Author: Denis Avetisyan

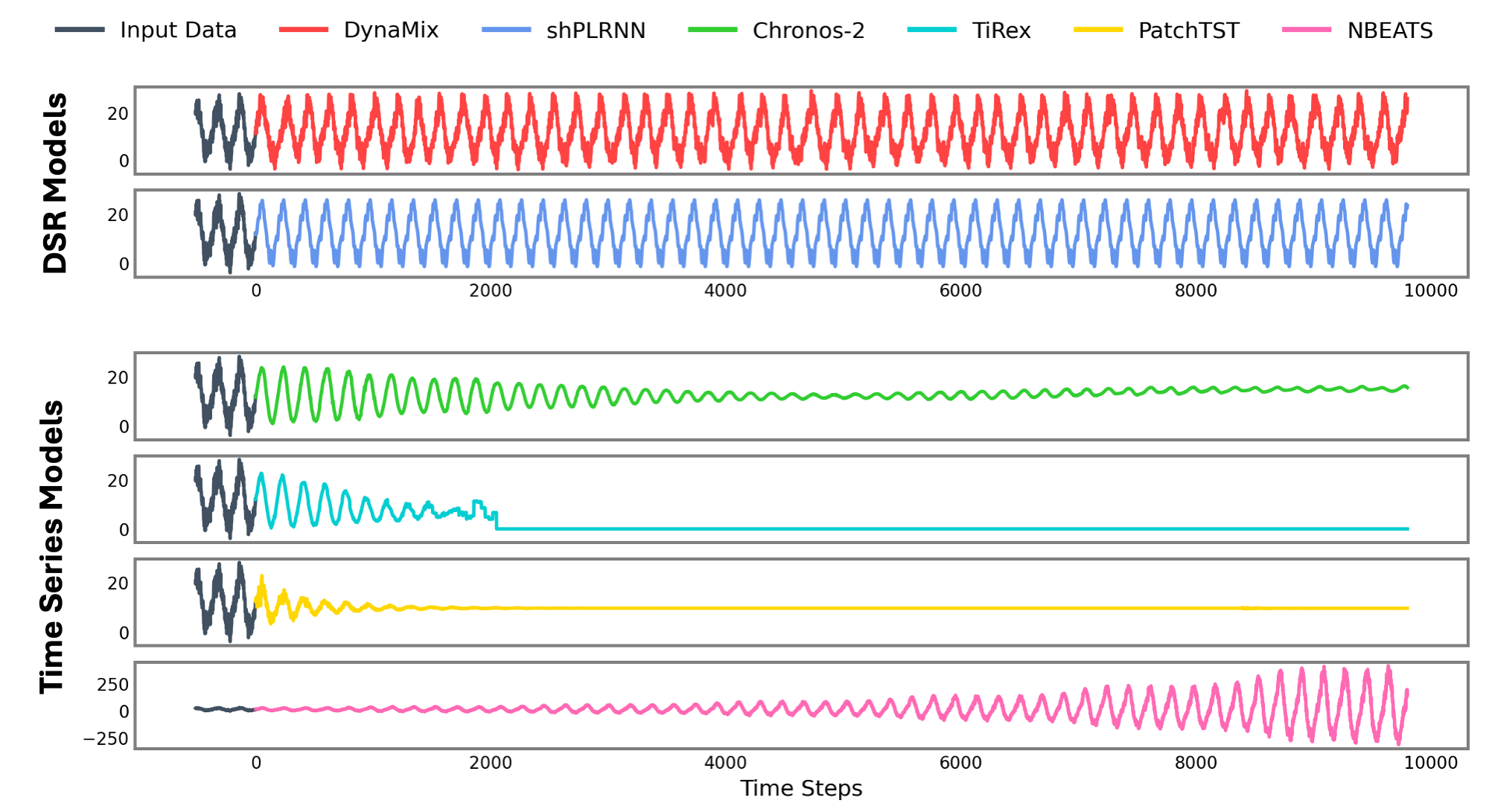

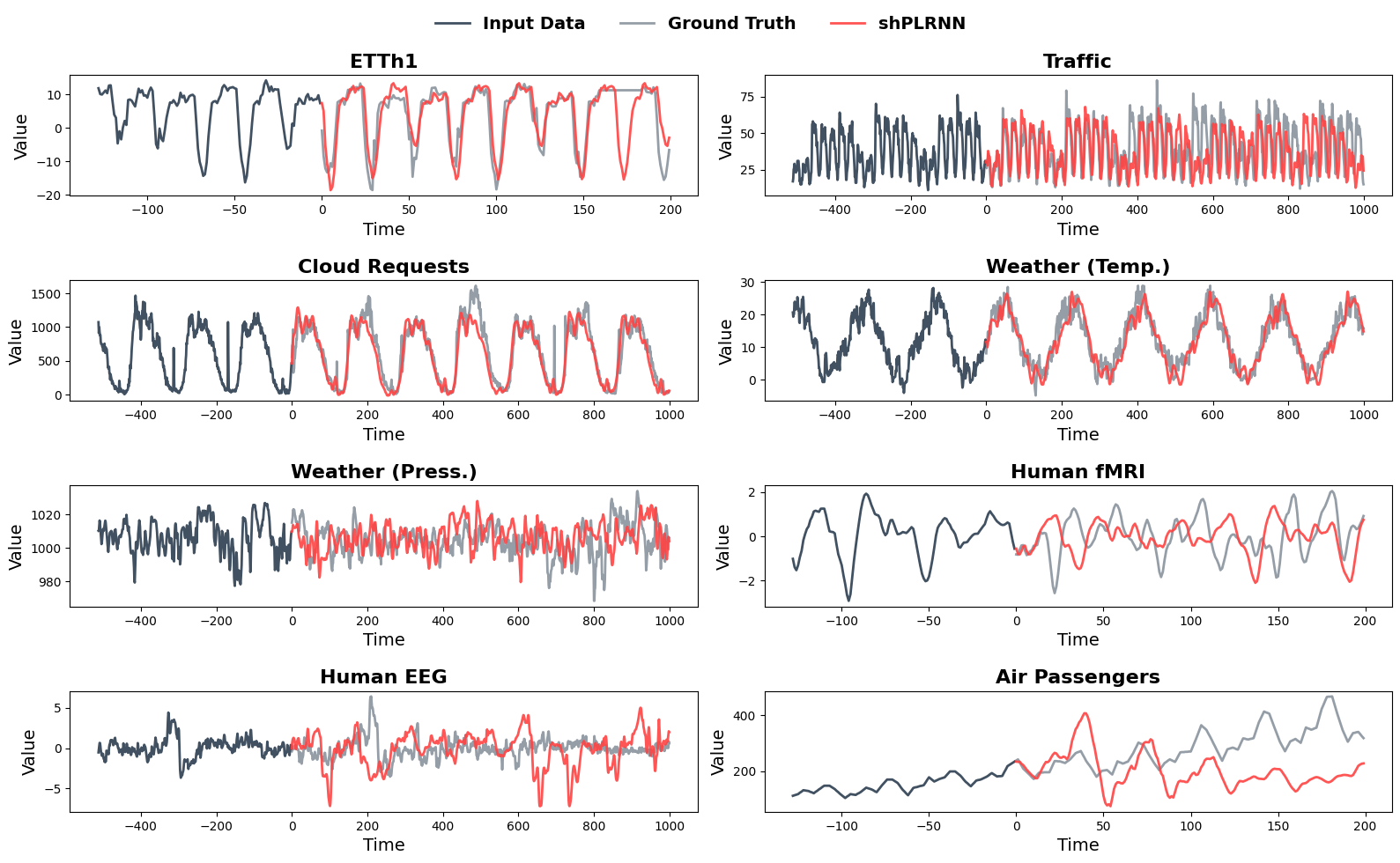

A new perspective on time series analysis argues that understanding the underlying system dynamics, rather than simply forecasting future values, is crucial for robust and generalizable models.

Integrating concepts from dynamical systems reconstruction and ergodic theory can improve long-term forecasting and reveal critical system behaviors like tipping points.

Despite recent advances in time series foundation models, a clear path toward truly robust and generalizable forecasting remains elusive. In the paper ‘Position: Why a Dynamical Systems Perspective is Needed to Advance Time Series Modeling’, we argue that integrating concepts from dynamical systems theory-particularly through techniques like dynamical systems reconstruction-offers a crucial pathway forward. This approach leverages the understanding that observed time series almost always originate from underlying dynamical systems, potentially enabling not only improved short-term predictions but also insights into long-term statistical behavior and system tipping points. Can a deeper embrace of dynamical systems principles unlock the next generation of time series models with enhanced performance and reduced computational demands?

