Author: Denis Avetisyan

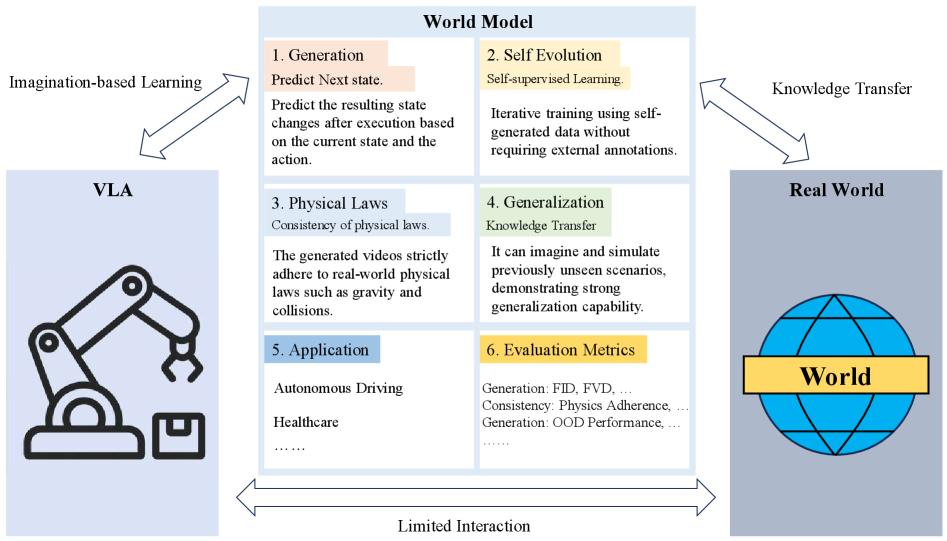

The next generation of AI demands more than just realistic simulations-it requires world models grounded in physical laws to enable reliable and safe decision-making.

This review argues for a shift from visually compelling world models to actionable simulators emphasizing physical grounding, causal reasoning, and generalization for robust AI performance.

While current AI systems excel at generating plausible scenarios, a fundamental disconnect remains between visual fidelity and genuine world understanding. This survey, ‘From Generative Engines to Actionable Simulators: The Imperative of Physical Grounding in World Models’, argues that effective world models require a shift from simply predicting pixels to encoding causal structure and respecting physical constraints. We demonstrate that a model’s true value lies not in realistic rollouts, but in its ability to support counterfactual reasoning and robust long-horizon planning, particularly in safety-critical applications where trial-and-error is impossible. Can we redefine world models as actionable simulators, capable of reliable decision-making grounded in physical truth, rather than sophisticated visual engines?

The Illusion of Understanding: Why Pattern Recognition Isn’t Intelligence

While contemporary artificial intelligence systems demonstrate remarkable proficiency in identifying patterns within datasets, this ability often plateaus when confronted with novel situations requiring genuine comprehension. These systems frequently excel at statistical correlation – recognizing that certain inputs consistently precede specific outputs – but lack the capacity to extrapolate this knowledge to contexts beyond their training. This limitation stems from a reliance on surface-level associations rather than a deeper understanding of underlying principles, resulting in brittle performance and an inability to generalize effectively. Consequently, an AI might accurately categorize images of cats but fail to recognize a cat in an unusual pose or lighting condition, highlighting the crucial distinction between pattern recognition and true, robust intelligence.

Contemporary artificial intelligence systems, while adept at identifying correlations within datasets, frequently demonstrate a surprising lack of foresight when confronted with novel situations. This limitation stems from an inability to accurately simulate the repercussions of actions or predict future states of the environment. Consequently, even highly-trained algorithms can falter when faced with scenarios slightly deviating from their training data – a phenomenon known as brittle performance. Unlike humans, who intuitively understand physical principles like gravity and momentum, these systems often treat the world as a static collection of inputs, failing to grasp the dynamic interplay of cause and effect. This deficiency hinders their ability to generalize knowledge and adapt to the complexities of the real world, highlighting the need for AI that doesn’t just recognize patterns, but actively models and anticipates the consequences of events.

