Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research challenges the notion that hypergraphs offer a fundamentally richer framework for modeling complex systems than standard graphs.

The paper demonstrates that apparent advantages of hypergraphs often arise from conflating multivariate interactions with the underlying network structure itself.

A prevailing view in network science posits that standard graphs are limited to representing pairwise interactions, necessitating hypergraphs to capture higher-order dependencies. However, in ‘Graphs are maximally expressive for higher-order interactions’, we demonstrate that graph-based models are, in fact, fully capable of representing such interactions, and that hypergraphs represent a constrained subset of graph representations. This challenges the notion of unique phenomena arising solely from hypergraph structures, showing that effects often attributed to higher-order connectivity can be recovered within standard graph frameworks. Consequently, does this recast the role of hypergraphs, suggesting their utility lies not in expanding representational power, but in providing specific parameterizations of multivariate interactions?

Beyond Pairwise Thinking: The Limits of Simple Networks

The simplification of complex systems into pairwise interactions, while computationally convenient, often fails to capture the nuances of real-world phenomena. Many processes, from the spread of information through social networks to the collective behavior of cells, involve interactions among groups, or are influenced by systemic factors beyond simple connections between two entities. Traditional graph models, built upon the foundation of nodes and edges representing these pairwise relationships, struggle to represent these higher-order interactions – those involving three or more nodes simultaneously. This limitation impacts the accuracy of predictions and hinders a complete understanding of emergent behaviors; for example, the effectiveness of a marketing campaign isn’t solely determined by who influences whom, but also by the strength of influence within communities. Consequently, researchers are increasingly recognizing the need for more sophisticated frameworks that move beyond the constraints of dyadic relationships to accurately model and analyze these multifaceted systems.

The conventional representation of networks through an [latex]Adjacency Matrix[/latex] fundamentally limits the modeling of intricate group interactions. This matrix, designed to denote connections between pairs of nodes, inherently struggles with scenarios where effects propagate through groups, or depend on the collective state of multiple interconnected entities. While effective for depicting one-to-one relationships, it fails to capture the nuances of multi-node dependencies common in phenomena like collective decision-making, coordinated movements, or the spread of information within tightly-knit communities. Consequently, analyses based solely on this pairwise representation often provide an incomplete, and potentially misleading, picture of complex systemic behaviors, necessitating the development of more sophisticated network formalisms capable of representing higher-order interactions.

Understanding the spread of contagion, be it disease, information, or behavioral trends, often necessitates moving beyond analyses focused solely on direct, pairwise interactions. Traditional network models, while useful for illustrating basic transmission, frequently fail to capture the nuanced reality of group effects, where the influence of multiple individuals collectively shapes outcomes. Complex social behaviors, such as collective decision-making or the formation of norms, are rarely determined by simple one-on-one exchanges; instead, they emerge from the intricate interplay within groups. Consequently, researchers are increasingly turning to tools like hypergraphs and simplicial complexes – mathematical frameworks capable of representing interactions involving any number of nodes – to more accurately model these higher-order relationships and gain a more complete understanding of dynamic processes in social and biological systems.

![Node interactions are determined by functions defined on adjacency sets-which constrain influence-rather than by the adjacencies themselves, as illustrated by this example of a proof-of-concept ODE system [latex]Eq.4[/latex] where functions connect encircled nodes (blue and red).](https://arxiv.org/html/2602.16937v1/x1.png)

Beyond Pairs: Modeling Complexity with Higher-Order Networks

Higher-order networks extend the capabilities of traditional graph theory by moving beyond pairwise relationships to explicitly model interactions involving any number of nodes. Conventional graphs represent connections between two entities; however, many real-world phenomena involve collective interactions – for example, a research paper with multiple authors, a protein complex comprised of several proteins, or a social group conversation. Higher-order networks, utilizing structures like hypergraphs, directly represent these [latex]n[/latex]-ary relationships as hyperedges connecting sets of nodes. This allows for a more accurate and comprehensive representation of system structure where group dynamics and multivariate dependencies are critical, providing a framework to analyze patterns and processes that are not readily captured by simple pairwise connections.

Hypergraphs extend the traditional graph model by allowing edges, known as hyperedges, to connect an arbitrary number of nodes. In standard graphs, an edge always connects exactly two nodes; hypergraphs remove this restriction, permitting connections between any sized subset of nodes. This capability is crucial for modeling [latex]Multivariate Interaction[/latex], where relationships are not dyadic but involve multiple entities simultaneously. For example, a research paper might have multiple authors (nodes) connected by a hyperedge representing co-authorship, or a chemical reaction might involve multiple reactants (nodes) connected by a hyperedge representing the reaction event. The formal definition of a hypergraph consists of a set of nodes [latex]V[/latex] and a set of hyperedges [latex]E[/latex], where each hyperedge [latex]e \in E[/latex] is a subset of [latex]V[/latex].

