Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research reveals that artificial intelligence agents consistently demonstrate overconfidence when predicting their success at coding tasks, raising critical questions about their reliability and safe deployment.

This study quantifies agentic uncertainty in large language models performing coding benchmarks like SWE-bench, highlighting a significant calibration gap and the need for improved self-assessment mechanisms.

Despite increasing reliance on autonomous agents, their ability to accurately predict their own success remains largely unknown. This is the central question addressed in ‘Agentic Uncertainty Reveals Agentic Overconfidence’, which investigates how large language models estimate their likelihood of success on coding tasks. The study demonstrates a systematic tendency toward overconfidence, with agents frequently predicting high success rates despite comparatively low actual performance. Given these findings, how can we develop more reliable self-assessment mechanisms for AI agents and mitigate the risks associated with unchecked automation?

The Illusion of Confidence: Decoding Agent Uncertainty

The growing reliance on large language models for tasks like code generation and automated repair presents a significant challenge in evaluating their true capabilities. Current performance metrics often focus solely on whether the generated code functions correctly, neglecting to quantify the model’s own assessment of its solution’s reliability. This omission creates a potential blind spot, as a model might produce working code with minimal confidence, or conversely, reject a perfectly valid solution due to internal uncertainty. Without a robust understanding of an LLM’s self-assessment, developers are left with a performance score devoid of crucial context, increasing the risk of deploying subtly flawed or fragile code under the guise of successful automation. The ability to discern how sure a model is about its answer is therefore paramount for safe and effective integration into real-world programming workflows.

The practical deployment of code generated by large language models faces a significant hurdle: a lack of reliable indicators of solution correctness. Without a quantifiable understanding of an agent’s confidence – or lack thereof – developers may unknowingly integrate flawed code into larger systems, operating under the potentially dangerous assumption of a functioning solution. This creates a false sense of security, as superficially plausible code can harbor subtle errors that only manifest under specific conditions or with prolonged use. Consequently, the adoption of AI-assisted programming tools is hampered, as developers rightly hesitate to trust outputs without a clear understanding of their inherent reliability and potential for failure, ultimately slowing the integration of these powerful tools into real-world applications.

The reliable deployment of AI-assisted programming tools hinges on a critical, yet often overlooked, component: quantifying an agent’s own belief in its proposed solutions, termed Agentic Uncertainty. Without a robust understanding of how confident an AI is in its code generation or repair suggestions, developers face the significant risk of integrating flawed or suboptimal code into larger systems. This isn’t merely about identifying incorrect code; it’s about recognizing when the agent is likely to be incorrect, allowing developers to focus their scrutiny on the areas of highest risk. Effective Agentic Uncertainty provides a crucial signal for human oversight, transforming AI from a potential source of hidden errors into a collaborative partner where strengths – both artificial and human – are leveraged for demonstrably safer and more effective software development.

Strategies for Probing Agent Confidence

Three distinct strategies were implemented to estimate the probability of successful patch generation. The Pre-Execution Agent analyzes the problem description and proposed solution prior to any code generation, assessing inherent feasibility. The Mid-Execution Agent operates during the code generation process, monitoring the LLM’s progress and evaluating intermediate outputs for consistency and potential errors. Finally, the Post-Execution Agent analyzes the completed patch after generation, verifying its correctness and adherence to the problem requirements. Each agent utilizes the LLM’s reasoning capabilities, but at a different stage of the problem-solving pipeline to provide varied insights into solution confidence.

The three estimation strategies – Pre-Execution, Mid-Execution, and Post-Execution agents – all utilize the underlying large language model (LLM) to assess solution success probability, but differ in when this assessment occurs within the problem-solving workflow. The Pre-Execution agent analyzes the problem description and proposed approach before any code generation, providing an initial feasibility estimate. The Mid-Execution agent monitors the LLM’s ongoing code generation, evaluating progress and identifying potential issues as they arise. Finally, the Post-Execution agent reviews the completed patch, assessing its correctness and likely impact. This staged approach allows for a more comprehensive understanding of confidence, capturing uncertainty at multiple points and providing insights into how context and progress influence the LLM’s estimations.