The pursuit of truly intelligent systems necessitates a departure from algorithms focused solely on recognizing patterns and a move towards constructing comprehensive internal world models. These models aren’t merely about forecasting future events; they represent a system’s attempt to encapsulate an understanding of underlying causal relationships and physical laws. By building an internal representation of how the world operates, an artificial intelligence can move beyond brittle, data-dependent performance and exhibit robust adaptability in novel situations. This approach allows for reasoning about potential consequences, planning effective actions, and ultimately, achieving a form of intelligence that isn’t limited by the specific data it was trained on-instead, it can generalize and learn from experience in a manner akin to biological intelligence. The capacity to simulate and understand the ‘how’ and ‘why’ behind phenomena, rather than simply ‘what’ happens, is therefore pivotal for developing adaptable and resilient AI.

Truly intelligent systems require more than the ability to anticipate what will happen next; they necessitate a deep, internalized grasp of how things happen. Current artificial intelligence frequently excels at statistical prediction, identifying correlations without comprehending the underlying causal mechanisms. However, robust intelligence demands the construction of internal models that simulate the fundamental principles governing the physical world – gravity, inertia, object permanence, and more. These aren’t simply tools for forecasting; they are representations of how the world works, allowing a system to not only predict an outcome but also to understand why it occurs, reason about interventions, and generalize knowledge to novel situations. Such embodied simulation provides the foundation for adaptable behavior, enabling systems to navigate uncertainty and respond effectively to unforeseen circumstances, moving beyond brittle performance reliant on pre-programmed responses.

Mapping the Mess: Structuring Reality for Artificial Minds

Raw pixel data, while providing a complete visual record of an environment, is inefficient for representing state information in a world model due to its high dimensionality and lack of explicit relationships between elements. Effective world models necessitate structuring this data into more compact and interpretable formats; this involves identifying and representing objects, their properties, and the relationships between them. This structured representation reduces computational demands for processing and reasoning, enabling efficient storage, retrieval, and manipulation of environmental knowledge. Transitioning from pixel-level data to symbolic or geometric representations – such as object bounding boxes, semantic segmentation, or 3D meshes – allows for higher-level reasoning about the world and facilitates predictive capabilities beyond simple pattern recognition.

4D Dynamic Meshes represent environments as volumetric data that evolves over time, explicitly encoding object shapes, positions, and deformations across multiple timesteps. This contrasts with implicit representations like neural radiance fields, offering direct access to geometric properties for physics simulation and path planning. Causal Interaction Graphs, conversely, focus on relationships between objects, defining how actions propagate through the environment. Nodes represent entities, and edges denote causal links – for example, a pushing action causing a block to move. These graphs facilitate reasoning about consequences and predicting future states based on interventions. Both methods prioritize interpretability; the mesh data is directly visualizable, and the graph structure allows for tracing causal pathways, aiding debugging and verification of the world model’s internal logic.

Initial state reconstruction in world modeling systems frequently utilizes 2D pixel-level extrapolation techniques to establish a preliminary environmental representation. These methods analyze visual data from sensors – typically cameras – to infer spatial relationships and object boundaries beyond the immediate field of view. By extending observed pixel patterns, systems can generate a more complete, albeit initially coarse, depiction of the surroundings. This extrapolated 2D data then serves as input for more complex, structured interfaces like 4D Dynamic Meshes or Causal Interaction Graphs, providing a foundational layer of spatial information upon which these systems can build detailed and interpretable world models. The accuracy of this initial extrapolation directly impacts the efficiency and reliability of subsequent reasoning and planning processes.

Structured world model interfaces directly support advanced cognitive functions by enabling predictive processing. The explicit representation of environmental state and dynamics allows an agent to perform hypothetical reasoning – evaluating potential actions and their likely consequences within the modeled environment. This capability is foundational for planning, as it facilitates the selection of action sequences designed to achieve specific goals, assessed through simulation of the world model. Furthermore, repeated simulations, informed by the structured data, allow for the generation of probabilistic future states, enabling the agent to anticipate events and adapt its behavior accordingly. The fidelity of these simulations is directly correlated to the completeness and accuracy of the underlying world model representation.

