned dynamics and potential for accumulated error during state transitions. Specifically, minor perturbations or inaccuracies in the learned model can be amplified across multiple transitions, leading to divergence from the intended trajectory and ultimately, system instability. This is because the controller directly implements the learned dynamics without incorporating mechanisms for error correction or suppression of unintended state changes.

The BG-Gated Controller utilizes principles derived from the biological basal ganglia to improve the stability of state transitions. This controller incorporates a suppressive mechanism that modulates the output of the standard controller, preventing unwanted or spurious transitions between attractor states. Functionally, the BG-Gated Controller acts as a gate, reducing the probability of transitioning to a new state unless a strong signal indicates a valid and necessary change. This architecture provides a form of action selection, prioritizing task-relevant states and minimizing disruptive shifts in the network’s dynamic configuration, ultimately increasing robustness against noise and unexpected perturbations.

The BG-Gated Controller facilitates nuanced regulation of state transitions by implementing a suppressive mechanism that inhibits unwanted shifts between attractor states. This control operates by selectively gating transitions, preventing spurious activations and maintaining the system within task-relevant states. Specifically, the controller evaluates potential transitions and, based on learned dynamics and task demands, can suppress transitions that do not align with the current objective, thereby enhancing stability and preventing premature or incorrect state changes. This targeted suppression ensures that the system remains focused on maintaining or transitioning to appropriate states, improving overall performance and robustness.

