Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new evaluation benchmark reveals that current language models often fail to adequately explore interactive environments, leading to suboptimal decisions and a lack of adaptability.

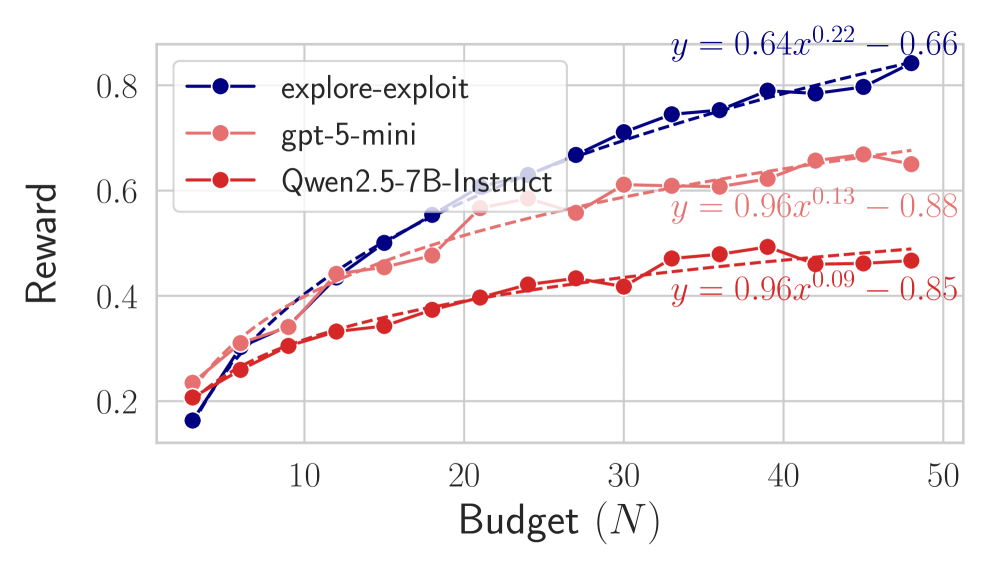

![Across all evaluated tasks, explore-exploit baselines consistently surpassed the performance of language models when operating under a query budget of [latex]N=48[/latex], demonstrating robustness to variations in parameter settings.](https://arxiv.org/html/2601.22345v1/x72.png)

The study demonstrates a significant deficiency in exploration versus exploitation strategies within budgeted interactive tasks, highlighting a critical gap in agentic AI development.

Despite advances in agentic AI, language models often struggle to effectively gather information in dynamic environments. This limitation is explored in ‘Failing to Explore: Language Models on Interactive Tasks’, which introduces a benchmark for evaluating exploration in budgeted interactive settings. The study reveals that state-of-the-art models systematically under-explore, yielding suboptimal solutions even when compared to simple heuristics. Can lightweight interventions, such as parallel execution or interaction summarization, unlock more effective exploration strategies for language-based agents and realize their full potential in complex, interactive tasks?

The Challenge of Sparse Rewards

For an agent to master complex tasks, effective exploration of its environment is paramount, yet this presents a significant challenge when rewards are infrequent or delayed – a situation known as a sparse reward landscape. In such scenarios, an agent may wander aimlessly for extended periods without receiving any positive reinforcement, hindering its ability to learn optimal strategies. This is because traditional reinforcement learning algorithms often rely on frequent rewards to guide the learning process; without them, the agent struggles to differentiate between beneficial and detrimental actions. Consequently, developing methods that enable robust exploration in sparse reward environments is a critical area of research, paving the way for more adaptable and intelligent agents capable of tackling real-world problems where immediate gratification is rarely guaranteed.

Despite the current enthusiasm surrounding Large Language Models (LLMs), research consistently reveals that surprisingly simple exploration algorithms – such as the Explore-Exploit Baseline – demonstrate superior performance in complex environments. Across a diverse range of tasks and varying computational budgets, these baseline algorithms consistently outperform LLMs, achieving greater efficiency in navigating sparse reward landscapes. This isn’t to suggest LLMs have no role, but rather highlights that effective exploration isn’t necessarily reliant on complex architectures or massive datasets. The robustness of these simple algorithms suggests that fundamental principles of balancing exploration and exploitation remain critical for successful agent learning, even as more sophisticated techniques emerge.

