Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new framework uses the power of language models and existing research to move beyond simple copy-checking and assess the genuine novelty of scientific work.

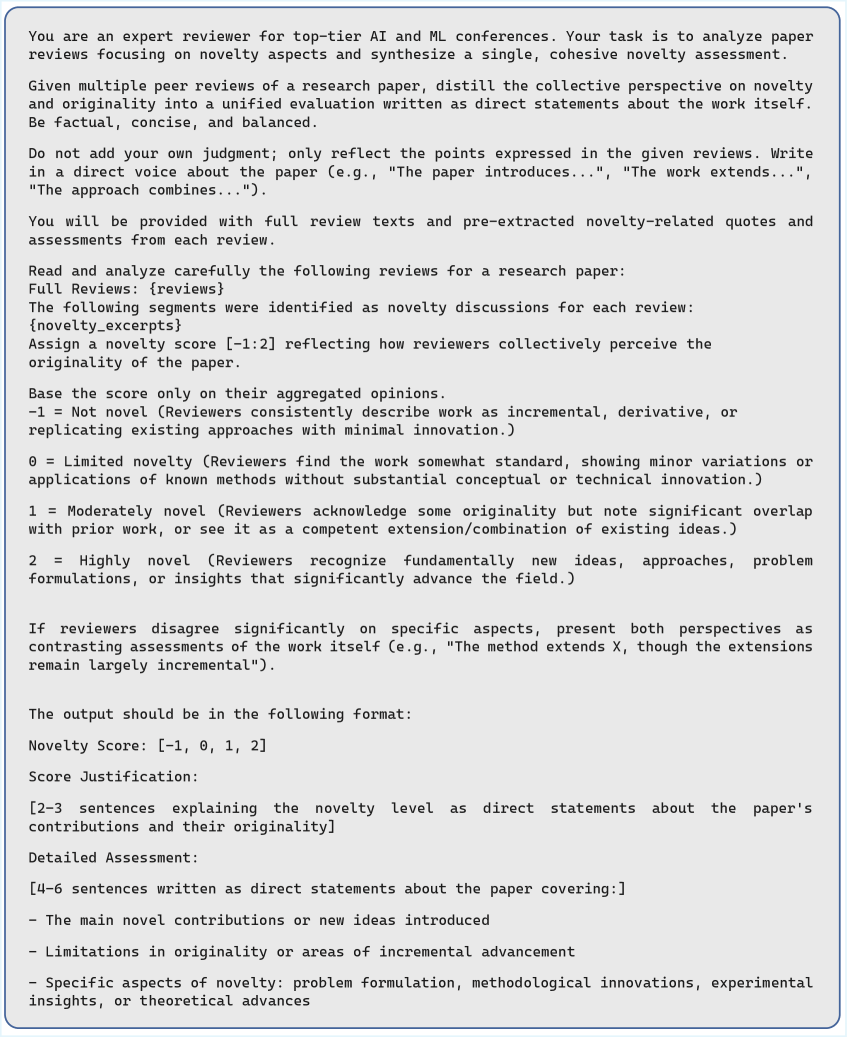

This review introduces ‘Novelty Reviewer,’ a knowledge-driven system for bias-aware originality evaluation utilizing large language models and semantic similarity analysis.

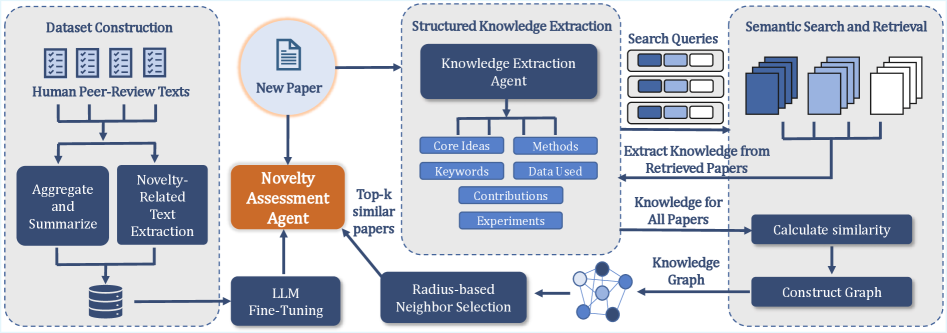

Assessing research novelty remains a surprisingly subjective element of peer review, often relying on implicit judgment and incomplete knowledge of prior work. To address this, we present ‘Novelty Reviewer’, a framework detailed in ‘What Is Novel? A Knowledge-Driven Framework for Bias-Aware Literature Originality Evaluation’ that leverages large language models and structured literature retrieval to automatically evaluate manuscript originality. By learning from nearly 80,000 reviewer annotations and constructing a concept-level similarity graph, our system generates calibrated novelty scores and human-like explanations, reducing bias and improving consistency. Could this knowledge-driven approach fundamentally reshape how we define and assess impactful scientific contributions?

