Author: Denis Avetisyan

Researchers have enhanced robotic tactile sensing by fusing internal vision with audio input, allowing robots to identify fabrics with human-like accuracy.

Combining internal vision and audio sensing within soft robotic fingertips enables improved fabric recognition through multimodal data fusion.

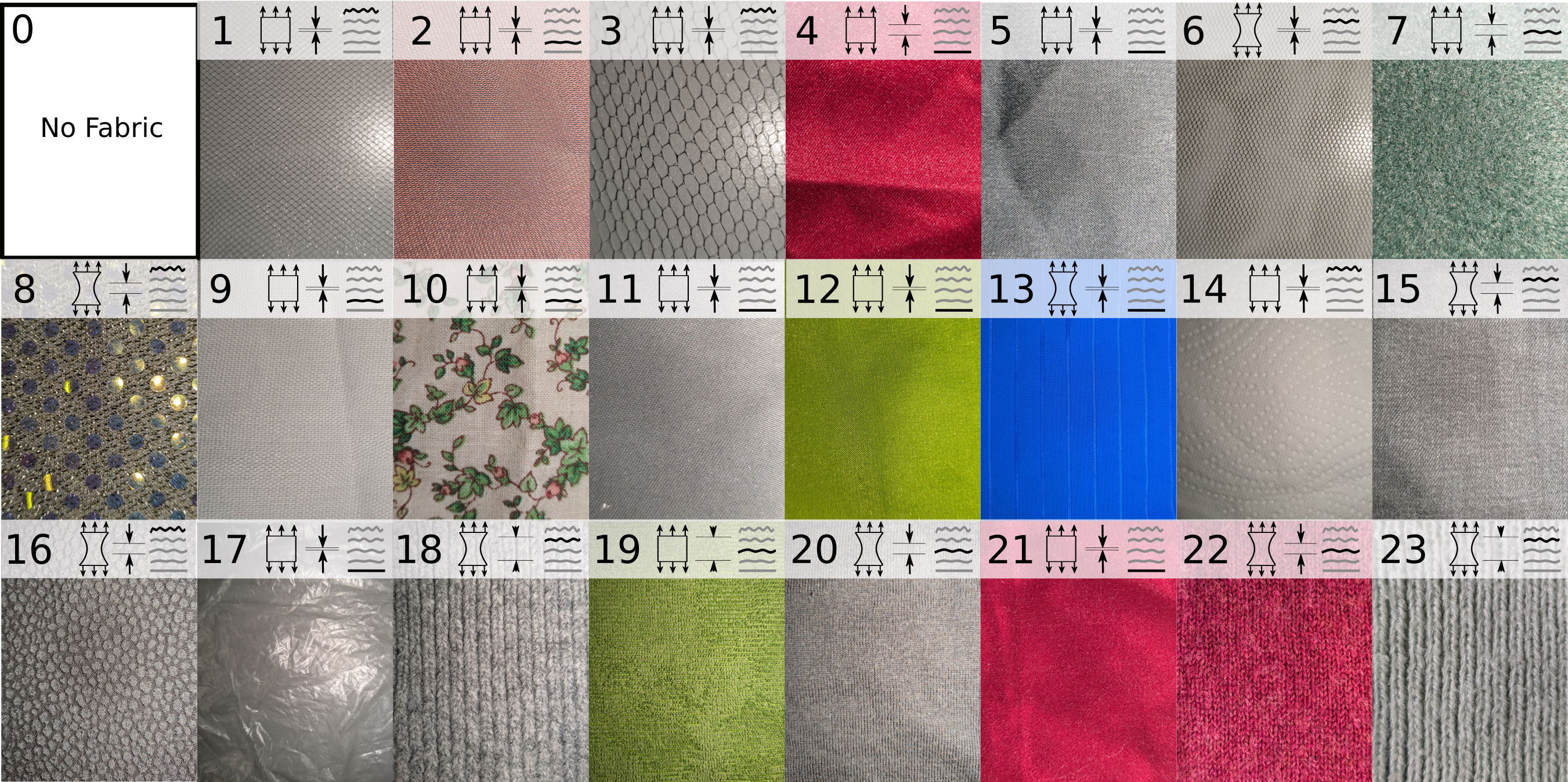

While robots struggle with the nuanced tactile perception humans effortlessly employ when identifying materials, this work-‘Adding internal audio sensing to internal vision enables human-like in-hand fabric recognition with soft robotic fingertips’-investigates a novel multimodal approach to robotic haptic perception. By integrating vision-based tactile sensing with an internal microphone capturing high-frequency vibrations, we demonstrate significant improvements in a robot’s ability to recognize fabrics, achieving up to 97% accuracy on a diverse dataset. Could this combination of internal audio and visual tactile sensing unlock more robust and adaptable robotic manipulation capabilities beyond fabric recognition?