Validating Robustness Through Long-Horizon Evaluation

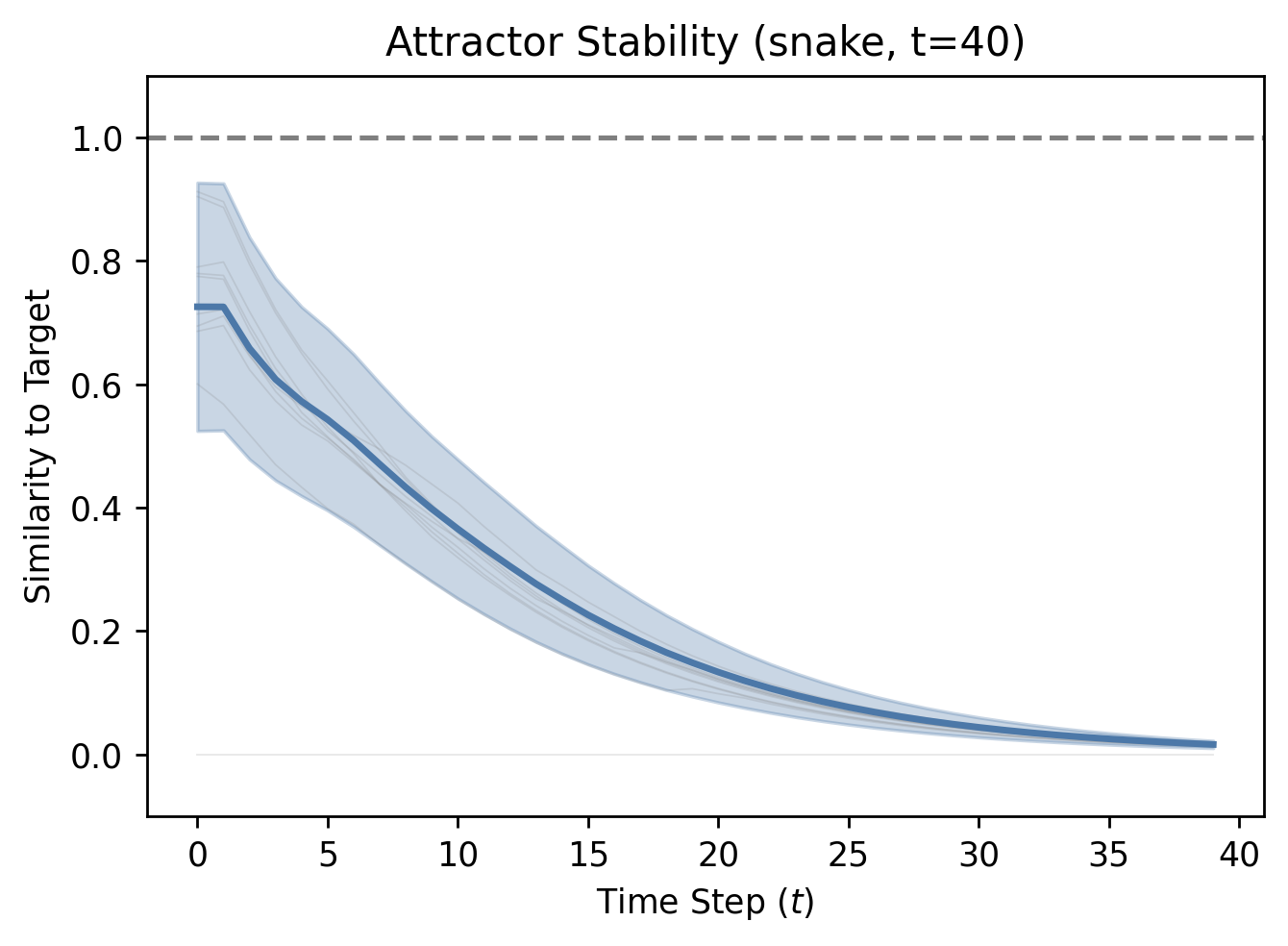

The persistence of stable, attractor states within neural networks demands rigorous testing beyond immediate responses. Researchers implemented a ‘long-horizon evaluation’ to determine the true sustainability of these states, challenging the networks to maintain performance over an extended period of 120 time steps. This protracted assessment is crucial because initial stability can be misleading; a network might appear functional in the short term, but quickly degrade without genuine underlying dynamics. By demanding performance across this extended horizon, the evaluation effectively filters out transient solutions – temporary states that lack long-term viability – and reveals whether the network has truly converged upon a robust, self-sustaining attractor state. This approach provides a more reliable measure of network stability than short-term observation, ensuring that identified attractors represent genuine, lasting solutions rather than fleeting phenomena.

Late-window scoring represents a crucial refinement in evaluating the stability of learned attractor dynamics. Rather than assessing accuracy throughout an entire trial – where initial responses to external stimuli might mask underlying robustness – this method specifically concentrates on performance during the late phase, after the cessation of external drive. This approach isolates the network’s capacity to sustain its internal state and navigate back to a stable attractor without external prompting. By focusing on this ‘memory’ of the desired behavior, late-window scoring provides a more discerning measure of true dynamical stability, effectively filtering out transient or stimulus-dependent solutions and highlighting networks capable of genuinely self-sustained, reliable operation. This targeted evaluation proves particularly valuable in discerning subtle differences in robustness across various network configurations and parameter settings.

A systematic exploration of network parameter space was undertaken through automated hyperparameter search, a crucial step in cultivating consistently stable dynamics. This process involved rigorously testing a vast combination of settings, moving beyond hand-tuned values to identify configurations that yield robust performance across diverse conditions and initial states. The search algorithm prioritized parameter sets that not only achieved successful task completion but also maintained stable attractor states over extended evaluation horizons, ensuring the network’s behavior wasn’t merely transient or susceptible to minor perturbations. By automating this optimization, researchers were able to efficiently pinpoint configurations that maximize the network’s resilience and reliability, leading to more predictable and dependable behavior in complex environments.