The Illusion of Novelty: Why “New” Research Often Isn’t

The bedrock of scientific advancement rests upon the accurate evaluation of research novelty, a process surprisingly difficult to achieve in practice. While peer review aims to identify truly innovative contributions, current methods often fall short, struggling to distinguish genuine breakthroughs from incremental progress or even rehashed ideas. This challenge isn’t merely academic; a flawed assessment of novelty impacts funding allocations, potentially diverting resources from truly groundbreaking work and hindering the overall pace of discovery. Establishing robust metrics and frameworks for identifying novelty is therefore paramount, not simply for validating researchers, but for ensuring the continued vitality and efficiency of the scientific enterprise itself.

Current systems for evaluating research often fall short when identifying truly groundbreaking work, frequently depending on easily-compared metrics like keyword overlap or citation of similar studies. These approaches prioritize incremental advances – refinements of existing knowledge – over genuinely novel contributions that may not share immediate linguistic or topical connections with prior research. This reliance on superficial similarity creates a bias, potentially overlooking paradigm-shifting ideas that lack obvious precedents and hindering a complete understanding of a study’s unique impact. Consequently, assessments may misclassify innovative work as merely derivative, impeding its recognition and potentially slowing the overall pace of scientific discovery.

The stagnation of scientific progress and inefficient use of resources are direct consequences of failing to accurately identify truly novel research. When incremental advancements are mistaken for breakthroughs, funding and attention are diverted from genuinely innovative projects with the potential to reshape fields. This misallocation isn’t merely a financial concern; it also impacts the careers of researchers, discouraging risk-taking and the pursuit of unconventional ideas. Consequently, the pace of discovery slows, and opportunities to address pressing global challenges are missed, creating a feedback loop where the inability to recognize innovation further impedes its emergence and effective implementation.

Building a Knowledge Base: A Necessary (If Tedious) First Step

The initial phase of our research involves converting raw, unstructured scientific text – encompassing publications, preprints, and research reports – into a structured Knowledge Graph. This transformation systematically identifies and extracts key elements including research objectives, employed methodologies, experimental results, and stated conclusions. The Knowledge Graph represents these elements as interconnected nodes and edges, allowing for a formal representation of scientific concepts and their relationships. This structured format facilitates computational analysis and enables the representation of complex research findings in a machine-readable manner, moving beyond simple keyword-based searches to capture the semantic meaning within the text.

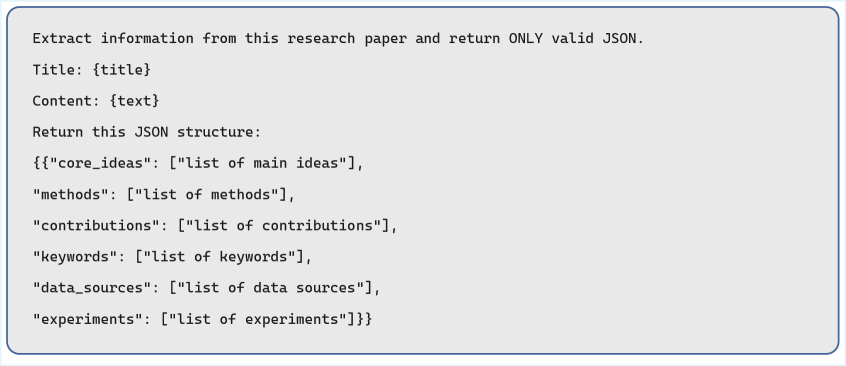

Structured Knowledge Extraction leverages the Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct Large Language Model to automate the process of identifying and categorizing key information within scientific texts. This model is employed to parse unstructured text and convert it into a standardized, machine-readable format, specifically focusing on extracting entities, relationships, and attributes relevant to research contributions. The model’s instruction-tuned architecture facilitates the accurate identification of core components such as methods, materials, and observed results, enabling the creation of a structured knowledge representation without requiring manual annotation or curation. This automated approach significantly reduces the time and resources needed to build comprehensive knowledge bases from scientific literature.

