Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new framework combines the strengths of both optimization-based and analytic inverse kinematics to achieve more efficient and robust robotic motion planning.

This work presents a method for accelerating optimization-based inverse kinematics by utilizing analytic solutions as a variable transformation, reducing constraint complexity.

Despite decades of research, effectively combining the strengths of analytic and optimization-based approaches remains a central challenge in inverse kinematics. This paper, ‘A Framework for Combining Optimization-Based and Analytic Inverse Kinematics’, introduces a novel formulation that leverages analytic solutions as a change of variables within an optimization framework, simplifying the problem and improving solution robustness. Experimental results demonstrate significantly higher success rates across challenging robotic tasks-including collision avoidance and grasp planning-compared to existing methods. Could this approach unlock more reliable and efficient motion planning for complex robots operating in dynamic environments?

The Architecture of Motion: Defining Robotic Kinematics

A robot’s capacity for movement is fundamentally dictated by its kinematic structure, a blueprint of its physical configuration and the relationships between its joints. To precisely define this structure, engineers utilize the Denavit-Hartenberg (DH) parameters – a standardized set of four values assigned to each joint that describe its position and orientation relative to the preceding one. These parameters, typically expressed as distance, link twist, link length, and joint angle, create a mathematical framework enabling the calculation of the robot’s pose – its position and orientation in space – for any given set of joint angles. Through DH parameters, a complex robotic arm is broken down into a series of interconnected, precisely defined segments, allowing for accurate modeling, simulation, and control of its movements. The meticulous definition of kinematic structure is therefore the essential first step in unlocking a robot’s full potential and ensuring its ability to perform intended tasks within its operational limits.

Determining a robot’s capabilities hinges on understanding how joint movements translate into the position and orientation of its end-effector-a calculation known as forward kinematics. Utilizing parameters like link lengths and joint angles, this process effectively maps the robot’s internal configuration to its external behavior. Crucially, these kinematic calculations don’t just predict where the robot can reach, but define the entirety of its reachable workspace-the three-dimensional volume encompassing all possible end-effector positions. A robot’s workspace isn’t simply a matter of distance from its base; it’s shaped by the interplay of its joint limits and the geometry of its links, creating complex and often non-intuitive boundaries that dictate the tasks it can successfully perform. [latex] \theta_1, \theta_2, \dots, \theta_n [/latex] represent the joint angles used in these calculations, defining the robot’s pose.

Robots possessing more degrees of freedom than strictly necessary to perform a task – termed redundant manipulators – demonstrate the capacity for self-motion, a fascinating characteristic that simultaneously complicates and enriches motion planning. While traditional robots have a single solution for a given end-effector pose, redundant robots offer an infinite number, necessitating algorithms that optimize for secondary criteria beyond simply reaching the target. This optimization can prioritize avoiding obstacles, minimizing joint travel, maximizing manipulability-the robot’s ability to exert force in any direction-or even ensuring energy efficiency. However, exploiting this redundancy also introduces computational challenges; algorithms must navigate a vastly expanded solution space and account for singularities – configurations where the robot loses a degree of freedom. Consequently, advanced techniques like optimization-based planning and pseudo-inverse Jacobian methods are crucial for effectively harnessing the benefits of redundant kinematics, allowing these robots to perform complex maneuvers and adapt to dynamic environments with greater dexterity and robustness.

