Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new study reveals that simple AI agents can reliably optimize biomedical imaging workflows, often surpassing the performance of human experts.

This research demonstrates the power of agentic AI and automated program search in adapting pre-trained tools to new scientific imaging datasets, even with limited data.

Adapting existing computer vision tools to specialized scientific datasets presents a persistent bottleneck in modern research. In the work ‘Simple Agents Outperform Experts in Biomedical Imaging Workflow Optimization’, we address this “last mile” problem by investigating the use of AI agents to automate the code adaptation process. Our results demonstrate that a surprisingly simple agentic framework consistently generates solutions that outperform human experts in optimizing biomedical imaging pipelines. This raises the question of whether streamlined, automated approaches can fundamentally accelerate scientific discovery by reducing reliance on costly and time-consuming manual coding.

The Illusion of Clean Data: Preparing Images for Analysis

Biomedical images, whether derived from microscopy, X-ray imaging, or MRI, frequently suffer from limitations that impede accurate analysis. Inherent noise, stemming from the sensitivity of detection equipment and biological sample variability, often obscures subtle but crucial features. Simultaneously, low contrast, a common challenge in visualizing transparent or similarly toned tissues, diminishes the distinction between anatomical structures or cellular components. This combination of noise and poor contrast can mask critical details, leading to inaccurate segmentation, quantification, and ultimately, flawed biological interpretations. Consequently, addressing these limitations through careful image preparation is not merely a technical refinement, but a foundational requirement for reliable biomedical investigations.

The success of any biomedical image analysis hinges fundamentally on the quality of initial preparation. Before algorithms can detect, measure, or interpret features within an image, inherent noise and distortions must be addressed. This preprocessing stage isn’t merely a technicality; it’s a critical determinant of accuracy, as even sophisticated analytical tools will yield unreliable results if fed suboptimal data. By correcting for factors like uneven illumination, motion blur, and inherent image noise, preprocessing establishes a clean and consistent foundation upon which meaningful insights can be built. Without this foundational step, subtle but crucial biological details risk being obscured or misinterpreted, ultimately compromising the validity of the entire analysis pipeline and hindering reliable conclusions.

Biomedical images frequently require initial correction to ensure reliable analysis; techniques like Gaussian Smoothing and Affine Transformation play a crucial role in this preparatory stage. Gaussian Smoothing reduces image noise and fine detail – effectively averaging pixel values – to improve the signal-to-noise ratio, while Affine Transformation rectifies geometric distortions caused by imaging angles or sample positioning. This transformation allows for scaling, rotation, shearing, and translation, aligning images for consistent comparison and measurement. By addressing these fundamental distortions, these methods establish a standardized image format, enabling accurate segmentation, feature extraction, and ultimately, more dependable quantitative analysis in downstream tasks such as disease detection or cellular morphology studies.

Microscopy often yields images rich in subtle detail, but these are frequently masked by pervasive noise. Non-local means denoising offers a powerful solution by leveraging self-similarity within the image; instead of averaging pixels based solely on proximity, it considers all pixels exhibiting similar patterns. This approach effectively distinguishes genuine features from noise, preserving edges and fine structures that would be blurred by traditional filtering methods. The technique calculates a weighted average, giving greater prominence to pixels with high similarity, and is particularly effective in biological imaging where preserving delicate cellular structures is paramount. Consequently, non-local means denoising isn’t merely a noise reduction tool, but a critical step in enabling accurate quantitative analysis and visualization of microscopic specimens.

The Illusion of Definition: Finding Boundaries in the Noise

Image segmentation is a fundamental process in computer vision that involves dividing an image into multiple segments, or regions, to simplify and analyze the image. This partitioning is not arbitrary; segments are typically defined by shared characteristics such as color, texture, or intensity, and are intended to correspond to meaningful objects or parts of objects within the scene. The resulting segmentation allows for quantitative analysis of each region – calculating area, perimeter, or statistical measures of pixel values – and facilitates tasks like object recognition, tracking, and measurement. The precision of segmentation directly impacts the reliability of subsequent analytical processes, making it a critical step in many image-based applications, from medical imaging to autonomous vehicle navigation.