Beyond Simple Touch: Unveiling Fabric Identity Through Sensing

The efficient and accurate identification of fabrics presents a significant challenge despite its growing importance in several key industries. Automated fabric recognition is no longer simply a convenience, but a crucial component for modern textile sorting facilities striving to handle increasing volumes of material, and for the advancement of robotic systems designed to manipulate and assemble delicate textiles. Furthermore, quality control processes within textile manufacturing benefit immensely from automated systems capable of consistently identifying defects and variations in material properties. However, the inherent complexity of fabric – stemming from variations in weave, texture, and composition – makes reliable automated identification a difficult task, demanding innovative approaches beyond traditional machine vision techniques.

Many automated fabric recognition systems predominantly utilize visual data – color, weave patterns, and texture as seen in images – yet this approach fundamentally overlooks the critical role of tactile sensation in human fabric identification. While a camera can capture surface appearance, it fails to register the subtle cues of pliability, weight, stretch, thermal conductivity, and surface friction that are instinctively processed through touch. These nuanced tactile properties are integral to defining a fabric’s identity – distinguishing silk from cotton, or linen from polyester – and are often more reliable indicators than visual characteristics alone, especially when dealing with variations in lighting, pattern complexity, or fabric deformation. Consequently, systems reliant solely on visual cues often struggle with accuracy and robustness, highlighting the necessity of incorporating tactile sensing to truly replicate human-level fabric recognition capabilities.

Mimicking the human sense of touch in robotic systems necessitates sensors that can detect a broad spectrum of textural details, extending beyond simple pressure measurements. Human fingers don’t just register if something is there, but also how it feels – a combination of coarse details, like the weave of the fabric, and subtle vibrations at high frequencies indicating smoothness or roughness. These high-frequency responses are often linked to the material’s surface texture at a microscopic level, while lower frequencies reveal the overall shape and compliance. Therefore, advanced sensors are being developed to capture this full bandwidth of tactile information, utilizing technologies like piezoelectric materials and capacitive sensing to translate minute surface interactions into quantifiable data, ultimately enabling robots to ‘feel’ fabrics in a way that approaches human dexterity.

Accurate fabric identification necessitates moving beyond merely recognizing surface-level features; a truly robust system delves into the fundamental material characteristics that define a textile’s identity. Current approaches often prioritize extracting visual or textural qualities – thread count, weave pattern, or apparent softness – but these can be misleading, especially with treated or blended materials. Instead, successful fabric recognition requires analyzing properties like stiffness, elasticity, thermal conductivity, and even subtle variations in surface friction – characteristics stemming from the fiber composition, yarn structure, and finishing processes. This holistic approach, integrating data from multiple sensor modalities and advanced analytical techniques, allows for a deeper understanding of a fabric’s inherent qualities, ultimately leading to more reliable and nuanced identification, even in complex or ambiguous cases.

A Dual-Sensor Approach: Expanding the Tactile Landscape

The developed sensor suite integrates two distinct modalities: the Minsound and the Minsight. The Minsound functions as an audio-based sensor, specifically designed to detect high-frequency tactile events through the analysis of skin vibrations. Complementing this, the Minsight utilizes a vision-based approach, employing an internal camera to measure skin deformation and capture low-frequency touch information. This combination allows for a broader range of tactile stimuli to be detected than would be possible with either sensor functioning independently, enabling a more complete representation of the tactile experience.

The Minsound sensor operates by detecting high-frequency transient vibrations in the skin, capturing dynamic tactile events. Complementing this, the Minsight sensor measures skin deformation using an internal camera system embedded within a compliant, soft shell. This camera records images of the shell’s deformation as the skin interacts with it, providing data on static or slowly varying tactile information. The combination of vibration-based detection with visual deformation analysis allows for a broader range of tactile features to be quantified than either sensor could achieve independently.