Ensuring Operational Integrity: Collision Avoidance Strategies

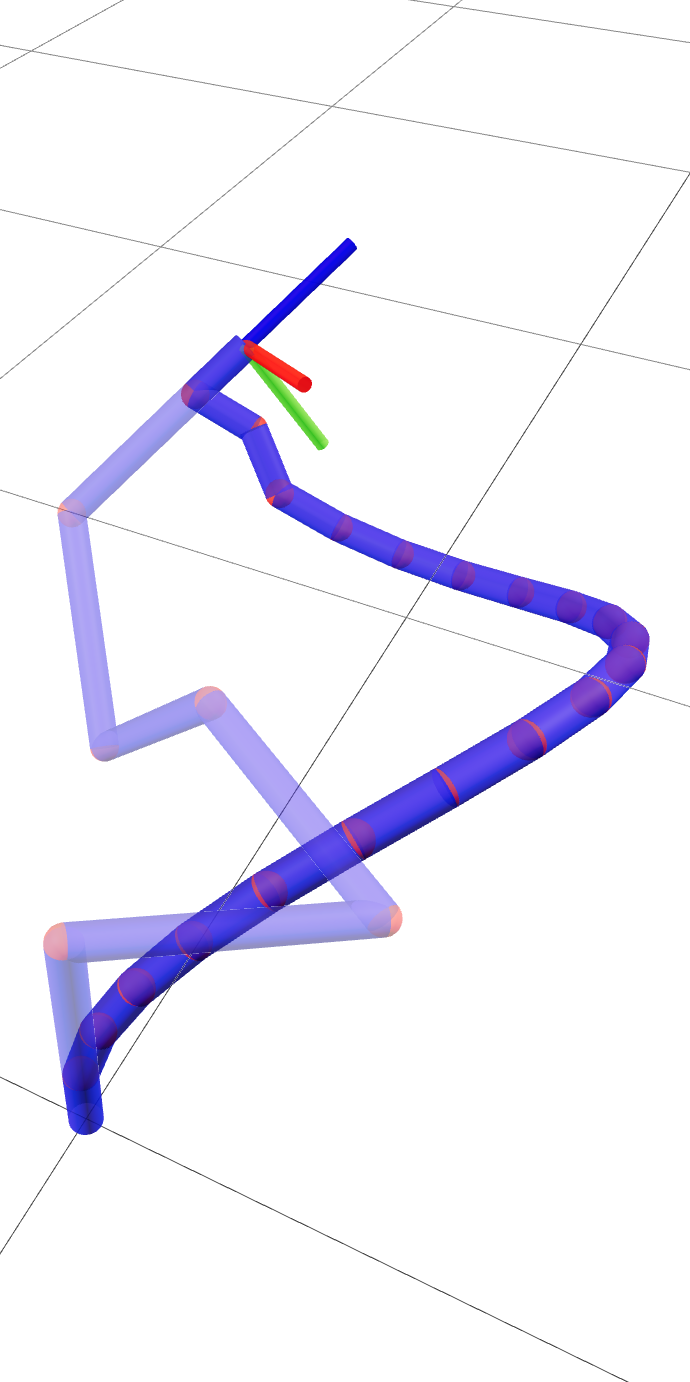

Effective collision avoidance is a foundational requirement for robotic systems operating in complex environments. The prevention of physical contact between the robot and its surroundings necessitates the implementation of reliable impact detection methods with minimal latency. These methods must account for the robot’s kinematics and dynamics, as well as the geometry of the environment, to accurately predict potential collisions before they occur. Failure to reliably detect and avoid collisions can result in damage to the robot, the environment, or harm to nearby humans, making robust collision avoidance critical for safe and dependable robotic operation. Proactive collision detection allows for timely adjustments to the robot’s trajectory, ensuring safe navigation and task completion.

Efficient collision detection often relies on simplified representations of robotic geometry. Convex hulls, the smallest convex set containing an object, provide a computationally inexpensive proxy for complex shapes, enabling rapid proximity checks. Signed distance fields (SDFs) further refine this approach by representing the distance to the nearest point on an obstacle’s surface, with the sign indicating whether a point is inside or outside the obstacle. Calculating the distance to the SDF value allows for determining penetration depth and the direction of the closest obstacle point. Utilizing these techniques reduces the computational burden of collision checks compared to analyzing the original, complex geometries, facilitating real-time obstacle avoidance in dynamic environments. [latex] SDF(x,y,z) = \min_{p \in obstacle} ||(x,y,z) – p|| [/latex]

The Clique Cover method facilitates proactive path planning by generating collision-free polytopes, which represent reachable, obstacle-free configurations for a robot. This technique decomposes the configuration space into a graph where nodes represent maximal collision-free sets – “cliques” – and edges connect overlapping cliques. By pre-computing these cliques and their connectivity, a path planner can efficiently search for a collision-free path through the graph, rather than performing real-time collision checking during motion execution. The size of the resulting graph is directly related to the complexity of the environment and the robot’s geometry; however, the pre-computation significantly reduces the computational burden during runtime, enabling faster and more reliable path planning in dynamic or cluttered environments. This approach is particularly effective in high-dimensional configuration spaces where traditional collision detection methods become computationally expensive.