The Watershed and Contour Detection algorithms are foundational techniques in image segmentation, identifying object boundaries based on gradient magnitude and edge detection, respectively. However, both methods are highly sensitive to parameter settings. The Watershed algorithm, in particular, requires pre-processing to define markers and avoid over-segmentation due to noise, necessitating careful adjustment of marker size and distance. Contour Detection relies on parameters such as edge detection thresholds, aperture sizes for gradient calculation, and hysteresis thresholds for linking edges; improper configuration can lead to broken contours or the detection of spurious edges. Achieving optimal results with these algorithms therefore demands iterative parameter tuning, often specific to the image characteristics and the desired level of detail in the segmentation.

Adaptive Thresholding addresses the limitations of global thresholding by calculating a unique threshold value for each pixel based on a local neighborhood. This is typically achieved through algorithms like mean, Gaussian, or median filtering applied to a defined window size; the calculated value then becomes the threshold for the central pixel. By dynamically adjusting the threshold, adaptive methods are significantly more robust to variations in illumination and contrast across an image, resulting in improved segmentation accuracy compared to methods reliant on a single, globally applied threshold. Common implementations include methods described by Bradley, Roth, and Sauvola, each differing in their specific calculation and application of the local threshold.

Cellpose and MedSAM represent advancements in biomedical image segmentation through the implementation of integrated pipelines. These systems combine multiple algorithms and training data to achieve robust performance across diverse datasets and imaging modalities. Benchmarking has demonstrated consistently high F1 Scores-a metric evaluating the balance between precision and recall-when these pipelines are applied to various segmentation tasks. Specifically, MedSAM utilizes a pre-trained foundation model and promptable segmentation, while Cellpose employs a deep learning approach trained on synthetic and real cell data. The resulting high F1 Scores indicate improved accuracy and reliability in identifying and delineating biological structures compared to traditional, single-algorithm approaches.

The Mirage of Meaning: Extracting Features and Validating Assumptions

Feature extraction is the process of converting raw image data, represented as pixel values, into a numerical feature vector. This transformation relies on algorithms that identify and quantify specific characteristics within the image, such as edges, corners, textures, or color distributions. The resulting features are measurable properties that can be used for quantitative analysis, allowing for objective comparisons and pattern recognition. These features can include statistical measures like mean pixel intensity and standard deviation, or more complex descriptors derived from image processing operations like gradient magnitude and orientation. By representing images as numerical vectors, feature extraction enables the application of machine learning and statistical modeling techniques for tasks such as image classification, object detection, and image retrieval.

The Structural Similarity Index (SSIM) is a perceptual metric used to assess the similarity between two images, considering luminance, contrast, and structure. Unlike pixel-wise comparisons such as Mean Squared Error, SSIM is designed to align more closely with human visual perception. The index is calculated using a sliding window approach, comparing local patterns in the two images and generating a similarity score between -1 and 1, where 1 indicates perfect similarity. The formula incorporates three key comparison measures: luminance comparison, contrast comparison, and structure comparison, weighted to emphasize structural information. SSIM is particularly valuable in image validation tasks, such as assessing the accuracy of image reconstruction, segmentation, or compression algorithms, and is frequently used as a benchmark for evaluating image quality.

Preprocessing techniques such as Bilateral Filtering and Histogram Equalization are critical determinants of feature extraction quality. Bilateral Filtering, a non-linear edge-preserving smoothing technique, reduces image noise while maintaining important structural details, thereby improving the accuracy of subsequent feature identification. Histogram Equalization enhances image contrast by redistributing pixel intensities, making features more discernible and robust to variations in illumination. The application of these methods directly influences the statistical properties of extracted features – including texture, edges, and gradients – impacting the performance of downstream analysis and segmentation algorithms. Failure to optimize these preprocessing steps can introduce artifacts or obscure critical features, leading to inaccurate results and reduced model efficacy.

