Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research reveals a significant gap between the types of claims users seek to verify and the focus of current fact-checking efforts.

A demand-side analysis of fact-checking requests shows users prioritize simple, verifiable claims, while existing benchmarks emphasize complex and often sensationalized content.

Despite growing concern over the spread of misinformation, research has largely focused on the supply of false claims, neglecting what drives public demand for verification. The study ‘What do people want to fact-check?’ addresses this gap by analyzing [latex]\mathcal{N}=2500[/latex] user-submitted claims to an AI fact-checking system, revealing a preference for simple, empirically verifiable statements about present-day observables. This contrasts sharply with existing fact-checking benchmarks and raises the question of whether current AI systems are aligned with the actual informational needs of the public. How can we better bridge the gap between what people want to fact-check and the capabilities of automated verification tools?

The Evolving Demand for Veracity

The digital age has unleashed an unprecedented surge in user-generated claims circulating online, dramatically outpacing the capacity of traditional fact-checking methods. Previously, journalistic organizations largely dictated what constituted ‘news’ worthy of verification; now, a vast and diverse array of assertions-ranging from local rumors to niche scientific questions-emerge directly from the public. This shift necessitates a fundamental rethinking of fact-checking priorities, moving beyond established news cycles and focusing instead on the real-time informational needs expressed by internet users. The sheer volume and breadth of these claims present significant challenges, demanding scalable and adaptable systems capable of handling a far wider spectrum of topics and levels of evidence than previously considered. Effectively addressing this new landscape requires a proactive approach centered on identifying and verifying the claims that matter most to the public, rather than simply reacting to established media narratives.

The contemporary information landscape is characterized by a relentless surge in user-generated claims, extending far beyond the scope of traditional journalistic scrutiny. These assertions aren’t limited to established news topics; they encompass an extraordinarily diverse range of subjects, from niche hobbies and local events to personal opinions and rapidly evolving conspiracy theories. Crucially, the verifiability of these claims varies dramatically – some are easily confirmed or debunked with readily available evidence, while others are ambiguous, require specialized knowledge, or lack sufficient supporting information. Consequently, effective fact-checking systems must move beyond narrow domains and embrace the ability to assess claims across a full spectrum of complexity and evidentiary support, accommodating both straightforward assertions and those demanding nuanced investigation.

The evolving landscape of online information requires a fundamental shift in how veracity is assessed, moving beyond simply checking claims prioritized by journalists or researchers. A focus on ‘demand-side evidence’ – essentially, understanding what questions people are actively trying to answer – is now crucial. Recent research highlights a significant disconnect between existing fact-checking benchmarks and actual user behavior; datasets like FEVER tend to concentrate on claims originating from established news sources and specific domains, whereas user queries demonstrate a far broader and more diverse distribution of topics and assertion types. This mismatch suggests that current automated systems, trained on these limited datasets, may struggle to effectively address the real-world verification needs of online users, necessitating new approaches that prioritize responsiveness to genuine public demand for information.

Deconstructing Claims: A Taxonomy of Truth

User-generated claims exhibit substantial diversity in their core assertions. Descriptive claims present statements about observable states of the world, focusing on what is, such as “The population of Tokyo is 14 million.” Causal claims, conversely, propose relationships between events or entities, arguing that one factor influences another – for example, “Increased exercise improves cardiovascular health.” Finally, normative claims express subjective evaluations or value judgments, indicating what ought to be, like “Universal healthcare is a moral imperative.” Accurate claim analysis necessitates distinguishing between these types, as each demands a different verification strategy and evidentiary standard.

