Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research sheds light on the inner workings of the ESMFold model, revealing the computational steps behind its remarkable ability to predict protein structures.

A two-stage mechanism is identified within ESMFold, where initial layers process biochemical information and subsequent layers refine geometric relationships to accurately predict protein folding.

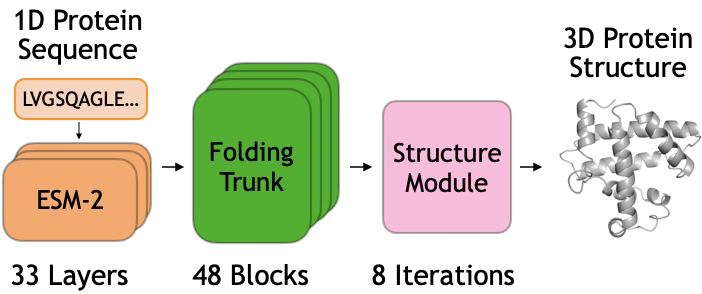

Despite recent advances in de novo protein structure prediction, the computational mechanisms driving these models remain largely opaque. This research, titled ‘Mechanisms of AI Protein Folding in ESMFold’, investigates how the ESMFold model folds proteins by tracing information flow through its internal representations. We demonstrate a two-stage process where initial blocks propagate biochemical signals derived from sequence, and subsequent blocks refine spatial relationships, culminating in a predicted structure. Understanding these localized mechanisms-and the potential for their manipulation-could unlock new strategies for protein design and engineering.

The Folding Prophecy: Decoding Protein Architecture

Determining a protein’s three-dimensional structure from its amino acid sequence has long been a pivotal, yet remarkably difficult, goal in computational biology. Proteins don’t function in isolation; their activity is intimately linked to their precise shape, which dictates how they interact with other molecules. However, the sheer number of possible configurations a protein chain can adopt – a space known as conformational space – is astronomically large, making traditional prediction methods computationally prohibitive. While the sequence of amino acids contains all the information needed to define the structure, deciphering this ‘folding code’ requires navigating a complex energy landscape, where even subtle changes in the sequence can dramatically alter the final folded state. Consequently, accurately predicting structure remains a major bottleneck in understanding biological processes and designing new therapeutics, driving continued innovation in this critical field.

Predicting a protein’s ultimate three-dimensional form is immensely difficult because the process navigates an extraordinarily complex ‘energy landscape’. Imagine a rugged terrain with countless peaks and valleys; the protein seeks the lowest energy state, but finding it requires searching an almost infinite number of possible shapes – the ‘conformational space’. Traditional computational methods, relying on physics-based simulations, often get trapped in local energy minima, mistaking them for the true, stable structure. This is akin to a hiker settling for a small dip in the land instead of the deepest valley. The sheer scale of this search problem – the number of possible conformations grows exponentially with the protein’s length – renders many conventional approaches computationally intractable, hindering progress in understanding protein function and designing new therapeutics.

ESMFold represents a significant advancement in protein structure prediction by employing a deep learning framework that directly outputs three-dimensional coordinates. Unlike traditional methods that often navigate complex energy landscapes and vast conformational spaces, ESMFold bypasses these computational bottlenecks. The model achieves this by learning directly from the relationships between amino acid residues-specifically, it predicts residue identity with up to 70% accuracy based on pairwise features. This direct coordinate prediction, coupled with its high accuracy in discerning residue relationships, allows for a substantially faster and more efficient determination of protein structure, opening new avenues for understanding protein function and accelerating drug discovery efforts.

![The rate of structural convergence, measured by [latex]Cα_{RMSD}[/latex] to the highest-recycle ESMFold prediction, decreases rapidly for short proteins within the first recycle but continues to improve substantially with additional refinement cycles for longer proteins.](https://arxiv.org/html/2602.06020v1/Figures/recycle_plot.png)

The Refinement Engine: Building the Folding Trunk

The ‘Folding Trunk’ architecture employs an iterative refinement process that operates on two complementary representations of a protein: the sequence and a pairwise representation. This process isn’t a simple linear progression; rather, information is exchanged between these representations across multiple blocks. Each block refines both the understanding of the amino acid sequence and the predicted spatial relationships between residues. This iterative cycle allows the model to progressively improve the accuracy of the protein structure prediction by continually incorporating information from both sources of data, leading to a more consistent and accurate final fold.

The ESMFold architecture employs two primary pathways – Sequence-to-Pair (Seq2Pair) and Pairwise-to-Sequence (Pair2Seq) – to enable reciprocal information transfer between the protein’s sequence and pairwise representations. Seq2Pair transforms the one-dimensional sequence information into a two-dimensional pairwise representation, effectively predicting residue-residue distances and relationships. Conversely, Pair2Seq reconstructs sequence information from the pairwise representation, allowing the model to refine its understanding of the sequence based on the established spatial constraints. This iterative exchange, occurring within each block of the network, ensures consistent information flow and mutual refinement of both representations throughout the folding process.

ESMFold’s iterative refinement process is critical for accurately predicting protein structures by capturing long-range dependencies between amino acids. This is achieved through successive blocks, where information is exchanged between sequence and pairwise representations, progressively refining the predicted structure. Analysis indicates that complete transfer of sequence information-meaning all residues have informed their spatial relationships-is demonstrably achieved by block 15, after which further iterations yield diminishing returns in prediction accuracy. This efficient information propagation allows ESMFold to model complex folding patterns reliant on distant interactions within the protein.