From Desired Pose to Joint Command: Inverse Kinematics

Inverse Kinematics (IK) is the computational process of determining the set of joint angles necessary for a robotic manipulator to achieve a specified pose – position and orientation – of its end-effector. This is the inverse problem of forward kinematics, which calculates the end-effector pose given the joint angles. IK is fundamental to robotic control, allowing robots to interact with their environment in a purposeful manner; rather than specifying how a robot should move, IK defines where it should be, with the robot’s internal controllers computing the necessary joint trajectories. The desired pose is typically defined as a transformation matrix representing the end-effector’s position and orientation relative to a base coordinate frame. [latex] \mathbf{T} [/latex] represents this transformation, and the IK problem seeks to find the joint angle vector [latex] \mathbf{q} [/latex] such that the forward kinematics function [latex] f(\mathbf{q}) = \mathbf{T} [/latex].

Inverse Kinematics (IK) techniques encompass a spectrum of approaches differing in computational cost and solution guarantees. Analytic IK methods derive closed-form solutions, offering rapid computation of joint angles given an end-effector pose; however, these are limited to robot geometries where a mathematical solution exists. Optimization-based IK, conversely, formulates the problem as minimizing an error function representing the distance between the desired and actual end-effector pose. This allows for solutions on more complex robots but requires iterative numerical methods, increasing computational time. The choice between these methods depends on the specific application’s requirements for speed, accuracy, and the robot’s kinematic complexity.