Traditional network representation relies on the adjacency matrix to define pairwise relationships between nodes; however, higher-order networks require a generalization of this structure. The [latex]Adjacency\,Tensor[/latex] serves as this generalization, accommodating edges that connect any number of nodes, thereby capturing multivariate interactions. While the adjacency tensor allows for a more complete representation of complex relationships, this work establishes that hypergraph models built upon these tensors do not fundamentally exceed the expressive capabilities of models based on traditional graphs and adjacency matrices; any pattern representable with a hypergraph can also be represented, albeit potentially with increased complexity, using a standard graph-based approach.

![While hypergraph parametrizations, exemplified in panel (a) by consistent hyperedges satisfying [latex] ext{Eq. 19}[/latex], are a specific case of graph-based models, panel (b) demonstrates that models with multivariate coupling functions, even those mirroring the form of [latex] ext{Eq. 20}[/latex], cannot be represented by hypergraphs due to inconsistent shared memberships, highlighting the arbitrariness of labeling such models as solely 'higher-order' or 'pairwise'.](https://arxiv.org/html/2602.16937v1/x5.png)

Analytical Tools: Dissecting Complex Network Behavior

Mean-Field Calculation is an analytical technique used to approximate the behavior of complex networks by focusing on the average effect of interactions between nodes. Instead of modeling each node and its connections individually, this method simplifies the system by assuming each node experiences an average, or ‘mean’, field generated by all other nodes. This allows for the derivation of self-consistent equations describing the collective dynamics of the network, reducing computational complexity while retaining key insights into system-level properties. The technique is particularly useful when dealing with large networks where tracking individual node interactions is computationally intractable, and it provides a framework for understanding phenomena like phase transitions and emergent behavior. [latex] \hat{H}_i = \sum_{j \neq i} J_{ij} s_i s_j [/latex] represents a simplified Hamiltonian often used in mean-field approximations of spin glasses, where [latex] s_i [/latex] denotes the state of node i and [latex] J_{ij} [/latex] represents the interaction strength between nodes i and j.

Mean-field calculation simplifies the analysis of complex networks by replacing the detailed interactions between individual nodes with an average effect. Instead of tracking the state of each node independently, this technique models the influence of all other nodes as a single, collective contribution. This aggregated influence is then used to derive equations describing the average behavior of the network, allowing for the prediction of emergent properties and collective dynamics. The accuracy of this approximation depends on the degree of homogeneity within the network and the assumption that individual node responses are representative of the overall population. [latex] \frac{d\langle x \rangle}{dt} = f(\langle x \rangle) [/latex] represents a simplified dynamic, where [latex] \langle x \rangle [/latex] is the average state of the network and f() represents the averaged interaction function.

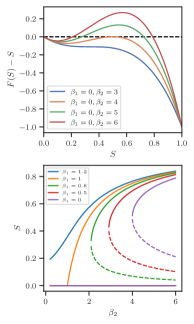

Equilibrium models in complex networks define stable states where the system’s overall behavior does not change over time; these are determined by balancing forces represented by the interactions between nodes and the individual [latex]f(x)[/latex] function defining each node’s behavior – its ‘Node Function’. Synchronization, a specific type of coordinated behavior, occurs when nodes adjust their states to match each other, either in frequency or phase. The propensity for synchronization is directly related to network topology and the characteristics of the Node Function, with variations in these factors influencing the stability and type of synchronized patterns observed. Analysis of these models allows prediction of the network’s response to perturbations and identification of critical parameters that govern transitions between stable states and synchronized behavior.

Spectral theory, when applied to network analysis, utilizes the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of a network’s adjacency or Laplacian matrix to reveal inherent structural properties. The spectrum – the set of eigenvalues – provides information regarding network characteristics such as connectivity, clustering, and the presence of communities. Specifically, the magnitude of eigenvalues indicates the strength of corresponding eigenvectors, which represent dominant modes of network behavior. Analyzing the distribution of eigenvalues, often visualized in a spectrum plot, can identify the number of connected components, detect the presence of bottlenecks, and even predict network robustness to node failures. λ represents an eigenvalue, and its associated eigenvector [latex] v [/latex] defines a mode of oscillation or influence within the network, with larger eigenvalues corresponding to more significant modes.

Beyond the Pair: Applications and a Realistic Outlook

The applicability of higher-order networks extends far beyond traditional pairwise interactions, offering a powerful framework for analyzing systems across diverse scientific disciplines. In social science, these networks can model group dynamics and collective behavior, moving beyond simple dyadic relationships to capture the influence of entire communities. Neuroscience benefits from this approach by enabling the study of neural interactions beyond single synapses, revealing how ensembles of neurons collaborate to process information. Even in materials science, higher-order networks provide insights into complex material properties, examining how multiple atoms or molecules interact to determine a material’s overall characteristics. This broadened perspective acknowledges that real-world interactions are rarely limited to pairs, and instead often involve intricate, collective relationships that demand a more sophisticated analytical approach.