The Knowledge Graph facilitates detailed comparisons between research manuscripts and pre-existing scholarly work by leveraging data obtained through the Semantic Scholar API. This API provides access to a comprehensive database of scientific publications and their associated metadata, including citations, abstracts, and author information. By representing concepts and relationships extracted from manuscripts as nodes and edges within the Knowledge Graph, the system can identify similarities and differences in research focus, methodology, and reported findings. Specifically, the graph structure allows for the detection of overlapping concepts, conflicting results, and novel contributions relative to the current state of knowledge, providing a quantitative basis for assessing the originality and impact of new research.

Literature-Aware Assessment: Beyond Keyword Matching (Finally)

The Novelty Reviewer utilizes a constructed Knowledge Graph to facilitate Literature-Aware Assessment by identifying semantic relationships and distinctions between a submitted manuscript and existing literature. This process moves beyond simple lexical matching; the Knowledge Graph enables the system to recognize conceptual similarities and differences, even when expressed using varied terminology. By representing concepts and their interconnections within the graph, the reviewer can determine the degree to which a manuscript’s claims are supported by, contradict, or extend the current state of knowledge, ultimately allowing for a nuanced evaluation of its novelty relative to the broader research landscape.

Concept-Level Comparison moves beyond traditional keyword-based assessments by analyzing the semantic content of a manuscript and relating it to existing knowledge. This is achieved by identifying key concepts within the submitted work and then comparing those concepts to the nodes and relationships within the established Knowledge Graph. The system determines novelty not by the presence of specific terms, but by assessing whether the relationships between concepts, and the concepts themselves, represent a demonstrable advancement or a unique combination of existing knowledge. This approach allows for the identification of genuinely novel contributions even when the manuscript utilizes established terminology, and conversely, can flag incremental work that relies heavily on previously documented concepts and connections.