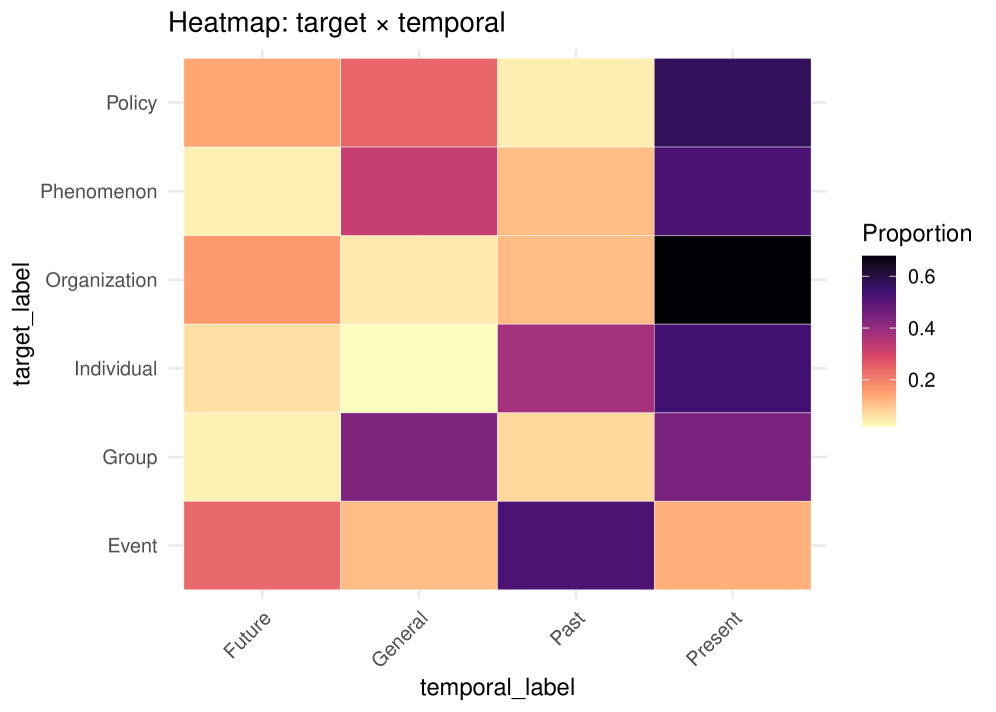

Claim categorization by target is a fundamental step in verification processes. Claims are differentiated based on what or whom they address: ‘individual’ targets refer to specific people; ‘phenomenon’ targets concern broader concepts, events, or states of affairs; and ‘other entities’ encompass organizations, locations, or objects. Accurate target identification is critical because it dictates the scope of evidence retrieval; verifying a claim about an individual necessitates biographical or personal records, while a claim concerning a phenomenon requires data related to that specific concept. Internal research indicates that 51% of user-generated claims target broad phenomena, a divergence from the 54% focus on individuals observed in the FEVER dataset, highlighting the importance of systems capable of handling both claim types effectively.

Determining the temporal orientation of a claim – whether it concerns current conditions or past events – is a critical step in evidence retrieval, as it dictates the timeframe for searching relevant data. Analysis of user-generated claims reveals that 51% target broad phenomena, differing significantly from the 54% focus on individual entities observed in the FEVER dataset. This discrepancy highlights the need for tailored evidence retrieval strategies that account for both the subject of the claim and its temporal scope; systems designed for datasets emphasizing individual claims may perform suboptimally when applied to queries concerning broader phenomena.

An Infrastructure for Discernment: AI and the Verification Process

An AI Verification System is necessary to address the increasing volume of fact-checking demands exceeding manual capacity. These systems employ techniques such as domain classification – identifying the subject area of a claim (e.g., politics, science, entertainment) – to route verification requests to appropriate resources and expertise. Temporal orientation analysis further streamlines the process by assessing the claim’s timeframe and identifying relevant evidence based on when the claim was made and when information became available. By automating initial categorization and evidence retrieval, these AI systems significantly reduce the workload for human fact-checkers, enabling broader coverage and faster response times.