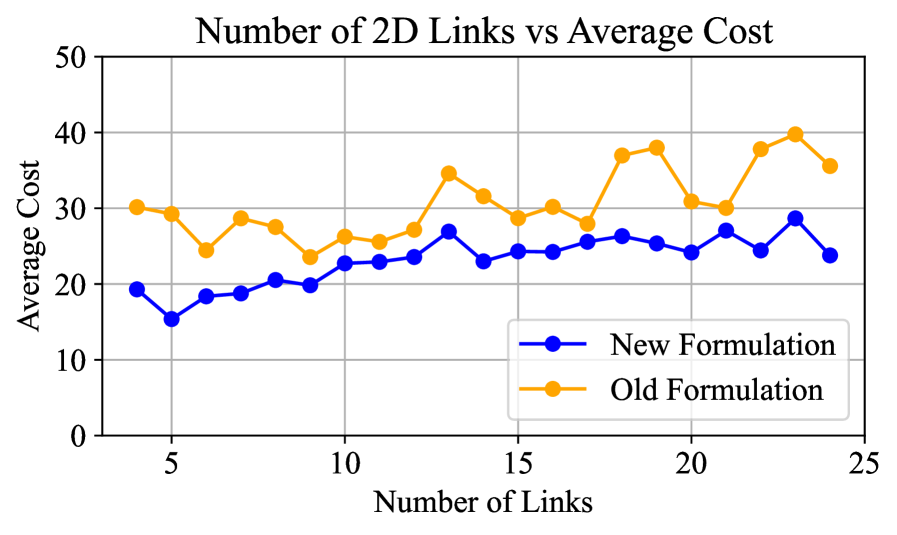

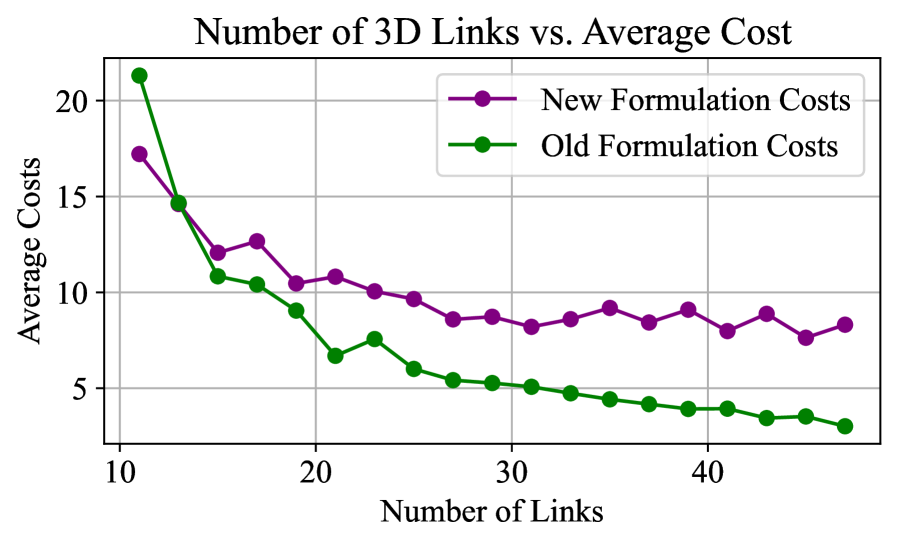

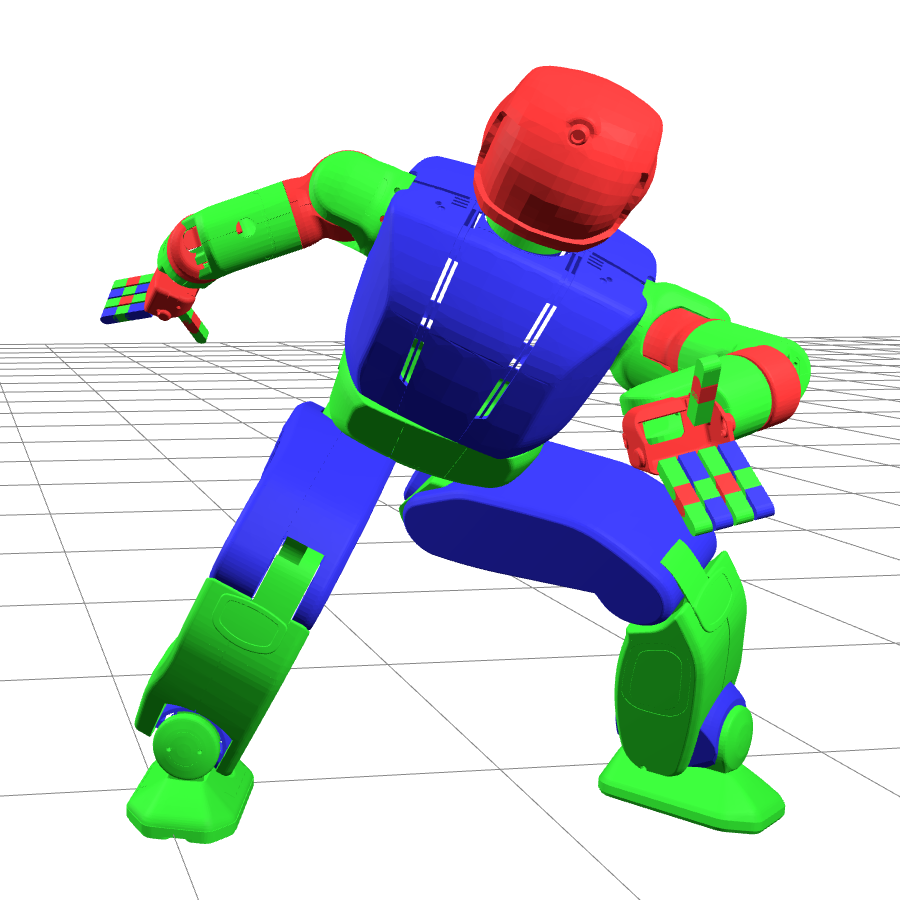

Inverse kinematics (IK) solvers utilize different approaches to determine joint angles corresponding to a desired end-effector pose. Analytic_IK methods provide rapid solutions via closed-form equations, but are limited to kinematic configurations where a solution can be directly calculated. Optimization-IK and Global_IK, conversely, formulate the IK problem as a convex optimization problem, allowing for more robust solutions, particularly in scenarios with complex constraints or redundancy. Recent advancements in optimization-based IK have demonstrated performance equal to or exceeding that of standard formulations across a range of robotic tasks, including arm manipulation on a table, grasp selection, bimanual manipulation, and humanoid stability control, indicating improved reliability and adaptability in diverse applications.

Constrained Motion: Stability and Operational Limits

Satisfying the demands of real-world robotic tasks requires careful attention to kinematic constraints – the physical limitations governing a robot’s movement. Constraint Inverse Kinematics (Constraint_IK) directly tackles the complex challenge of simultaneously meeting these limitations, which include the robot’s joint limits – the permissible range of motion for each joint – and crucial collision avoidance protocols. Without robust constraint handling, a robot might attempt to achieve a desired pose by exceeding its physical capabilities or by colliding with its environment. Constraint_IK methodologies aim to calculate valid joint configurations that not only reach the target position but also remain within these safe and feasible boundaries, ensuring smooth, predictable, and damage-free operation even in cluttered or dynamically changing scenarios.