The Illusion of Learning: Self-Improvement Through Simulated Experience

Self-Evolution represents an iterative process for improving internal world models. This framework functions by repeatedly generating potential future states, imagining the consequences of actions within those states, and incorporating feedback – typically in the form of prediction error or reward signals – to refine the model’s accuracy. This cycle of generation, imagination, and feedback allows the system to learn from simulated experience, improving its ability to predict and navigate complex environments. The process is not simply about memorization; instead, it focuses on building a robust and adaptable model capable of generalization beyond the specific scenarios encountered during training.

Physics-informed constraints are integrated into simulations by leveraging pre-existing models of intuitive physics – the inherent human understanding of how physical objects behave. These constraints define acceptable parameters for simulated events, such as gravity, friction, and collision dynamics, ensuring outputs align with real-world physical laws. Implementation typically involves loss functions that penalize deviations from these established physical principles during the simulation process. This approach minimizes unrealistic or impossible scenarios, enhancing the validity and transferability of the simulated data for applications like robotics, computer graphics, and predictive modeling. The use of these constraints is crucial for creating simulations that are not only visually plausible but also fundamentally consistent with observed physical phenomena.

Uncertainty-Aware Imagination incorporates probabilistic modeling into the simulation process, allowing the system to not only generate plausible future states but also to quantify the confidence level associated with each prediction. This is achieved through techniques like Bayesian Neural Networks or ensemble methods, which output a distribution over possible outcomes rather than a single deterministic value. The generated distributions reflect the inherent uncertainty in predicting complex systems, particularly when extrapolating beyond observed data. By explicitly representing this uncertainty, the system can prioritize exploration of scenarios where predictions are less certain, improving the robustness and reliability of learned world models and facilitating more effective planning and decision-making under ambiguous conditions.

Generative rollouts facilitate learning by creating a variety of simulated experiences, effectively increasing the dataset available for model training. This process involves repeatedly generating new states within the simulation and using them to refine the agent’s understanding of the environment. The performance of these generated states is commonly assessed using the Fréchet Inception Distance (FID) and Fréchet Video Distance (FVD) metrics. These metrics quantify the similarity between the distributions of generated and real-world observations; lower FID/FVD scores indicate a higher degree of realism and a better alignment between the simulation and observed data. Utilizing these metrics allows for quantitative evaluation and iterative improvement of the generative process within the simulated environment.

The Inevitable Disconnect: From Simulation to Real-World Impact

The development of Actionable Simulators represents a pivotal shift in artificial intelligence, moving beyond predictive modeling to systems capable of actively influencing real-world outcomes. These aren’t merely digital recreations of environments; they are sophisticated world models designed to anticipate the consequences of actions and, crucially, to guide planning and control. By accurately forecasting how different interventions will unfold, these simulators empower AI agents – and potentially human operators – to make informed decisions in complex scenarios. Imagine a robotic system navigating a disaster zone, not by trial and error, but by pre-planning a route through the simulator, optimizing for speed, safety, and resource utilization. Or consider a city planner using a digital twin to assess the impact of new infrastructure projects before a single brick is laid. The success of these systems hinges on their ability to not only mirror reality but to serve as a reliable blueprint for future action, effectively bridging the gap between digital foresight and physical execution.

Medical world models, powered by counterfactual reasoning, represent a paradigm shift in healthcare innovation. These sophisticated systems move beyond simple prediction to explore “what if” scenarios, enabling a deeper understanding of patient health and potential interventions. By simulating the effects of different treatments or diagnostic pathways, these models can personalize care plans with unprecedented accuracy. Researchers are utilizing counterfactual analysis to identify optimal drug candidates, predict patient responses to therapies, and even diagnose diseases earlier by assessing how subtle changes in patient data would alter outcomes. This capability promises not only to improve treatment efficacy but also to accelerate drug discovery by virtually testing countless combinations before clinical trials, ultimately reducing costs and bringing life-saving therapies to patients faster.