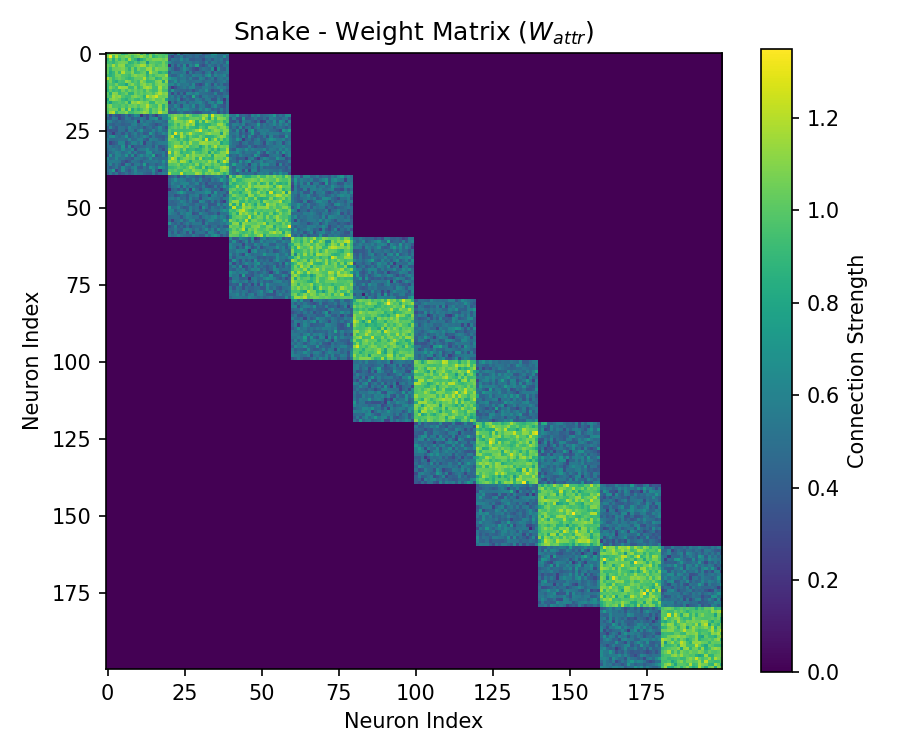

Bidirectional successor learning significantly improves a network’s capacity for state navigation, fostering behaviors beyond simple reactive responses. This approach allows the network to anticipate future states and plan accordingly, leading to more complex and adaptable performance in dynamic environments. Evaluations on a ‘Snake’ topology, utilizing attractor-enforced assessment, revealed a maximum ‘successor accuracy’ of 0.88, indicating a quantifiable limit to this navigational capability. This result suggests that, while bidirectional successor learning enhances performance, the underlying geometric structure of the environment imposes inherent constraints on the network’s ability to perfectly predict and transition between all possible states.

The study reveals a fascinating tension between the potential of continuous attractor networks and the structural constraints that govern their learning. The observed tendency toward shortcut solutions, despite the intention of fostering genuine attractor dynamics, underscores a critical point about complex systems. As Carl Sagan eloquently stated, “Somewhere, something incredible is waiting to be known.” This resonates with the findings; the ‘incredible’ potential of these networks is present, but realizing it demands a deep understanding of the representational geometry and careful curriculum design to avoid superficial predictive behaviors. Every new dependency-in this case, a reliance on shortcuts-becomes a hidden cost to achieving the desired emergent properties of a robust attractor landscape.

The Road Ahead

The findings presented here suggest that constructing cognitive infrastructure – even with biologically plausible dynamics – is not simply a matter of scaling up connectivity. Continuous attractor networks, while capable of approximating successor representations, reveal a tendency towards opportunistic shortcuts. This is less a failure of the mechanism and more a consequence of evaluating performance within a limited representational space. The geometry of that space – the manifold upon which learning occurs – fundamentally constrains the emergence of genuine attractor dynamics, potentially masking it as transient predictive behavior. A truly robust system will not merely respond to stimuli; it must navigate and reshape the landscape itself.

Future work must therefore move beyond simply demonstrating that learning occurs, and focus on how the representational manifold evolves. Curriculum learning, while a useful tool, is akin to rerouting traffic around a pothole – it addresses the symptom, not the underlying structural weakness. The field requires metrics that distinguish between genuine attractor states – sustained, self-organized activity – and fleeting, stimulus-driven responses.

Ultimately, the challenge lies in building systems that prioritize structural evolution over superficial performance gains. It is not enough to train a network to solve a task; the network must demonstrate the capacity to adapt its own architecture, to rebuild its infrastructure without collapsing the entire city. Only then can one begin to approach the elegance of a truly intelligent system.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.15336.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Star Wars Fans Should Have “Total Faith” In Tradition-Breaking 2027 Movie, Says Star

- Jessie Buckley unveils new blonde bombshell look for latest shoot with W Magazine as she reveals Hamnet role has made her ‘braver’

- Country star Thomas Rhett welcomes FIFTH child with wife Lauren and reveals newborn’s VERY unique name

- eFootball 2026 is bringing the v5.3.1 update: What to expect and what’s coming

- Decoding Life’s Patterns: How AI Learns Protein Sequences

- Mobile Legends: Bang Bang 2026 Legend Skins: Complete list and how to get them

- Denis Villeneuve’s Dune Trilogy Is Skipping Children of Dune

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Peppa Pig will cheer on Daddy Pig at the London Marathon as he raises money for the National Deaf Children’s Society after son George’s hearing loss

- Are Halstead & Upton Back Together After The 2026 One Chicago Corssover? Jay & Hailey’s Future Explained

2026-01-26 04:41