Bipartite graphs and multilayer networks represent powerful adaptations of traditional network analysis, extending its utility to increasingly complex systems. Bipartite structures excel at modeling relationships between two disparate types of entities – consider, for example, the connections between researchers and their publications, or patients and the medications they receive. These graphs, rather than focusing on connections within a single group, highlight the interactions across groups. Simultaneously, multilayer networks move beyond simple, single-layer representations by acknowledging that interactions often occur across multiple, interconnected layers of organization. A social network, for instance, might be modeled with layers representing online interactions, familial ties, and professional collaborations, allowing researchers to analyze how influence propagates not just within a network, but between these distinct spheres of connection.

Inferring the hidden architecture of complex systems relies increasingly on network reconstruction techniques, which attempt to map underlying relationships from limited observational data. This process isn’t simply about identifying connections; it aims to reveal irreducible interactions – those essential links that cannot be explained by simpler, indirect pathways. Sophisticated algorithms are employed to disentangle direct and indirect effects, building a network that accurately reflects the system’s core dependencies. The success of these reconstructions hinges on the ability to handle noisy data and incomplete information, but the resulting networks provide a powerful tool for understanding system behavior and predicting responses to external stimuli, offering insights previously obscured by the system’s complexity.

The recent progress in higher-order network analysis offers significant potential for unraveling the intricacies of complex systems and designing targeted interventions, yet it’s crucial to recognize its evolutionary relationship to established graph-based modeling. While these advancements introduce tools for capturing interactions beyond simple pairwise connections, the fundamental principles remain rooted in graph theory; it refines existing frameworks rather than overturning them. This means the power lies in a more nuanced representation of relationships, allowing researchers to identify subtle patterns and dependencies previously obscured by simpler models, ultimately leading to more informed strategies in fields ranging from public health to materials science, but building upon, rather than replacing, the foundations of network analysis.

[/latex]-but multilayer graph representations restore a one-to-one correspondence between hypergraph cliques and graph cliques by enforcing monochromatic clique composition.](https://arxiv.org/html/2602.16937v1/x8.png)

The pursuit of fundamentally ‘new’ network frameworks often overlooks a simple truth: elegance doesn’t guarantee robustness. This paper dismantles the notion that hypergraphs inherently possess capabilities beyond standard graphs, revealing how perceived complexity arises from misinterpreting multivariate interactions. It’s a familiar cycle; a theoretical leap celebrated, then slowly eroded by the realities of implementation. As Grigori Perelman once stated, “It is better to remain silent and be thought a fool than to speak and remove all doubt.” The claim that hypergraphs unlock unique phenomena feels optimistic, given the tendency for production systems to expose the limitations of even the most promising theories. The insistence on finding something fundamentally different echoes the endless search for a ‘silver bullet’ in systems design – a search destined to repeat itself as each ‘revolutionary’ framework inevitably becomes tomorrow’s tech debt.

So, What Breaks Next?

The insistence on novelty in network science remains… predictable. This work suggests much of what is hailed as ‘higher-order’ interaction is simply multivariate correlation wearing a fancier hat. The field will, naturally, ignore this and continue building hypergraph-flavored tools, because ‘scalable’ rarely survives contact with actual data. It is a reasonable expectation that, given sufficient computational resources and enough contrived datasets, someone will find a problem where a hypergraph solution is marginally faster than a well-optimized graph algorithm. This will be presented as a breakthrough.

The real challenge isn’t whether hypergraphs can model something graphs cannot, but whether the added complexity is ever justified. The tendency to conflate mathematical generality with practical utility is a recurring error. The focus should shift from simply representing interactions to understanding the limitations of any representation – particularly regarding interpretability and robustness.

Perhaps the most honest outcome of this line of inquiry will be a quiet return to simpler models. Better one monolith, painstakingly validated, than a hundred lying microservices, each claiming to capture some elusive ‘higher-order’ effect. The logs, as always, will be the final arbiter.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.16937.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- CookieRun: Kingdom 5th Anniversary Finale update brings Episode 15, Sugar Swan Cookie, mini-game, Legendary costumes, and more

- Call the Midwife season 16 is confirmed – but what happens next, after that end-of-an-era finale?

- Taimanin Squad coupon codes and how to use them (March 2026)

- Robots That React: Teaching Machines to Hear and Act

- Heeseung is leaving Enhypen to go solo. K-pop group will continue with six members

- Gold Rate Forecast

- PUBG Mobile collaborates with Apollo Automobil to bring its Hypercars this March 2026

- Alan Ritchson’s ‘War Machine’ Netflix Thriller Breaks Military Action Norms

- Marilyn Manson walks the runway during Enfants Riches Paris Fashion Week show after judge reopened sexual assault case against him

- How to get the new MLBB hero Marcel for free in Mobile Legends

2026-02-21 22:04