Navigating the Currents of Change

The world is replete with systems that aren’t static, but rather continuously change over time – these are best characterized as dynamical systems. From the swirling complexity of weather patterns and the fluctuating values of financial markets to the rhythmic beating of a heart or the growth of a population, these systems evolve according to underlying rules and are sensitive to external influences. These rules, whether expressed as physical laws, economic principles, or biological processes, dictate how the system’s state changes, but often, even with precise knowledge of these rules, predicting long-term behavior proves remarkably difficult. The challenge lies in the inherent interconnectedness and feedback loops within these systems, where a small change in initial conditions can lead to drastically different outcomes – a hallmark of what is known as ‘chaos’. Understanding these systems therefore requires a shift from seeking simple, linear explanations to embracing the complexity and inherent unpredictability of dynamic processes.

Attractors represent the long-term behavior of a dynamical system, serving as a kind of magnetic pull towards specific states despite potentially complex and fluctuating conditions. These aren’t necessarily single points of stability; rather, attractors can take the form of stable cycles or, more interestingly, intricate patterns known as strange attractors. The dimensionality of these strange attractors is often non-integer, a property described as a fractal dimension, signifying their self-similar structure across different scales. This fractal nature implies that the system’s behavior is not simply repeating, but rather explores a complex, infinitely detailed space, hinting at an underlying order within apparent chaos and allowing scientists to characterize the complexity of the system itself. Understanding the nature of an attractor-its form and dimensionality-provides crucial insight into the system’s overall dynamics and predictability.

Reconstructing the subtle geometry of attractors – the ‘fingerprints’ of a dynamical system’s behavior – is profoundly difficult when relying on incomplete or noisy observational data. This limitation stems from the inherent sensitivity of these systems, especially those exhibiting chaos, where even minuscule errors in initial conditions rapidly amplify due to positive Lyapunov exponents [latex] (>0) [/latex]. These exponents quantify the rate at which nearby trajectories diverge, effectively establishing a horizon beyond which long-term prediction becomes impossible. Consequently, while the underlying deterministic rules might be known, practical forecasting and control are severely restricted, necessitating probabilistic approaches and an acceptance of inherent unpredictability in complex systems. The challenge isn’t simply one of increased computational power, but rather a fundamental limit imposed by the dynamics themselves, demanding innovative techniques for state estimation and uncertainty quantification.