Strategic Exploration Through Language

Language models (LLMs) offer potential improvements to exploration in complex search spaces due to their inherent capabilities in natural language processing. Unlike traditional algorithms relying on pre-defined rules or heuristics, LLMs can interpret high-level, descriptive instructions specifying desired behaviors or goals. This allows for the formulation of exploration strategies based on qualitative guidance, rather than quantitative parameters. Furthermore, LLMs, particularly those with large parameter counts, demonstrate the capacity to generate a wider range of diverse strategies compared to conventional methods, potentially escaping local optima and accelerating the discovery of effective solutions in environments where exhaustive search is impractical. This strategic diversity arises from the probabilistic nature of LLM text generation, allowing for the consistent production of varied, yet potentially viable, exploratory actions.

Current research demonstrates the application of Large Language Models (LLMs) to various search algorithms, notably HillSearch, TreeSearch, and MaxSatSearch. In these implementations, LLMs function as agents that actively query an environment – which could be a simulated game state or a computational problem instance – to obtain reward signals. These rewards are then used to iteratively refine the agent’s search strategy; the LLM analyzes the feedback and adjusts its subsequent queries to maximize cumulative reward. This process necessitates the LLM’s ability to interpret environment states, formulate actions based on those states, and learn from the resulting rewards, effectively implementing a reinforcement learning loop within the LLM’s generative process.

The efficacy of Language Model (LLM)-based agents in search and problem-solving tasks is fundamentally dependent on the design of the reward function used to evaluate performance. LLMs operate by maximizing cumulative reward, meaning the reward function directly shapes the agent’s learned behavior and ultimately determines task success. A poorly defined reward function-one that is ambiguous, sparse, or misaligned with the desired outcome-can lead to suboptimal strategies, unintended consequences, or even failure to learn. Therefore, careful consideration must be given to the precision, completeness, and accuracy of the reward function during task design, as it serves as the primary feedback mechanism guiding the LLM’s exploration and refinement of its search process.

![The model navigates partially observed environments-including function optimization ([latex]f(x)[/latex]), tree searching with deceptive rewards, and MaxSat problems with hidden critical clauses-under a budget, requiring a balance between exploration and exploitation to avoid suboptimal solutions and identify optimal strategies.](https://arxiv.org/html/2601.22345v1/x1.png)

Targeted Interventions for Enhanced Exploration

Parallel threads represent an exploration strategy where the total interaction budget is distributed across multiple independent searches, rather than concentrated on a single trajectory. This approach increases exploration breadth by simultaneously pursuing diverse lines of inquiry. Each thread operates as a separate search process, allowing the model to investigate a wider range of potential solutions concurrently. By diversifying the search space in this manner, parallel threads can potentially uncover solutions that might be missed by a single, focused search, especially in complex or multi-modal problem domains. The effectiveness of this method relies on an appropriate allocation of the interaction budget across the threads to balance breadth and depth of exploration.

Periodic Summarization addresses the context window limitations of Large Language Models (LLMs) during extended exploration tasks. By condensing the history of interactions into a shorter, summarized form at regular intervals, the LLM can retain crucial information without exceeding its input capacity. This summarized history is then prepended to the current prompt, allowing the model to reference previous steps and maintain a consistent trajectory during exploration. The technique facilitates more informed decision-making and prevents the LLM from losing track of earlier discoveries, ultimately enhancing the effectiveness of its search process.

Evaluations demonstrate that both parallelization, through the use of multiple independent searches, and periodic summarization, which provides a condensed interaction history to the LLM, consistently yield performance improvements across various tasks. However, despite these gains, neither technique fully matches the efficacy of simpler Explore-Exploit baselines, indicating a remaining performance gap. This suggests that further research and optimization are necessary to maximize the benefits of these targeted interventions and achieve comparable or superior results to established exploration strategies. Ongoing development should focus on refining the implementation of parallelization and summarization, as well as exploring potential synergistic effects when combined.

![Across variations in task difficulty-controlled by parameters like peak width for HillSearch, gateway ratios for TreeSearch, and gold clause size for MaxSatSearch-parallel and summary methods consistently enhance the performance of Qwen2.5-7B-Instruct, bringing it closer to simple explore-exploit baselines with a budget of [latex]N=36[/latex].](https://arxiv.org/html/2601.22345v1/x69.png)

Resource Allocation: The Key to Agent Performance

The success of both Large Language Model (LLM) and traditional Explore-Exploit agents hinges significantly on how effectively their limited interaction budget is allocated. A judicious budget strategy isn’t simply about minimizing cost; it’s about achieving a delicate balance between breadth – the scope of the search space explored – and depth – the intensity of investigation within promising areas. Insufficient budgeting restricts an agent’s ability to thoroughly investigate potentially optimal solutions, while excessive focus on a narrow subset can lead to overlooking superior alternatives. This interplay directly influences performance in complex environments, as agents must continually assess whether to broaden their search for novel approaches or refine existing strategies – a decision profoundly shaped by the available resources and their careful distribution.