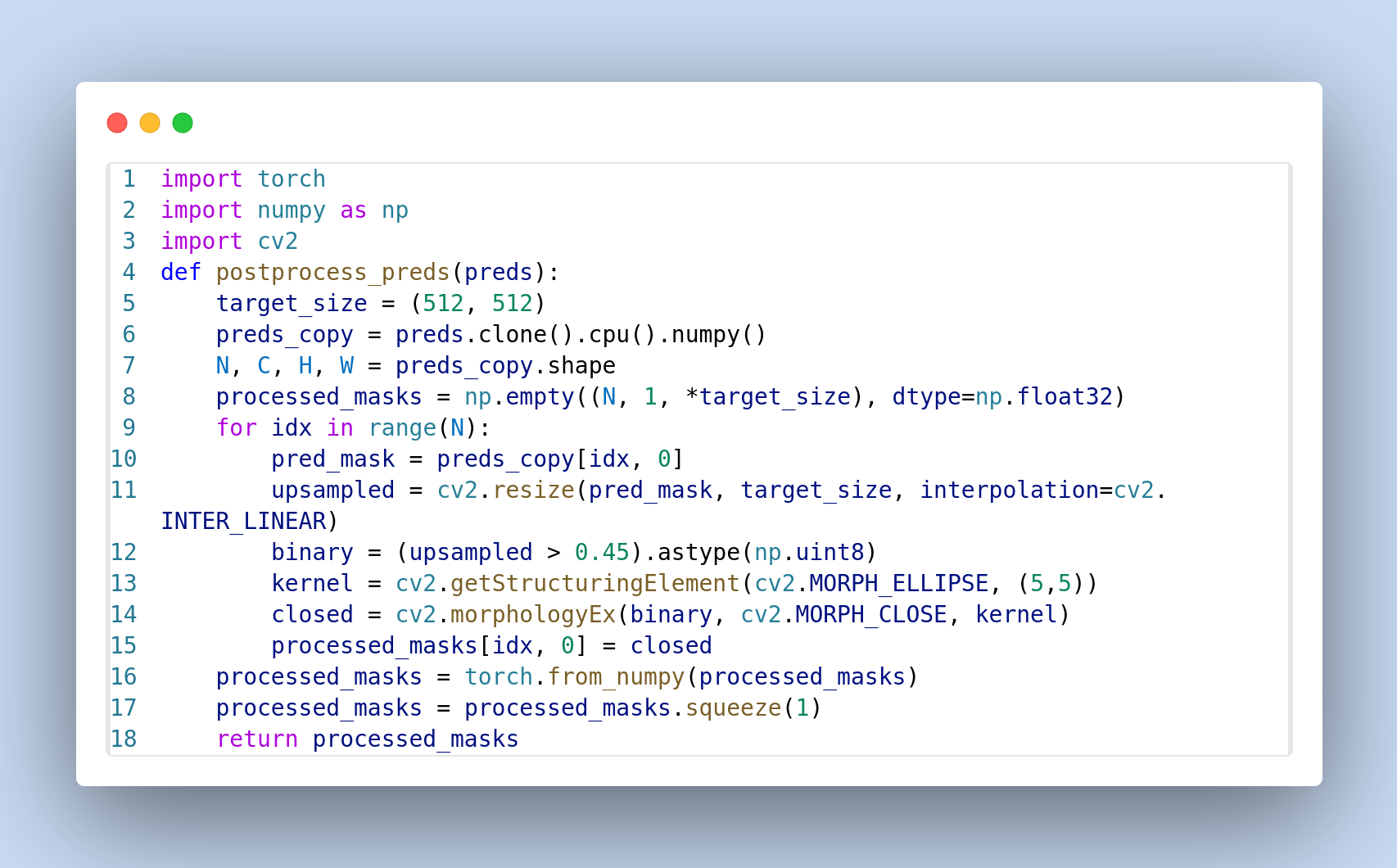

Automated image analysis pipelines, such as Polaris, integrate preprocessing steps with image segmentation to extract quantifiable data from biomedical images. Performance benchmarks demonstrate that these pipelines achieve superior F1 Scores when compared to data annotated by human experts. Specifically, the Polaris pipeline, alongside Cellpose and MedSAM, consistently outperforms expert-derived solutions in image analysis tasks. This improvement in performance is coupled with a substantial reduction in adaptation time; automated pipelines require only 1-2 days for implementation, whereas expert tuning typically demands weeks or months to achieve comparable results.

Automated feature extraction and validation pipelines demonstrate a substantial improvement in performance metrics, specifically achieving higher F1 Scores across multiple biomedical image analysis tasks compared to manual expert-derived solutions. Critically, the implementation of these pipelines drastically reduces the time required for adaptation to new datasets or image types. While traditional manual tuning by experts typically requires weeks or even months to optimize parameters and achieve acceptable results, automated pipelines can be adapted and validated within 1-2 days, significantly accelerating research and development cycles and lowering associated costs.

The pursuit of automated scientific discovery, as highlighted in this work, feels less like innovation and more like accelerating the inevitable. This paper details how a simple agentic AI can outperform experts in optimizing biomedical imaging workflows, a result that isn’t surprising. The bug tracker will inevitably fill with edge cases the agent misses, but the speed of iteration is the point. It’s a temporary reprieve from technical debt, not its elimination. Fei-Fei Li once said, “AI is not about replacing humans; it’s about augmenting our capabilities.” The paper delivers on that promise, but one suspects the augmented capability quickly becomes a dependency. The system optimizes tool adaptation, but adaptation is never truly finished. It simply shifts the burden. They don’t deploy-they let go.

What’s Next?