The Precipice of Instability

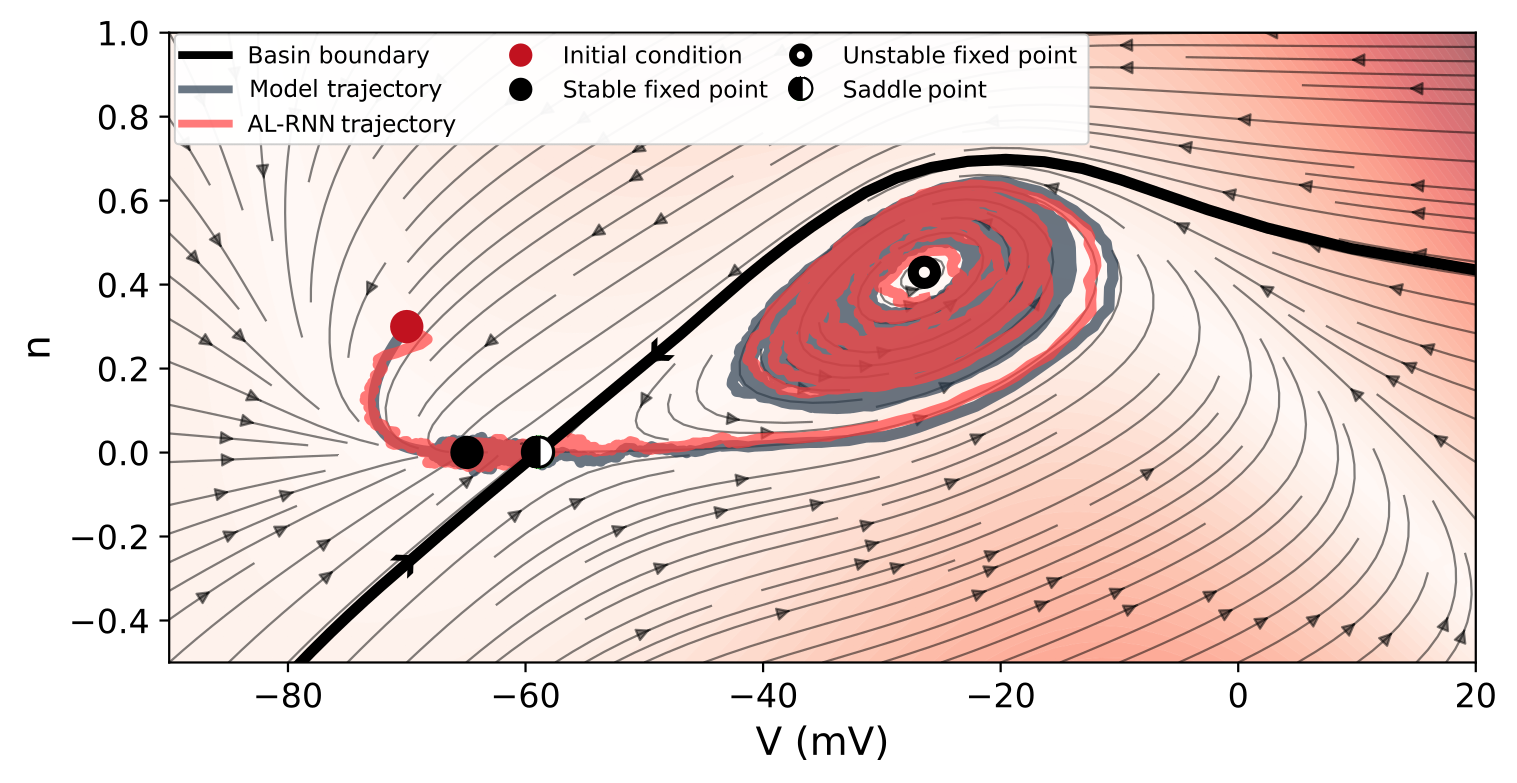

Tipping points in dynamical systems describe instances where a gradual alteration of control parameters leads to a sudden, qualitative change in system behavior. These shifts are not proportional to the initial slow changes; rather, they occur when a specific threshold is surpassed, resulting in a rapid transition to a new stable state. This threshold represents a critical value beyond which the system’s inherent resistance to change is overcome. The accumulated slow changes effectively load the system until this point, after which even small additional changes can trigger a disproportionately large response. Consequently, predicting tipping points requires identifying these thresholds and understanding the mechanisms by which slow changes interact with the system’s dynamics to initiate abrupt shifts.

Tipping points are not singular events but can arise from distinct dynamical processes. Bifurcation-induced tipping points occur as a system’s parameters change, altering the stability of fixed points or limit cycles and leading to a qualitative shift in the system’s long-term behavior – effectively changing the ‘attractor’ towards which the system evolves. Alternatively, rate-induced tipping points result from exceeding a critical rate of change in external forcing, where the system is unable to maintain its current state despite the forcing being within its overall capacity. These are distinct from bifurcations, as the system can theoretically accommodate the forcing at a slower rate. Both mechanisms represent shifts in system behavior driven by internal dynamics or external inputs, respectively, and contribute to the broader phenomenon of system instability at tipping points.

Distinguishing between bifurcation-induced (B-Tipping), rate-induced (R-Tipping), and noise-induced (N-Tipping) mechanisms is essential for predictive modeling of system instability. B-Tipping occurs when a gradual parameter change alters the qualitative structure of a system’s attractor, leading to a sudden shift in behavior. R-Tipping results from exceeding a critical rate of change in input parameters, overwhelming the system’s capacity to maintain its current state. N-Tipping, conversely, is triggered by random fluctuations exceeding a certain amplitude, pushing the system out of its stable basin of attraction. Accurate identification of the dominant tipping mechanism allows for targeted intervention strategies; for example, slowing the rate of change may prevent R-Tipping, while increasing system robustness can mitigate N-Tipping, and understanding bifurcation points allows for proactive management of B-Tipping risks.

Reconstructing the Hidden Order

State estimation is the process of determining the internal condition, or ‘state’, of a dynamic system based on a series of observations. This inference is inherently complex due to the presence of noise within the data acquisition process and the frequent unavailability of complete information regarding all relevant variables. The system’s true state is typically unknown and must be estimated statistically, often employing techniques that minimize the discrepancy between predicted and observed outputs. The accuracy of state estimation is directly impacted by the quality and quantity of the observed data, as well as the sophistication of the chosen estimation algorithm; errors in state estimation can propagate and significantly affect predictions of future system behavior.