Effective resource allocation is paramount when designing intelligent agents operating within constrained environments. A carefully considered budget strategy doesn’t simply limit an agent’s actions; it fundamentally shapes how it searches for solutions. By intelligently distributing limited interaction resources – be it computational steps, API calls, or experimental trials – an agent can prioritize promising avenues of exploration while avoiding wasteful redundancy. This focused approach maximizes the potential for discovering optimal solutions, even with a restricted budget. The agent’s ability to balance broad exploration of the solution space with focused exploitation of known good options is directly tied to this budgetary framework, ensuring that every interaction contributes meaningfully to the overall learning process and ultimately boosts performance.

Research consistently reveals a surprising outcome: Large Language Models (LLMs), despite their sophisticated architecture, frequently underperform simpler Explore-Exploit baseline agents when tasked with complex problem-solving. This isn’t a matter of inherent capability, but rather one of resource management; LLMs often inefficiently allocate their interaction resources, leading to suboptimal search strategies. The consistent outperformance of these baselines across diverse tasks highlights a crucial point: in complex search environments, the way an agent utilizes its limited resources is often more important than the sheer power of its underlying model. This underscores the need for novel approaches to budget allocation and interaction strategies specifically designed to maximize the efficiency of LLMs, allowing them to truly leverage their potential.

![Across 18 MaxSatSearch episodes with a budget of [latex]N=48[/latex], Qwen2.5-7B-Instruct frequently makes single-flip local changes, sometimes prematurely halting exploration after finding a high reward, while the explore-exploit baseline generally identifies a good assignment early on and refines it with local search.](https://arxiv.org/html/2601.22345v1/x66.png)

The study illuminates a critical failing in current language models: a premature commitment to solutions without sufficient exploration of the interactive environment. This echoes Alan Turing’s sentiment: “Sometimes people who are unaware that their feelings are mixed will act as though they are less complex than they are.” The models, much like individuals masking internal complexity, quickly settle on an initial path, failing to adequately probe for superior alternatives. The research demonstrates that a lack of robust exploration strategies hinders these agents from achieving optimal results, reinforcing the need for systems capable of embracing uncertainty and systematically investigating possibilities before committing to a course of action. This inability to delay gratification and seek a more complete understanding parallels a fundamental limitation in artificial intelligence.

The Road Ahead

The presented work distills a simple, yet persistent, failing: current language models, when tasked with agency, prioritize immediate gratification over diligent search. The benchmark isn’t a measure of intelligence, but of a particularly human impatience. The focus, predictably, falls on exploitation – committing to a path, however flawed, rather than incurring the cost of continued inquiry. This isn’t a bug, it is, perhaps, a feature of systems trained on static datasets, where the illusion of omniscience is easily maintained.

Future efforts should not concern themselves with elaborate architectures, but with parsimonious incentives. The problem isn’t can these models act, but why they choose not to fully investigate. Evaluation must move beyond simple reward maximization and incorporate metrics for epistemic humility – a quantifiable measure of ‘not knowing’, and the willingness to address it.

Ultimately, the challenge isn’t building agents that appear intelligent, but systems that acknowledge the inherent limits of their knowledge. The most fruitful avenues of inquiry will likely lie not in adding complexity, but in rigorously subtracting unnecessary assumptions, and accepting that the value resides not in the solution found, but in the thoroughness of the search.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.22345.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Wanna eat Sukuna’s fingers? Japanese ramen shop Kamukura collabs with Jujutsu Kaisen for a cursed object-themed menu

- Bob Iger revived Disney, but challenges remain

- First look at John Cena in “globetrotting adventure” Matchbox inspired movie

- Outlander’s Caitríona Balfe joins “dark and mysterious” British drama

- Mystic Realms introduces portal-shifting card battles with legendary myth-inspired cards, now available on mobile

- How TIME’s Film Critic Chose the 50 Most Underappreciated Movies of the 21st Century

- Jacobi Elordi, Margot Robbie’s Wuthering Heights is “steamy” and “seductive” as critics rave online

- Avengers: Doomsday’s WandaVision & Agatha Connection Revealed – Report

- TOWIE’s Elma Pazar stuns in a white beach co-ord as she films with Dani Imbert and Ella Rae Wise at beach bar in Vietnam

2026-02-08 14:04