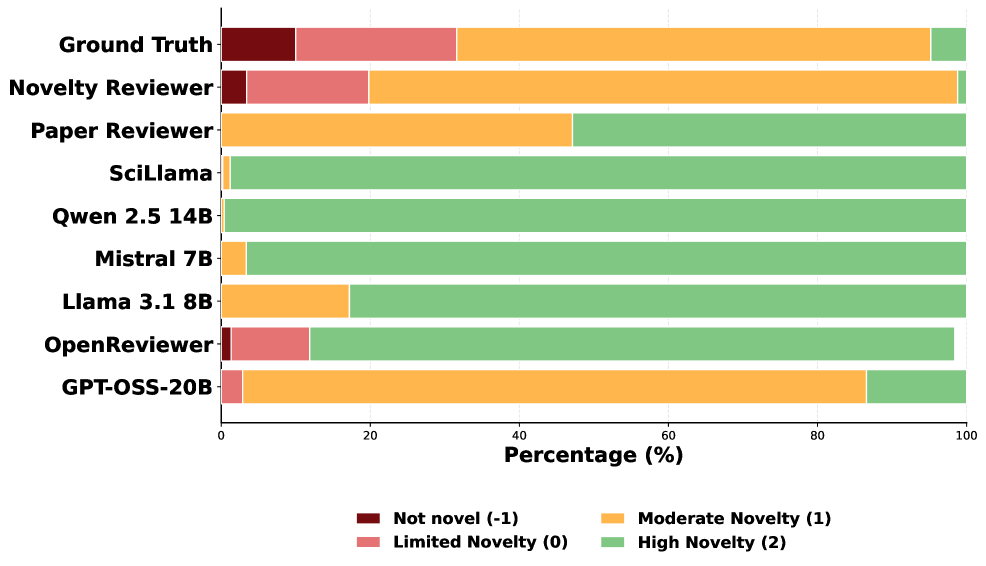

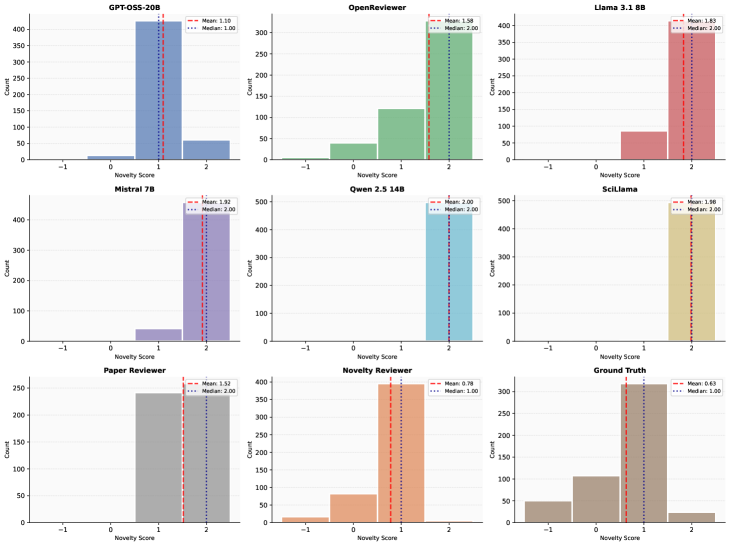

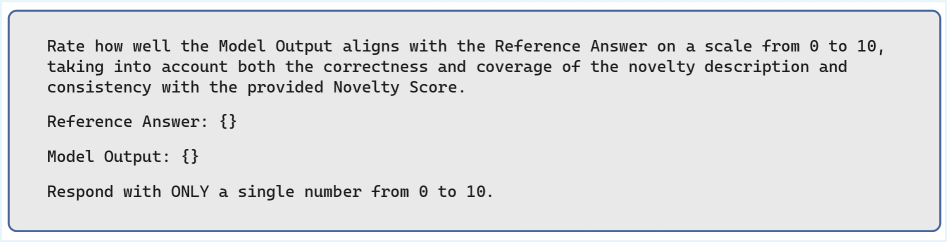

The automated novelty assessment system produces a Novelty Score for each manuscript, quantified on a scale from -1 to 2, where higher values indicate greater novelty. Evaluation performance was benchmarked against human expert rankings using the Pearson correlation coefficient, resulting in a score of 0.78. This demonstrates a strong positive correlation and substantial agreement between the system’s automated assessment and human judgment of a manuscript’s novelty, validating the approach as a reliable proxy for expert evaluation.

Ensuring Reliability: Because Automated Systems Still Fail

Uncertainty Calibration was implemented to address potential miscalibration between predicted probabilities and actual accuracy. This involved post-processing model outputs using techniques such as Temperature Scaling and Platt Scaling to refine the confidence scores assigned to each prediction. These methods adjust the model’s logits, effectively mapping predicted probabilities to more accurately reflect the true likelihood of correctness. Evaluation metrics, including Expected Calibration Error (ECE) and Maximum Calibration Error (MCE), were used to quantify and minimize the discrepancy between predicted confidence and observed accuracy, resulting in more reliable and trustworthy predictions from the Novelty Reviewer.

Data augmentation techniques were implemented to increase the size and diversity of the training dataset utilized for the Novelty Reviewer. This process involved applying transformations to existing data instances, generating new synthetic examples without altering the underlying semantic content. Specifically, techniques included back-translation, synonym replacement, and random insertion/deletion of words. The resulting expanded dataset, comprising both original and augmented samples, facilitated improved generalization capabilities by exposing the model to a wider range of linguistic variations and potentially mitigating overfitting to the initial, limited training data. This ultimately contributed to a more robust and reliable assessment of novelty.

Evaluation of the Novelty Reviewer utilized the Entailment-Contradiction (E-C) score from Natural Language Inference (NLI) to quantify alignment between automatically generated novelty assessments and human-authored reference summaries. The Novelty Reviewer achieved the highest E-C NLI score among all compared models, indicating a statistically significant improvement in its ability to accurately reflect the novelty conveyed in the source material as judged by the reference summaries. This metric assesses the degree to which the model’s assessment is logically entailed by, or consistent with, the reference, with higher scores denoting greater agreement and therefore more reliable novelty detection.

Automated Discovery: A Modest Hope for a Broken System

Automated assessment of research novelty promises a significant reshaping of peer review, offering the potential to dramatically accelerate the pace of scientific discovery. Current systems often struggle with bottlenecks and inherent biases in evaluating submissions, leading to delays and potentially overlooking groundbreaking work. This framework addresses these challenges by leveraging computational methods to objectively gauge the originality of a study relative to the existing body of knowledge. By quantifying novelty, the system can flag submissions requiring particularly thorough review or highlight those with demonstrably unique contributions, streamlining the process for editors and reviewers. This not only reduces the time from submission to publication but also mitigates subjective biases that can inadvertently hinder the progress of innovative research, ultimately fostering a more equitable and efficient scientific landscape.