The demonstration that a relatively unsophisticated agentic system can rival, and occasionally surpass, human-designed workflows in scientific imaging offers a predictable outcome. The elegance of automated adaptation will inevitably encounter the messy reality of production data. Current benchmarks focus on tool selection; the true challenge lies in gracefully handling tools that fail, or worse, return subtly incorrect results. Expect the next generation of ‘revolutionary’ frameworks to devote significant effort to error propagation and uncertainty quantification – issues often dismissed during initial demonstrations.

Furthermore, the low-data regime, while a practical necessity, represents a substantial limitation. The system’s performance will undoubtedly degrade as data complexity increases. The current approach, reliant on transfer learning from pre-trained tools, merely delays the inevitable need for truly novel algorithms. The field will likely see a resurgence of interest in active learning and data augmentation techniques, repackaged as essential components of agentic AI.

Ultimately, the question isn’t whether these agents can optimize workflows, but whether the resulting optimizations are genuinely robust and maintainable. The pursuit of ‘infinite scalability’ in automated science is a familiar refrain. It’s a safe bet that, five years hence, these streamlined workflows will require significant refactoring – and a team of engineers to untangle the emergent complexity. The diagram may be elegant now, but time, and data, have a way of complicating things.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2512.06006.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Clash Royale Best Boss Bandit Champion decks

- Vampire’s Fall 2 redeem codes and how to use them (June 2025)

- Best Arena 9 Decks in Clast Royale

- Country star who vanished from the spotlight 25 years ago resurfaces with viral Jessie James Decker duet

- World Eternal Online promo codes and how to use them (September 2025)

- JJK’s Worst Character Already Created 2026’s Most Viral Anime Moment, & McDonald’s Is Cashing In

- ‘SNL’ host Finn Wolfhard has a ‘Stranger Things’ reunion and spoofs ‘Heated Rivalry’

- M7 Pass Event Guide: All you need to know

- Solo Leveling Season 3 release date and details: “It may continue or it may not. Personally, I really hope that it does.”

- Kingdoms of Desire turns the Three Kingdoms era into an idle RPG power fantasy, now globally available

2025-12-09 13:40