Maintaining a stable pose is paramount for robotic operation, and stability constraints are integral to achieving this throughout a task. These constraints don’t simply prevent toppling; they actively shape the robot’s motion to ensure its center of mass remains within its support polygon – the area defined by its contact points with the environment. Without such constraints, even seemingly minor movements could lead to instability, especially when dealing with dynamic motions or uneven terrain. Incorporating stability directly into the robot’s motion planning process allows it to proactively adjust its trajectory, preemptively counteracting potential disturbances and guaranteeing a secure and predictable stance. This is achieved by formulating stability as a mathematical constraint within the optimization problem used to calculate the robot’s movements, effectively guiding it towards poses and trajectories that inherently resist destabilizing forces.

Safe, reliable, and predictable robotic operation hinges on effectively managing a multitude of kinematic constraints. Recent advances in constraint-based inverse kinematics offer improved performance in this critical area, allowing robots to operate closer to their physical limits without compromising stability. This is achieved through a simplified optimization landscape, which facilitates the imposition of even complex constraints – such as maintaining a stable center of gravity during dynamic movements – with greater precision. Consequently, robots can navigate challenging environments and execute intricate tasks while adhering to stringent safety requirements and demonstrating consistently predictable behavior, ultimately broadening their potential applications in fields ranging from manufacturing to healthcare.

The presented framework deftly addresses the inherent complexity within inverse kinematics, recognizing that a system’s behavior is fundamentally dictated by its structure. This echoes Andrey Kolmogorov’s observation: “The most important things are the ones you don’t know.” The research illuminates how cleverly restructuring the optimization problem – by employing analytic IK as a change of variables – effectively reduces the constraint space. This isn’t merely a computational shortcut; it’s a demonstration of how understanding the underlying structure allows for a more elegant and efficient solution. Every new dependency, as the paper implicitly suggests, is the hidden cost of freedom; simplifying the structure unlocks performance gains by minimizing those hidden costs. The approach champions clarity and simplicity as pathways to robust robotic control.

Where Do We Go From Here?

The presented work addresses a persistent tension in robotic control: the desire for both the speed of analytic solutions and the generality of optimization. By framing optimization-based inverse kinematics as a change of variables, the authors sidestep, rather than solve, the fundamental problem of ill-conditioning. This is not a failing, but a recognition that true robustness emerges from reducing the search space, not from cleverly navigating a complex one. The efficacy of this approach hinges, naturally, on the availability of suitable analytic solutions – a limitation that will become more acute as robot designs move beyond simple serial architectures.

Future work must confront the fact that analytic solutions, while fast, are brittle. The elegance of a closed-form solution masks an underlying rigidity; a small deviation from the idealized model, and the entire structure falters. The real challenge lies not in finding better optimizers, but in developing representations that gracefully degrade. Perhaps the most fruitful avenue lies in exploring hybrid approaches-analytic solutions as initial guesses, refined through optimization, and continually validated by sensory feedback. The cost of freedom, after all, is not computation, but adaptation.

Ultimately, the field needs to move beyond the pursuit of ‘optimal’ solutions and focus on ‘sufficient’ ones. A system’s true complexity is not in its calculations, but in its ability to function reliably in an unpredictable world. Good architecture, as ever, is invisible until it breaks – and the breaking point reveals the assumptions hidden within the design.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.05092.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Outlander’s Caitríona Balfe joins “dark and mysterious” British drama

- Bianca Censori finally breaks her silence on Kanye West’s antisemitic remarks, sexual harassment lawsuit and fears he’s controlling her as she details the toll on her mental health during their marriage

- Married At First Sight’s worst-kept secret revealed! Brook Crompton exposed as bride at centre of explosive ex-lover scandal and pregnancy bombshell

- MLBB x KOF Encore 2026: List of bingo patterns

- Wanna eat Sukuna’s fingers? Japanese ramen shop Kamukura collabs with Jujutsu Kaisen for a cursed object-themed menu

- Bob Iger revived Disney, but challenges remain

- First look at John Cena in “globetrotting adventure” Matchbox inspired movie

- Mystic Realms introduces portal-shifting card battles with legendary myth-inspired cards, now available on mobile

- How TIME’s Film Critic Chose the 50 Most Underappreciated Movies of the 21st Century

2026-02-09 05:25