The Minsound and Minsight sensors both leverage principles of soft robotics to maximize tactile perception. This is achieved through the incorporation of compliant materials – specifically, elastomers with low durometer values – in their construction. These materials allow the sensors to conform to the shape of the contacted object and distribute forces across a wider area, increasing sensitivity to subtle changes in contact. Furthermore, compliant materials enhance adaptability by enabling the sensors to maintain contact even with irregularly shaped or moving objects, and to minimize the impact of external disturbances. This approach contrasts with traditional rigid sensors, which can lose contact or provide inaccurate readings due to limited deformation capabilities.

Combining the Minsound and Minsight sensors provides a more complete representation of tactile stimuli than either sensor operating independently. Single-modality tactile systems typically excel at detecting either high-frequency vibrations or low-frequency deformation, but struggle to accurately capture the full spectrum of touch events. The Minsound’s sensitivity to transient vibrations complements the Minsight’s measurement of sustained skin deformation, allowing the combined system to characterize both the impact and the static pressure components of a touch. This approach improves the accuracy of tactile data by resolving both temporal and spatial aspects of contact, enabling a more nuanced understanding of surface features and applied forces.

![A four-fingered robotic hand collects multimodal tactile data using a vision-based sensor [latex] ext{Minsight}[/latex] on the middle finger to measure fingertip deformation and infer contact forces, alongside a microphone-based sensor [latex] ext{Minsound}[/latex] on the thumb and palm to capture both contact and ambient audio at 48 kHz.](https://arxiv.org/html/2602.12918v1/x1.png)