Performance evaluation of AI verification systems frequently utilizes benchmark datasets such as FEVER; however, significant domain distribution discrepancies can impact the reliability of these evaluations. Analysis of user queries revealed that only 16% pertain to the ‘Entertainment’ domain, a considerable difference from the 63% representation in the FEVER benchmark. Conversely, user queries demonstrate a higher prevalence of ‘Science/Tech’ (22%) and ‘Health/Med’ (14%) topics, compared to the 3% and 2% found in FEVER, respectively. These distributional shifts suggest that benchmark performance may not accurately reflect real-world system efficacy and necessitate careful consideration when interpreting evaluation results.

Epistemic outsourcing, in the context of AI-powered verification systems, describes the delegation of knowledge-based tasks – specifically, the assessment of truth and accuracy – to automated processes and external data sources. Rather than relying solely on human fact-checkers, these systems utilize algorithms and databases to evaluate claims. This delegation extends to multiple stages, including claim retrieval, evidence gathering, and evidence evaluation, with AI determining the veracity of information based on predefined criteria and data access. The reliance on automated systems necessitates careful consideration of data provenance, algorithmic bias, and the potential for inaccuracies inherent in both the data and the processes used for verification.

The Limits of Certainty: Navigating the Spectrum of Verifiability

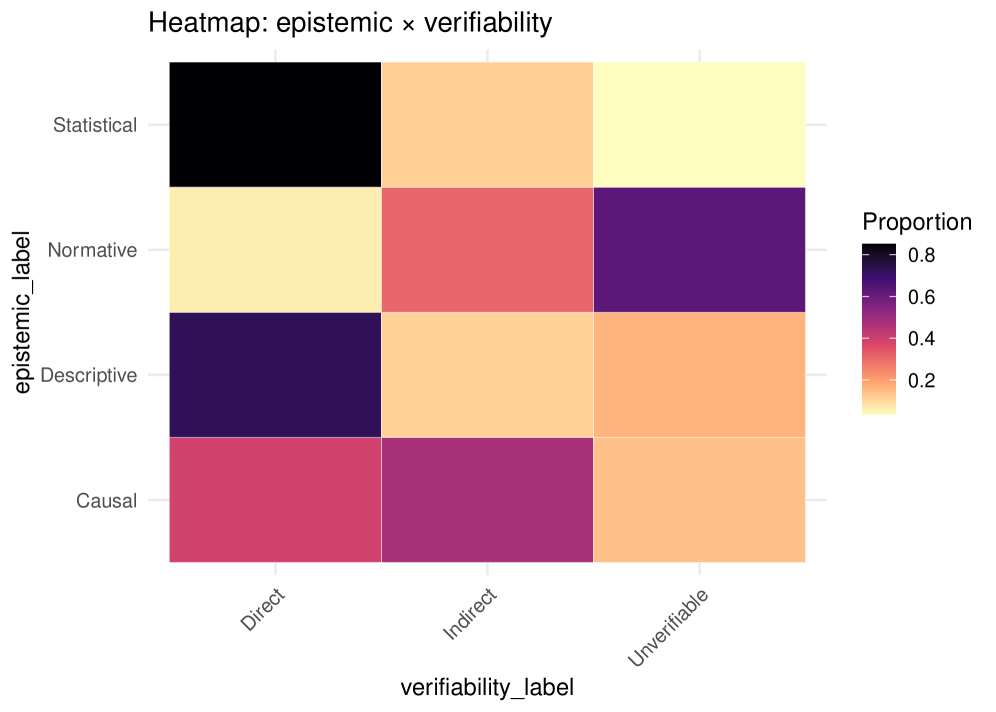

The spectrum of claim verifiability is surprisingly broad, extending far beyond simple true or false assessments. Some assertions lend themselves to direct verifiability – facts readily confirmed through authoritative public records like census data or legislative statutes. However, a significant number of claims necessitate indirect verifiability, demanding specialized knowledge and analytical techniques for evaluation. These might involve complex scientific models to project climate change impacts, expert interpretation of economic indicators to assess market stability, or statistical analysis of epidemiological data to determine disease prevalence. This reliance on inference, rather than straightforward lookup, introduces inherent uncertainty and necessitates careful consideration of the methodologies employed, acknowledging that conclusions, while informed, are not absolute proofs.