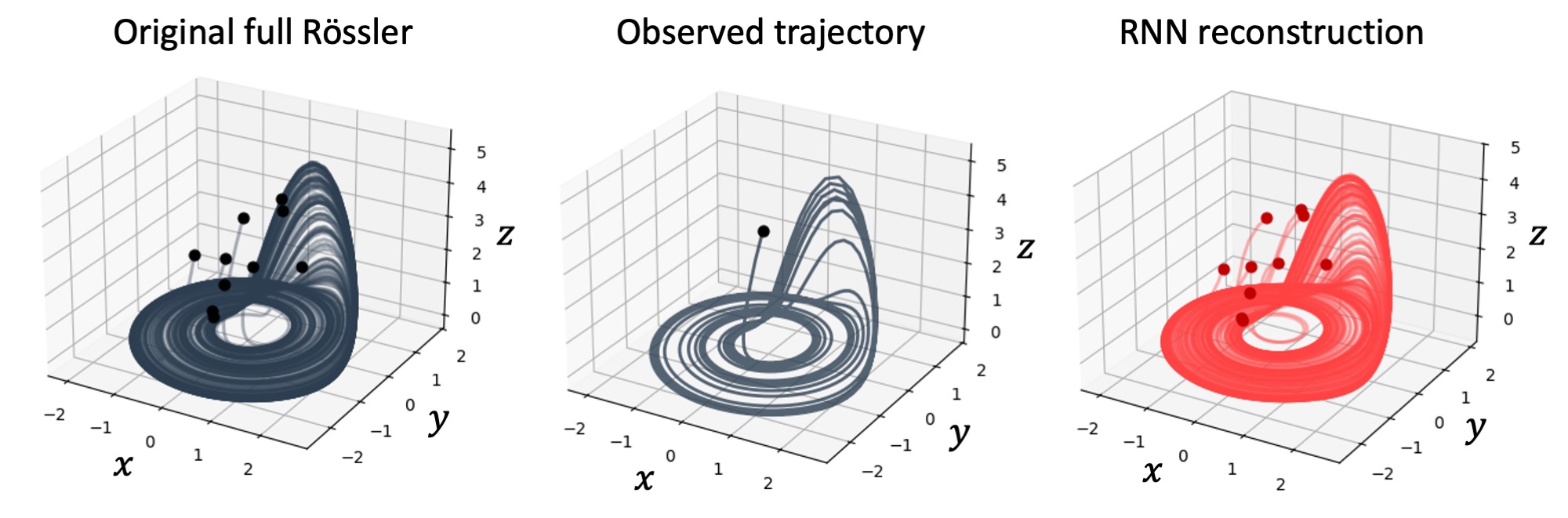

Delay embedding, a technique used in nonlinear time series analysis, allows for the reconstruction of the system’s attractor – a geometric representation of the system’s long-term behavior – from a single observed variable. This is achieved by creating a series of delayed coordinates, essentially treating each point in time as a separate dimension in a higher-dimensional space. Specifically, a new vector is formed at each time step using values of the single time series at various time delays τ. The choice of the appropriate time delay and embedding dimension is critical for accurate reconstruction; insufficient delay fails to capture the system’s dynamics, while excessive delay introduces redundancy. The reconstructed attractor, while an approximation, provides a surrogate model enabling analysis of the system’s characteristics, such as dimensionality and stability, without requiring direct measurement of multiple state variables.

Multiple shooting is an iterative optimization technique used in state estimation to enhance accuracy, particularly when dealing with nonlinear dynamical systems. The method operates by dividing the state estimation problem into a series of shorter intervals, or ‘shooting intervals.’ Within each interval, an initial guess for the system’s state is used to propagate the solution forward in time. Crucially, continuity is then enforced at the boundaries between these intervals by minimizing the difference between the predicted state at the end of one interval and the initial state of the subsequent interval. This process creates a system of equations that, when solved, yields a more accurate estimate of the system’s trajectory than single-interval methods, as it effectively addresses the accumulation of error over longer time scales.