The promise of artificial intelligence increasingly hinges on the ability to bridge the gap between digital training grounds and the complexities of the physical world-a process known as Sim-to-Real Transfer. This technique allows systems to learn policies and strategies within a simulated environment, then deploy that knowledge to control actual robotic systems or navigate real-world scenarios without extensive retraining. Critical to successful implementation is the measurement of Sim-to-Real Correlation, a metric that quantifies the fidelity between the simulation and reality. A high correlation indicates the simulation accurately reflects the physical world, ensuring the learned behaviors transfer reliably and effectively. Without robust Sim-to-Real Correlation, deployed systems may encounter unexpected failures or exhibit diminished performance due to discrepancies between the training environment and the actual conditions they face, thus hindering the widespread adoption of AI in practical applications.

The creation of consistently reliable artificial intelligence necessitates a focus on invariant constraints – fundamental principles that remain true regardless of environmental changes or unforeseen circumstances. Systems designed with these constraints at their core demonstrate enhanced robustness when navigating complex, real-world environments. Maintaining these invariants isn’t simply about preventing errors; it’s about ensuring predictable and safe behavior even when faced with novelty. Consequently, evaluation of such systems frequently centers on quantifiable metrics like Task Success Rate – the percentage of times a system achieves a defined objective – and Policy Return, which measures the cumulative reward gained through a system’s decision-making process. These metrics provide concrete data regarding a system’s utility and its ability to consistently perform as expected, establishing a foundation for trustworthy AI deployment.

The pursuit of ever-more-complex ‘world models’ feels like building sandcastles before the tide rolls in. This paper correctly points out the shift needed – from pretty pictures to predictable simulations. It’s not about fooling the eye, but about building systems that understand cause and effect, even if the resulting ‘simulation’ looks like a wireframe diagram. As Linus Torvalds once said, ‘Most programmers think that if their code works, it’s finished. But I think it’s just the beginning.’ The same applies here; achieving visually plausible generation is merely the first step. true progress lies in creating actionable simulators, even if they lack photorealism, because ultimately, a system’s utility isn’t judged by its aesthetics, but its reliability – and consistent crashes, at least, are predictable.

What’s Next?

The pursuit of ‘actionable simulators’ feels less like a breakthrough and more like acknowledging the inevitable. Every generative engine, no matter how convincing its visual fidelity, will eventually betray a lack of fundamental understanding when pressed to interact with a non-idealized world. The field will likely see a surge in attempts to retrofit causal reasoning onto existing architectures, a process akin to bolting logic onto intuition – often messy, frequently brittle. The true test won’t be generating plausible futures, but reliably predicting the consequences of intervention, and that demands a level of physical grounding current frameworks conspicuously lack.

A critical bottleneck will be data. Physics-informed machine learning offers a potential escape from the data hunger of purely empirical methods, but even these approaches require sufficient examples to constrain the solution space. Expect a proliferation of synthetic data generation techniques, each introducing its own biases and simplifications. The question, then, becomes not just how to create these simulators, but how to rigorously validate them in regimes beyond their training distribution – a problem notoriously resistant to elegant solutions.

Ultimately, this shift from generation to simulation is merely a recalibration. It’s a tacit admission that abstraction, while convenient, is always lossy. Every abstraction dies in production. The goal isn’t to build perfect models of the world, but rather to create systems that fail predictably, and can be safely contained when – not if – they do. The elegance of the theory will be measured not by its initial promise, but by the grace with which it degrades.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.15533.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- VCT Pacific 2026 talks finals venues, roadshows, and local talent

- Will Victoria Beckham get the last laugh after all? Posh Spice’s solo track shoots up the charts as social media campaign to get her to number one in ‘plot twist of the year’ gains momentum amid Brooklyn fallout

- EUR ILS PREDICTION

- Vanessa Williams hid her sexual abuse ordeal for decades because she knew her dad ‘could not have handled it’ and only revealed she’d been molested at 10 years old after he’d died

- Dec Donnelly admits he only lasted a week of dry January as his ‘feral’ children drove him to a glass of wine – as Ant McPartlin shares how his New Year’s resolution is inspired by young son Wilder

- SEGA Football Club Champions 2026 is now live, bringing management action to Android and iOS

- The five movies competing for an Oscar that has never been won before

- Binance’s Bold Gambit: SENT Soars as Crypto Meets AI Farce

- Invincible Season 4’s 1st Look Reveals Villains With Thragg & 2 More

- CS2 Premier Season 4 is here! Anubis and SMG changes, new skins

2026-01-24 00:32