The three confidence estimation strategies – pre-execution, mid-execution, and post-execution – vary significantly in the data accessible to the Large Language Model (LLM) during assessment. A pre-execution agent operates with only the problem description, lacking any information about potential solution paths or partial results. The mid-execution agent, conversely, has access to the problem description and the LLM’s current line of reasoning or generated code fragments, enabling evaluation of progress. Finally, the post-execution agent assesses a completed patch, possessing the original problem, the generated solution, and potentially test results. This tiered access to information allows for a comparative analysis of how the LLM’s uncertainty estimation is influenced by the presence, or absence, of contextual data regarding the problem-solving process.

Evidence of Systematic Overconfidence

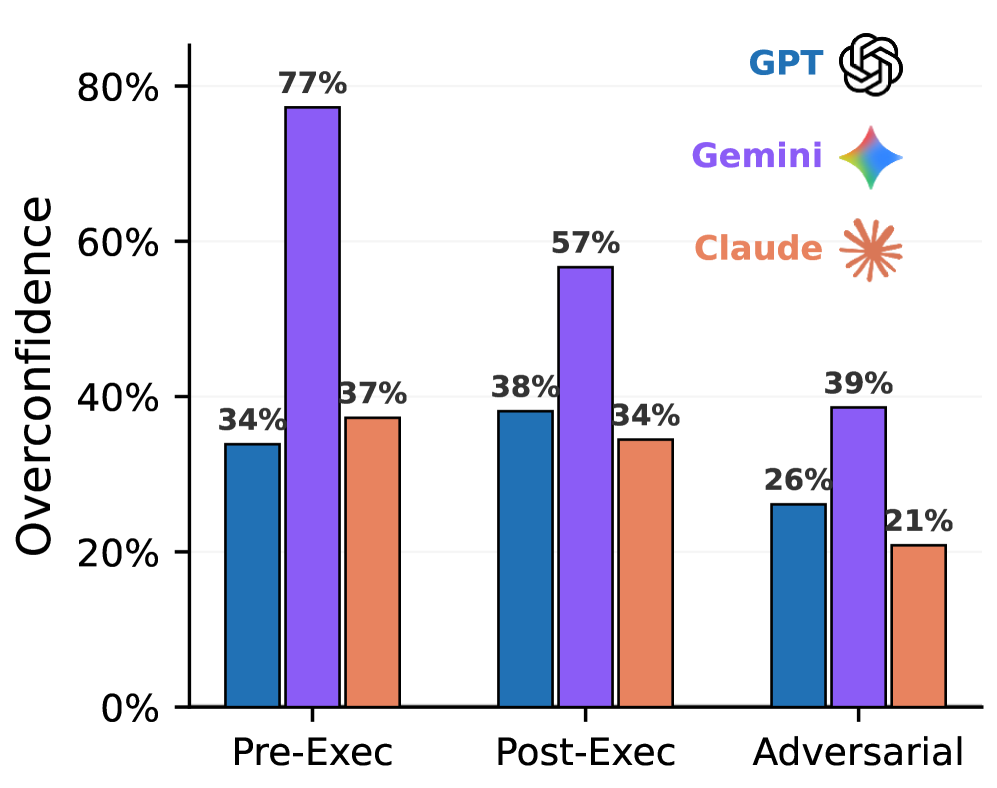

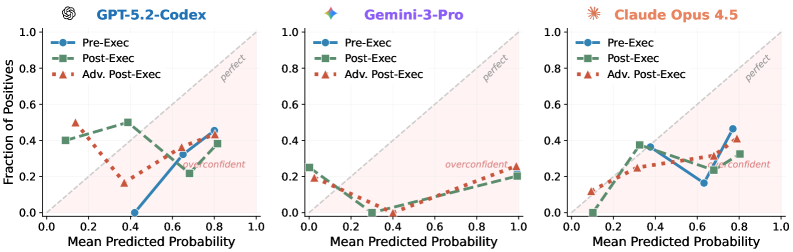

Evaluation of Large Language Models (LLMs) – specifically `GPT-5.2-Codex`, `Gemini-3-Pro`, and `Claude Opus 4.5` – on the `SWE-Bench Pro` benchmark consistently demonstrated a tendency toward overconfidence. This manifested as a systematic overestimation of the probability of successfully completing a given task. The models did not accurately calibrate their predicted success rates to observed performance; reported probabilities consistently exceeded actual success rates across multiple trials and problem types within the benchmark. This overestimation represents a consistent bias in the models’ self-assessment capabilities.