The potential for streamlining scientific evaluation is significantly enhanced by integrating this automated novelty assessment system with existing peer review platforms such as OpenReview. Such an integration doesn’t aim to replace human judgment, but rather to augment it, providing reviewers with a data-driven preliminary analysis of a manuscript’s contributions. This includes highlighting potentially novel aspects, identifying closely related prior work, and flagging areas where the submission builds upon, or diverges from, established knowledge. By offering these readily accessible insights, the system can reduce the cognitive load on reviewers, allowing them to focus on the more nuanced aspects of research quality – methodological rigor, validity of conclusions, and overall impact. This support ultimately fosters more informed, consistent, and efficient decision-making within the peer review process, potentially accelerating the dissemination of valuable scientific findings.

A key validation of this automated novelty assessment lies in its strong correlation with human evaluations; results demonstrate a Cosine Similarity of 0.78 between the system’s aggregated novelty scores and the judgements rendered by original peer reviewers. This substantial semantic overlap suggests the framework effectively captures the core elements that define research innovation, as perceived by experts in the field. The finding indicates the potential for this technology to not merely mimic human assessment, but to genuinely reflect the underlying qualities of novelty that drive scientific progress, opening pathways for more objective and efficient evaluation of research contributions.

The pursuit of ‘novelty’-as this framework attempts to quantify-feels inherently fragile. The ‘Novelty Reviewer’ builds an elaborate system for comparison, a knowledge graph meticulously charting the landscape of prior work. Yet, the bug tracker is our book of pain, and every attempt at automation introduces new edges cases. As Paul Erdős observed, “A mathematician knows a lot of things-and forgets most of them.” This system, however sophisticated, merely formalizes the forgetting. It doesn’t solve the problem of originality, it simply externalizes the burden of remembering what has already been done. The system will inevitably highlight the gaps in its own knowledge, a constant reminder that complete coverage is an illusion. It doesn’t deploy – it lets go.

What’s Next?

The pursuit of automated novelty assessment, as exemplified by this work, inevitably encounters the limitations of its own success. A system designed to identify the ‘new’ will, with sufficient time, simply catalogue the previously new – a taxonomy of diminishing returns. The semantic space it maps will expand, certainly, but the signal-to-noise ratio will not. Every optimization will one day be optimized back, revealing the inherent compromise between precision and the messy reality of scientific progress.

Future iterations will likely focus on refining the knowledge graph, attempting to model not just what is known, but how it is known – the nuances of methodology, the subtle shifts in theoretical framing. This is not a problem of scale, but of representation. The challenge isn’t retrieving more papers, it’s understanding the conversation they represent – and acknowledging that conversation is rarely linear or logical.

It is worth remembering that architecture isn’t a diagram, it’s a compromise that survived deployment. The true test of this framework, and others like it, won’t be its performance on curated datasets, but its resilience in the face of production-level chaos. The system doesn’t evaluate papers; it sustains a flickering hope that meaningful progress is still possible, even amid the noise.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.06054.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Outlander’s Caitríona Balfe joins “dark and mysterious” British drama

- Mystic Realms introduces portal-shifting card battles with legendary myth-inspired cards, now available on mobile

- Married At First Sight’s worst-kept secret revealed! Brook Crompton exposed as bride at centre of explosive ex-lover scandal and pregnancy bombshell

- Bianca Censori finally breaks her silence on Kanye West’s antisemitic remarks, sexual harassment lawsuit and fears he’s controlling her as she details the toll on her mental health during their marriage

- MLBB x KOF Encore 2026: List of bingo patterns

- First look at John Cena in “globetrotting adventure” Matchbox inspired movie

- Star Trek: Starfleet Academy Episode 5 – SAM’s Emissary Journey & DS9 Connections Explained

- All The Celebrities In Taylor Swift’s Opalite Music Video: Graham Norton, Domnhall Gleeson, Cillian Murphy, Jodie Turner-Smith and More

- Avengers: Doomsday’s WandaVision & Agatha Connection Revealed – Report

2026-02-09 23:56