Multimodal Fusion: A Symphony of Sensory Data for Robust Recognition

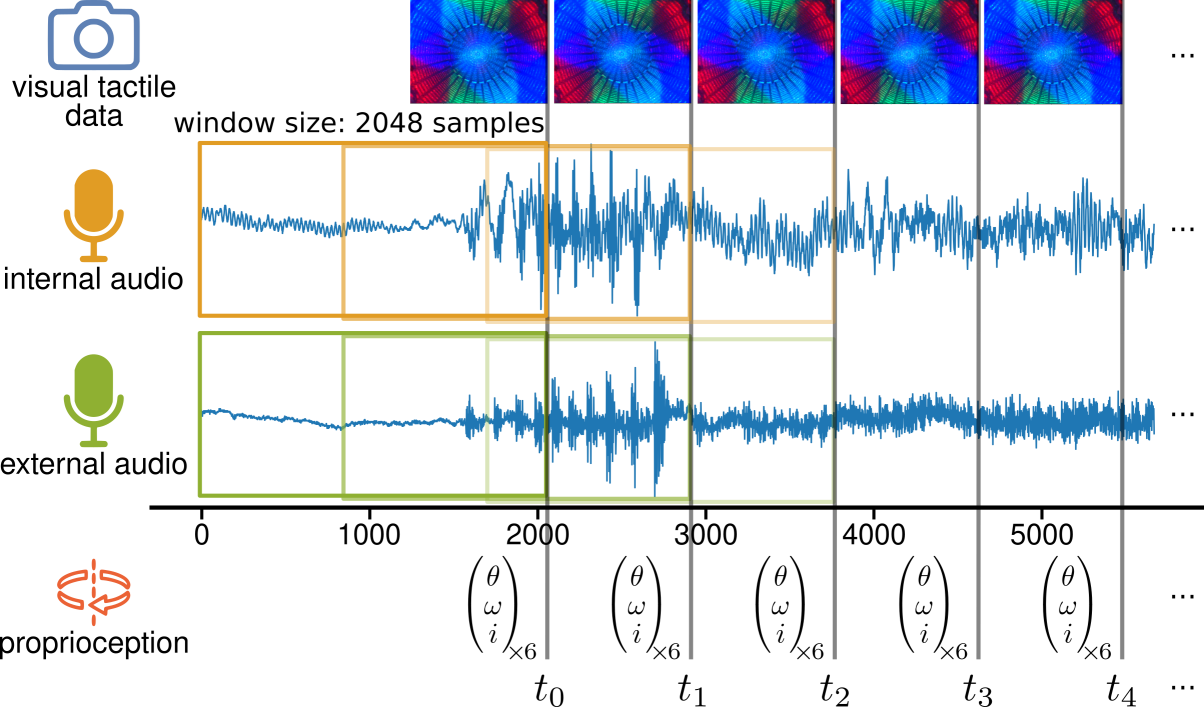

Multimodal data fusion is implemented to comprehensively characterize fabric interaction by integrating data streams from three distinct sensor modalities: audio, vision, and proprioception. Audio data is captured using both an internal microphone embedded within the sensing device and an external microphone to capture ambient sound, providing complementary acoustic information. Visual data is obtained via a dedicated camera, generating images used for optical flow analysis. Proprioceptive data, derived from the robotic hand’s joint angles and forces, provides information regarding the hand’s pose and applied forces during fabric manipulation. The combination of these modalities creates a richer, more complete representation of the interaction than any single modality could provide, enabling improved fabric identification and characterization.

The system utilizes a Transformer Architecture to process the fused multimodal data – audio, visual, and proprioceptive – allowing for the modeling of long-range dependencies and complex interactions between tactile features and fabric identity. This architecture, consisting of self-attention layers, enables the network to weigh the importance of different input features dynamically, capturing nuanced relationships that are critical for accurate fabric classification. The Transformer’s ability to process sequential data, combined with its capacity to learn contextual representations, facilitates a more robust understanding of fabric properties compared to traditional machine learning methods. Specifically, the architecture learns to correlate features extracted from optical flow, power spectral density, and robotic hand position to identify unique fabric characteristics.

The system utilizes a custom-designed robotic hand to perform dynamic in-hand exploration of fabric samples. This involves actively rubbing the fabric surface with the sensor, allowing for the collection of data that reflects varying tactile properties. This method contrasts with static measurements and enables the sensor to capture a broader range of features related to fabric texture, stiffness, and weave. The robotic hand facilitates repeatable and controlled exploration patterns, ensuring consistent data acquisition across different samples and improving the reliability of subsequent analysis performed by the Transformer model.

The system utilizes Optical Flow, computed from Minsight camera images, and Power Spectral Density (PSD) analysis of Minsound audio as primary input features for the Transformer model. Initial classification testing, employing only the internal microphone of the Minsound device, yielded an accuracy of 95.06%. Performance was further enhanced to 97.75% by integrating data from an external microphone and proprioceptive sensors from the robotic hand, demonstrating the benefit of multimodal data fusion for improved fabric recognition capabilities. These features provide quantifiable data regarding texture and interaction dynamics, allowing the model to effectively discriminate between fabric types.

Towards Intelligent Textiles: A Future Woven with Adaptive Robotics

Recent advancements have shown it is now feasible to imbue robotic systems with a sense of touch comparable to that of humans. This achievement stems from the development of sophisticated sensor arrays and algorithms capable of discerning subtle variations in texture, pressure, and deformation. Unlike traditional robotic sensors that provide limited tactile information, these new systems can detect nuances previously imperceptible to machines, allowing for delicate manipulation of objects and improved interaction with complex environments. The ability to replicate human tactile sensitivity opens doors to applications demanding fine motor skills and precise feedback, effectively bridging the gap between automated processes and the dexterity of human touch.

The development of sensitive tactile sensors promises a revolution in how textiles are handled by automated systems. Currently, tasks like sorting fabrics by weight, weave, or defect rely heavily on human inspection, a process that is both costly and prone to inconsistency. This new technology enables robotic systems to ‘feel’ fabrics with a level of nuance approaching human sensitivity, allowing for accurate identification of material properties and the detection of even subtle flaws. Consequently, automated quality control becomes significantly more efficient and reliable, reducing waste and improving product consistency. Furthermore, the ability to delicately manipulate fabrics opens doors for fully automated garment assembly and other complex textile manufacturing processes, potentially reshaping the industry through increased productivity and reduced labor costs.