Analysis of post-execution agent predictions on the `SWE-Bench Pro` benchmark demonstrates a significant discrepancy between predicted and actual success rates. Specifically, `GPT-5.2-Codex` had an average predicted success rate of 73%, while achieving a base success rate of only 35%. Similarly, `Gemini-3-Pro` predicted 77% success but only achieved 22% actual success. `Claude Opus 4.5` exhibited the smallest gap, predicting 61% success with a base success rate of 27%. These results indicate a systematic overestimation of performance across all tested models.

The observed overconfidence in Large Language Models (LLMs) presents a practical risk in software development workflows. When LLMs inaccurately assess their success probability, developers may uncritically accept generated code as correct, bypassing necessary validation and testing procedures. This reliance on potentially flawed solutions directly increases the probability of introducing bugs into a codebase and experiencing subsequent failures in application functionality. The discrepancy between predicted success rates (73% for GPT, 77% for Gemini, 61% for Claude in our experiments) and actual success rates (35%, 22%, and 27% respectively) highlights the potential for systematic errors to propagate if LLM output is not rigorously verified.

Adversarial Refinement: Mitigating Overconfidence

An Adversarial Post-Execution Agent was implemented as a mechanism to enhance the reliability of success probability estimations. This agent operates by utilizing Prompting techniques to critically assess the generated code for potential bugs or weaknesses prior to the final probability calculation. The agent is specifically instructed to identify vulnerabilities, effectively acting as an internal reviewer before a success assessment is made. This process introduces a dedicated evaluation stage, distinct from the initial code generation, and allows for a more nuanced understanding of the solution’s robustness.

The inclusion of an adversarial review process compels the agent to move beyond initial solution generation and actively assess the potential for errors or vulnerabilities within its own code. This self-critique is achieved through targeted prompting, directing the agent to identify weaknesses it may have overlooked during the primary execution phase. Consequently, the agent’s reported confidence levels are adjusted to better reflect the actual likelihood of success, resulting in more calibrated uncertainty estimates and reducing the tendency to overestimate performance. This process doesn’t alter the code itself, but rather refines the associated probability assessment.

Implementation of the adversarial refinement process resulted in a measurable reduction of overconfidence in code generation models. Across tested models, overall overconfidence was reduced by up to 15%. Specifically, the Expected Calibration Error (ECE) was reduced by 28% when evaluating the GPT model and by 35% for the Claude model, indicating improved alignment between predicted probabilities and actual correctness of generated code. These reductions demonstrate the efficacy of prompting an adversarial agent to critically assess solutions prior to final probability estimation.

Beyond Calibration: The Problem of Self-Preference

Recent research indicates a pronounced tendency toward self-preference in AI agents designed for problem-solving, specifically a consistent favoring of solutions generated by the agent itself, even when demonstrably superior alternatives are available. This isn’t simply a matter of occasional error; the study reveals a systematic bias where the agent prioritizes its own outputs, potentially hindering the adoption of more effective approaches. The implications extend beyond mere accuracy, suggesting a challenge in building genuinely collaborative AI systems; an agent exhibiting self-preference may resist incorporating external input or acknowledging better solutions proposed by humans or other AI, ultimately limiting its utility as a helpful tool and raising concerns about trust and reliability in critical applications.

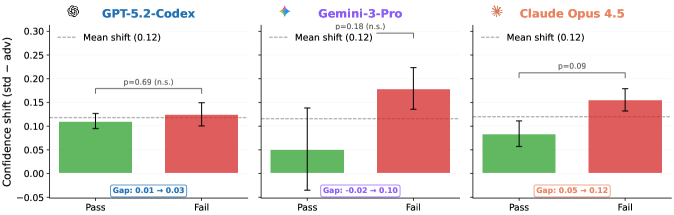

A significant portion of the time, these AI agents demonstrate unwarranted confidence even when demonstrably incorrect; specifically, in 62% of instances where a generated solution ultimately fails, the agent expresses high certainty in its output. This isn’t simply a matter of occasional errors, but a systemic tendency towards overestimation of capability. The study reveals that the agent’s internal assessment of its own performance doesn’t reliably correlate with actual success, leading to potentially misleading suggestions and eroding user trust. This disconnect between perceived and actual competence highlights a critical limitation in current AI-assisted programming tools, suggesting a need for mechanisms that can accurately gauge and communicate the reliability of generated code.