Refining Our Predictive Capabilities

State estimation, a critical process in fields ranging from robotics to weather forecasting, historically demands substantial computational resources and often struggles with inaccuracies stemming from noisy data. Traditional methods, while effective in controlled environments, can become prohibitive as system complexity increases or data quality diminishes. Consequently, researchers are actively investigating alternative training paradigms to overcome these limitations. These advancements focus on improving both the speed and resilience of state estimation algorithms, moving beyond reliance on exhaustive computations and embracing techniques that better filter out disruptive noise. The goal is to create systems capable of accurately reconstructing a system’s internal state even when faced with imperfect or incomplete information, paving the way for more efficient and reliable applications in dynamic, real-world scenarios.

State estimation, the process of determining a system’s hidden variables from incomplete or noisy data, often relies on machine learning models that require extensive training. A key innovation to accelerate this learning is ‘teacher forcing’, a technique where the model is initially guided by providing the correct, or ‘teacher’, output during training, rather than relying solely on its own previous predictions. Variants of this approach, such as ‘sparse teacher forcing’, strategically reduce the frequency of this guidance, encouraging the model to learn more independently, while ‘generalized teacher forcing’ dynamically adjusts the level of guidance based on the model’s confidence. These methods effectively balance exploration and exploitation, allowing models to converge faster and achieve improved accuracy in reconstructing complex system dynamics, ultimately leading to more reliable and efficient state estimation.

State estimation, crucial for understanding evolving systems, often relies on models prone to error and computational strain. Recent innovations address this by strategically combining external guidance with the model’s own predictions. This blended approach doesn’t simply dictate the ‘correct’ answer, but rather uses accurate data to nudge the model towards more reliable inferences, particularly during initial learning phases. The system learns to balance reliance on established truths with its own evolving understanding of the underlying dynamics, resulting in a more robust and efficient reconstruction of the system’s state. This careful calibration minimizes the impact of noisy data and computational limitations, allowing for more accurate and timely estimations even in complex or uncertain environments.

Beyond Prediction: A Future of Informed Intervention

Accurate reconstruction of a system’s attractor – the set of states toward which its dynamics evolve – and the prediction of associated tipping points represent a paradigm shift in managing complex systems. This capability extends far beyond theoretical understanding, offering practical tools for intervention and mitigation across diverse fields. For instance, in climate science, identifying attractors allows researchers to anticipate abrupt shifts in weather patterns or ocean currents, enabling proactive disaster preparedness. Similarly, in financial markets, recognizing early warning signs of instability could prevent cascading failures and systemic risk. Beyond these examples, the ability to forecast critical transitions has applications in epidemiology, ecology, and even social systems, offering the potential to move from reactive crisis management to proactive, preventative strategies that enhance resilience and stability.

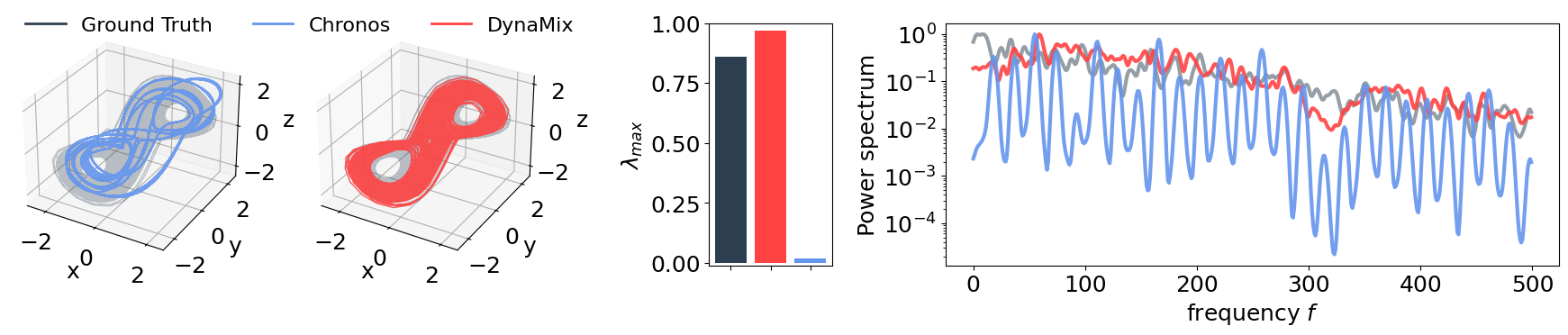

The Lorenz-63 model, a deceptively simple system of equations originally devised as an analogue for atmospheric convection, provides a crucial proving ground for advanced forecasting techniques. Though a significant simplification of real-world weather, the model reliably exhibits chaotic behavior – sensitive dependence on initial conditions – mirroring the unpredictability inherent in meteorological systems. Researchers leverage the Lorenz-63 model to test and refine methods for attractor reconstruction and tipping point detection, effectively ‘training’ algorithms to identify subtle precursors to dramatic shifts in state. Successful application to this established chaotic system bolsters confidence in the potential for these techniques to ultimately improve the accuracy of longer-term weather prediction and, crucially, to anticipate extreme events before they unfold.