Contemporary information seeking increasingly presents challenges to automated verification systems, as a significant proportion of user queries center on claims that resist simple factual confirmation. Recent research indicates that only 64% of questions posed to information systems are directly verifiable through established sources; this represents a marked decline from the 96% direct verifiability rate observed in the widely used FEVER benchmark dataset. This shift suggests a growing demand for responses to subjective statements, forecasts about the future, or value-laden assertions-topics that, by their nature, exist outside the scope of purely empirical validation and require alternative approaches to responsible information provision.

Acknowledging the inherent limits of verifiability is paramount when constructing intelligent systems designed to address user queries. Rather than attempting to validate all claims as factual, effective systems must discern between those with empirical support and those rooted in opinion or prediction. This necessitates developing mechanisms for flagging unverifiable assertions, preventing the propagation of misinformation presented as fact. Furthermore, providing contextual information – such as identifying a statement as a prediction, an opinion, or a subjective judgment – enhances user understanding and promotes critical thinking. Ultimately, a nuanced approach to verifiability allows these systems to offer responsible and informative responses, even when faced with claims that fall outside the scope of empirical validation.

The study highlights a fundamental disconnect between the demand for fact-checking and the supply of verification resources. Users gravitate towards verifying easily observable claims-statements about what is directly visible or measurable. This preference suggests a pragmatic approach to truth-seeking, prioritizing immediate, demonstrable accuracy. As John McCarthy observed, “The best way to predict the future is to invent it.” This research doesn’t predict a future of sophisticated misinformation debunking; it reveals a present where users are attempting to build their own verification systems around simple, readily available data. The current emphasis on complex, sensationalized claims in benchmark datasets appears almost… quaint, given the observed user behavior. Systems, like fact-checking initiatives, must adapt to the reality of user needs if they wish to age gracefully.

The Grain of Truth

This analysis of what users actually want verified reveals a curious entropy at work. The system, as currently constructed, diligently catalogues the decay of complex claims – the elaborate fictions, the politically charged assertions. Yet, the demand – the logging of user behavior – consistently points toward simpler, more readily observable phenomena. It is as if the public seeks reassurance about the mundane, while the verification infrastructure focuses on arresting the spectacular. This mismatch isn’t a failure, merely a predictable consequence of differing timescales.

Future work must acknowledge this temporal friction. The creation of benchmark datasets, currently geared toward ambitious debunking, should incorporate a larger proportion of ‘low-hanging fruit’ – claims that, while seemingly trivial, represent the bulk of everyday verifiability needs. Furthermore, the field should investigate why this demand exists. Is it a fundamental human need for grounding in the observable world, or simply a reflection of cognitive biases? The answer, like all answers, will likely be both.

Ultimately, the pursuit of truth isn’t about halting decay, but understanding its pattern. Deployment of AI verification tools represents a single point on that timeline. The true challenge lies in building a system that gracefully ages alongside the evolving needs of those who seek its counsel – a system that acknowledges the difference between preserving a monument and maintaining a path.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.10935.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- MLBB x KOF Encore 2026: List of bingo patterns

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Married At First Sight’s worst-kept secret revealed! Brook Crompton exposed as bride at centre of explosive ex-lover scandal and pregnancy bombshell

- Top 10 Super Bowl Commercials of 2026: Ranked and Reviewed

- Why Andy Samberg Thought His 2026 Super Bowl Debut Was Perfect After “Avoiding It For A While”

- ‘Reacher’s Pile of Source Material Presents a Strange Problem

- How Everybody Loves Raymond’s ‘Bad Moon Rising’ Changed Sitcoms 25 Years Ago

- Genshin Impact Zibai Build Guide: Kits, best Team comps, weapons and artifacts explained

- Meme Coins Drama: February Week 2 You Won’t Believe

- February 12 Update Patch Notes

2026-02-13 01:57