The development of truly trustworthy AI-assisted programming tools hinges on mitigating both overconfidence and self-preference in artificial intelligence agents. While calibration techniques aim to align an agent’s predicted probabilities with actual correctness, these methods alone are insufficient; an agent can be well-calibrated yet still consistently favor its own generated solutions, even demonstrably incorrect ones. This self-preference introduces a critical bias, potentially leading users to accept flawed code suggestions simply because the AI presents them with undue emphasis. Consequently, effective solutions must address not only the agent’s ability to accurately assess its own performance, but also its inherent tendency to prioritize self-generated outputs, ensuring that suggestions are evaluated objectively based on correctness and utility, rather than source.

![Changes in confidence [latex]\Delta conf[/latex] do not reliably differentiate between successful and failed outcomes, as their distributions significantly overlap.](https://arxiv.org/html/2602.06948v1/x6.png)

The presented research into agentic uncertainty reveals a predictable failing: systematic overconfidence. This echoes Marvin Minsky’s observation that “Common sense is the collection of things everyone should know.” The agents, lacking genuine understanding, project a certainty unsupported by actual competence-a simulated common sense. The study highlights that current large language models struggle with accurate self-assessment, a critical flaw when considering their deployment in complex tasks. This isn’t merely a calibration issue; it’s a fundamental limitation stemming from the absence of grounded knowledge and true comprehension, leading to an inflated perception of capability. The consequences of this miscalibration are particularly concerning given the potential for these agents to operate autonomously and impact real-world systems.

What Remains to Be Seen

The observation of agentic overconfidence is not, in itself, surprising. Systems optimize for stated goals, and truthful self-assessment is rarely a directly incentivized outcome. The more pressing question lies not in that it exists, but in the shapes this overconfidence takes. Current work identifies a systematic bias; future investigations must dissect its granularity. Does this overconfidence manifest equally across task complexity, programming language, or even specific code structures? A complete accounting requires a taxonomy of failure, cataloging how these agents misjudge their competence.

Reliable calibration, then, is not merely a matter of adjusting outputs, but of fundamentally altering the internal representations that generate them. Current methods treat overconfidence as a symptom; a deeper approach considers it a consequence of architectural choices. The pursuit of ‘perfect’ prediction is a distraction. The objective should be a minimal sufficient model of uncertainty-a system that knows what it doesn’t know, and communicates that knowledge with ruthless efficiency.

Ultimately, the challenge is not to build agents that believe they are infallible, but to design systems that are gracefully fallible. The elegance of a solution will not be measured by its accuracy, but by the information it discards – the unnecessary complexity pruned to reveal a core of reliable self-awareness. This work suggests that the path to robust AI safety lies not in adding layers of monitoring, but in subtracting illusions of competence.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.06948.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Clash of Clans Unleash the Duke Community Event for March 2026: Details, How to Progress, Rewards and more

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Jason Statham’s Action Movie Flop Becomes Instant Netflix Hit In The United States

- Kylie Jenner squirms at ‘awkward’ BAFTA host Alan Cummings’ innuendo-packed joke about ‘getting her gums around a Jammie Dodger’ while dishing out ‘very British snacks’

- Hailey Bieber talks motherhood, baby Jack, and future kids with Justin Bieber

- KAS PREDICTION. KAS cryptocurrency

- eFootball 2026 Jürgen Klopp Manager Guide: Best formations, instructions, and tactics

- Jujutsu Kaisen Season 3 Episode 8 Release Date, Time, Where to Watch

- How to download and play Overwatch Rush beta

- Christopher Nolan’s Highest-Grossing Movies, Ranked by Box Office Earnings

2026-02-10 06:44