The principles underpinning this tactile sensing technology extend far beyond automated textile handling, offering substantial advancements for fields demanding nuanced touch feedback. Specifically, the development of a robust and sensitive artificial touch system holds immense promise for the next generation of prosthetic limbs, enabling more natural and intuitive control for users. Similarly, surgical robotics could benefit significantly from this technology, allowing surgeons to perform delicate procedures with greater precision and feel, potentially minimizing invasiveness and improving patient outcomes. By replicating the complexities of human tactile perception, this multimodal approach facilitates the creation of robotic systems capable of interacting with the world in a more sophisticated and adaptable manner, opening doors to enhanced functionality and performance in a variety of critical applications.

The system’s robust performance in challenging, real-world conditions represents a significant advancement in tactile sensing. Evaluations conducted in noisy environments demonstrate an impressive 91.57% classification accuracy when utilizing the complete sensor suite, a figure dramatically higher than the 41.15% achieved by the Minsight sensor alone. This substantial improvement highlights the efficacy of the multimodal approach in filtering interference and extracting meaningful data from complex tactile inputs. By effectively emulating the nuanced sensitivity of human touch, this technology paves the way for more reliable and adaptable robotic systems, fostering new opportunities for seamless human-robot collaboration and the automation of tasks demanding delicate manipulation and precise feedback.

![A multimodal classification architecture processes [latex]N=200[/latex] time steps of fabric interaction data by encoding each modality, concatenating and normalizing the features, adding positional embeddings, and then utilizing either a three-layer multi-head attention network or a temporal convolutional network to classify the interactions via a two-layer fully connected network with a softmax output.](https://arxiv.org/html/2602.12918v1/x3.png)

The pursuit of nuanced tactile perception, as demonstrated in this work, necessitates a holistic approach. The integration of auditory input with visual and tactile data isn’t merely additive; it fundamentally alters the system’s understanding of material properties. If the system looks clever, it’s probably fragile – a lone vision system, attempting to deduce fabric identity, embodies this fragility. Vinton Cerf observed, “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” This research doesn’t strive for magic, but for a demonstrable understanding-a system where internal audio sensing, complementing vision, allows the robotic fingertip to ‘feel’ fabric characteristics with a fidelity approaching human capability. Structure dictates behavior, and here, the architecture prioritizes multimodal fusion to yield robust fabric recognition.

Beyond the Surface

The convergence of visual and auditory tactile sensing, as demonstrated, is not merely an incremental improvement, but a subtle shift in how robotic perception is conceived. The current work rightly focuses on fabric recognition, yet it hints at a larger truth: a sensor is not an isolated receptor, but a node within a complex network. One cannot simply add an internal microphone and expect comprehensive understanding; the ‘ear’ must be integrated with the ‘eye’, and both must function within a system that accounts for material properties, dynamic interactions, and the inherent ambiguity of the physical world.

Future iterations will inevitably explore more sophisticated fusion algorithms. However, the real challenge lies in moving beyond feature-level integration towards a more holistic, ‘embodied’ perception. The question isn’t simply ‘what does this fabric look and sound like?’, but ‘what does it feel like to manipulate it?’. This necessitates a deeper understanding of the interplay between deformation, force, and the resulting acoustic and visual signatures – a system where the structure of the sensor dictates its behavioral response.

Ultimately, the pursuit of human-like tactile perception is not about replicating biological complexity, but about distilling its elegance. A successful system will not be burdened by superfluous detail, but defined by a clarity of design – a simplicity that belies the sophistication of its underlying mechanisms. The path forward demands not more sensors, but a more refined architecture.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.12918.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Star Wars Fans Should Have “Total Faith” In Tradition-Breaking 2027 Movie, Says Star

- Jessie Buckley unveils new blonde bombshell look for latest shoot with W Magazine as she reveals Hamnet role has made her ‘braver’

- Call the Midwife season 16 is confirmed – but what happens next, after that end-of-an-era finale?

- eFootball 2026 is bringing the v5.3.1 update: What to expect and what’s coming

- Robots That React: Teaching Machines to Hear and Act

- Denis Villeneuve’s Dune Trilogy Is Skipping Children of Dune

- Country star Thomas Rhett welcomes FIFTH child with wife Lauren and reveals newborn’s VERY unique name

- Taimanin Squad coupon codes and how to use them (March 2026)

- Decoding Life’s Patterns: How AI Learns Protein Sequences

- Mobile Legends: Bang Bang 2026 Legend Skins: Complete list and how to get them

2026-02-16 15:49