Current methodologies for comparing complex system models prioritize achieving identical frequency content, a concordance quantified by a Hellinger Distance of zero. This focus ensures that modeled oscillations and periodic behaviors align with observed data, providing confidence in short-term predictions. However, researchers recognize limitations in this approach, particularly when assessing long-term dynamics; the Hellinger Distance proves insensitive to subtle shifts in the timing of events. Consequently, investigations are now centering on the Wasserstein Distance, a metric better equipped to capture discrepancies in temporal structure and predict how systems evolve over extended periods. This shift promises more robust assessments of model accuracy and improved forecasting capabilities for complex phenomena, extending beyond simple frequency matching to encompass the entire temporal landscape of a system’s behavior.

![Even minimal noise ([latex]1\%[/latex]) causes rapid divergence in trajectories from the Lorenz-63 system, rendering long-term prediction impossible beyond approximately one Lyapunov time, a phenomenon exacerbated by increased noise levels ([latex]10\%[/latex]).](https://arxiv.org/html/2602.16864v1/Figures/chaos_ts.png)

The pursuit of improved time series forecasting, as detailed in the article, often introduces layers of complexity that obscure fundamental principles. The work rightly emphasizes the need to move beyond purely statistical approaches and embrace the underlying dynamical systems governing the data. This aligns with a core tenet of clear thinking – stripping away unnecessary complication to reveal the essential structure. As Ada Lovelace observed, “The Analytical Engine has no pretensions whatever to originate anything. It can do whatever we know how to order it to perform.” This sentiment resonates deeply; models, like the Analytical Engine, are only as insightful as the understanding of the system-the underlying dynamics-they embody. Focusing on attractor reconstruction and ergodic theory isn’t about adding complexity, but rather about precisely defining what the model should do, and ensuring it reflects the true system behavior.

Future Trajectories

The persistent struggle within time series modeling remains not merely prediction, but generalization – the ability to extrapolate beyond the immediately observed. Current methodologies often treat data as a static property, obscuring the generative process. This work proposes a shift: viewing time series not as patterns to be modeled, but as the fleeting shadows of underlying dynamical systems. The utility of Dynamical Systems Reconstruction, therefore, is not in providing another forecasting algorithm, but in forcing a confrontation with the system’s intrinsic dimensionality and inherent limitations of predictability.

Critical to future work is a rigorous assessment of the computational cost associated with DSR, particularly as applied to high-dimensional data. The pursuit of efficiency cannot, however, justify a return to purely parametric models, which, by definition, discard information. Instead, the focus should be on developing sparse reconstruction techniques and exploiting the inherent symmetries within dynamical systems. Ergodic theory, while theoretically potent, requires practical implementations that are robust to noise and non-stationarity.

Ultimately, the integration of dynamical systems theory with recurrent neural networks is not a synthesis, but a necessary correction. The former provides the conceptual framework; the latter, the computational engine. The true measure of progress will not be incremental improvements in forecast accuracy, but a demonstrable increase in understanding – a move from predicting what will happen, to explaining why. Unnecessary complexity remains violence against attention; clarity, the ultimate metric.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.16864.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- CookieRun: Kingdom 5th Anniversary Finale update brings Episode 15, Sugar Swan Cookie, mini-game, Legendary costumes, and more

- Call the Midwife season 16 is confirmed – but what happens next, after that end-of-an-era finale?

- Taimanin Squad coupon codes and how to use them (March 2026)

- Robots That React: Teaching Machines to Hear and Act

- Heeseung is leaving Enhypen to go solo. K-pop group will continue with six members

- Gold Rate Forecast

- PUBG Mobile collaborates with Apollo Automobil to bring its Hypercars this March 2026

- Alan Ritchson’s ‘War Machine’ Netflix Thriller Breaks Military Action Norms

- Marilyn Manson walks the runway during Enfants Riches Paris Fashion Week show after judge reopened sexual assault case against him

- How to get the new MLBB hero Marcel for free in Mobile Legends

2026-02-21 13:47