The pairwise representation within ESMFold functions as a distance map, explicitly encoding the spatial relationships between amino acid residues. This map details the Euclidean distances between all residue pairs, providing a comprehensive geometric description of the protein structure. Rather than directly predicting coordinates, the model learns to predict these inter-residue distances, which are then used to reconstruct the three-dimensional conformation. This approach allows ESMFold to efficiently capture and represent the complex spatial constraints necessary for accurate protein folding, as distances are less susceptible to rotational and translational ambiguities compared to direct coordinate prediction.

From Representation to Geometry: The Structure Module’s Decree

The Structure Module functions as the final stage in translating learned representations into geometrically defined structures. It takes as input the refined sequence and pairwise relationship data generated by preceding modules and utilizes this information to predict 3D coordinates for each residue. This conversion process effectively maps the abstract, relational understanding of the protein into a concrete spatial arrangement. The output of the Structure Module is a set of [latex] (x, y, z) [/latex] coordinates representing the predicted atomic positions, which can then be evaluated for biophysical plausibility and accuracy using established structural metrics.

Invariant Point Attention (IPA) is a mechanism within the Structure Module designed to refine 3D coordinate prediction by dynamically weighting relationships between points. Unlike standard attention which considers all pairwise relationships equally, IPA specifically focuses on identifying and emphasizing geometrically crucial interactions. This is achieved by learning to attend to points that are spatially relevant to each other during the coordinate refinement process, effectively prioritizing the maintenance of correct relative positioning. The attention weights are determined by a learned function of the pairwise distances and orientations between points, allowing the model to implicitly encode geometric constraints and improve the accuracy and physical plausibility of the predicted 3D structures.

The quality of predicted 3D structures is evaluated using the Radius of Gyration (Rg), a metric quantifying the compactness of the structure. Rg is calculated as the root-mean-square distance of each atom from the center of mass. To differentiate between meaningful compaction and nonspecific collapse, a threshold of 0.7 is applied to the calculated Rg value; structures falling below this threshold are excluded from further analysis, indicating an unrealistically compact conformation. This filtering step ensures that only structures exhibiting a reasonable degree of spatial extension are considered valid predictions.

To evaluate the quality of the learned representations, linear probes are utilized as a diagnostic tool. These probes are trained to predict linear distances between residue pairs based on the encoded representations. A high R2 score of 0.9 is consistently achieved with these linear distance probes, indicating that the representations effectively encode information necessary for accurate distance prediction. This metric demonstrates the accessibility of spatial information within the learned feature space, validating the effectiveness of the representation learning process.

![Linear probes reveal that charge information is initially accessible in pairwise representations ([latex] \text{seq2pair} [/latex]), transferring through early blocks before becoming progressively transformed into more geometric features in later blocks as the trunk transitions to stage 2 computation, as indicated by declining probe accuracy.](https://arxiv.org/html/2602.06020v1/Figures/AppendixFigureChargeProbing1.png)

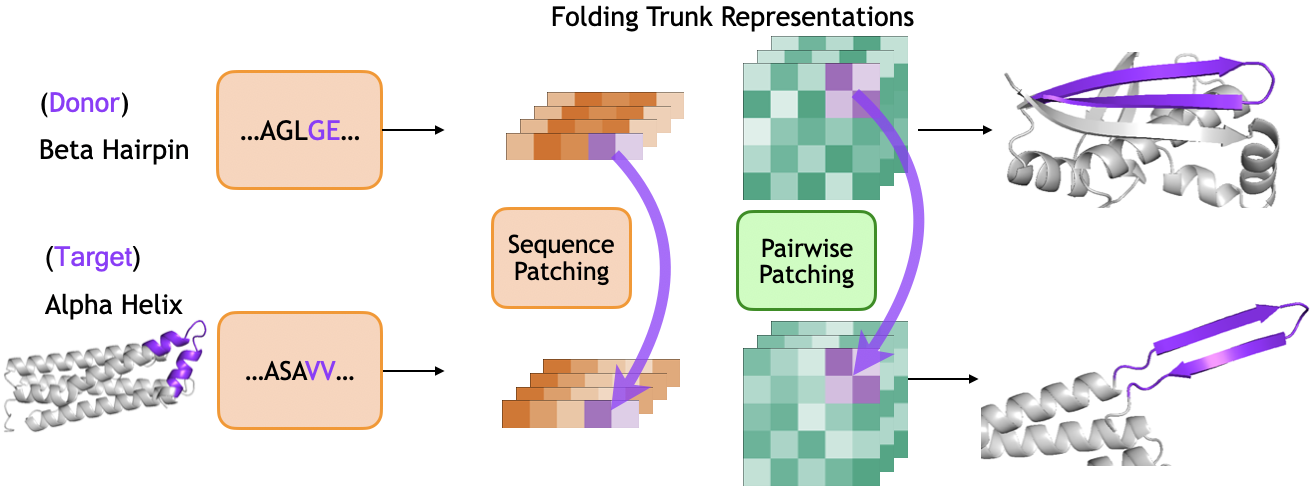

The Echo of Causality: Activation Patching and the Prophecy Fulfilled

Activation patching represents a novel technique allowing researchers to dissect the complex process of protein folding by transplanting learned structural representations between different proteins. This approach moves beyond simple observation, enabling a form of causal analysis where the influence of specific structural elements can be directly tested. By ‘patching’ a representation associated with folding in one protein onto another, scientists can determine if that element is sufficient to induce similar folding behavior – essentially asking if a particular structural feature causes a specific fold. This isn’t merely about predicting structure; it’s about understanding how proteins fold, offering insights into the underlying biophysical principles and validating whether a model has truly learned the rules governing protein architecture, rather than simply memorizing known structures.

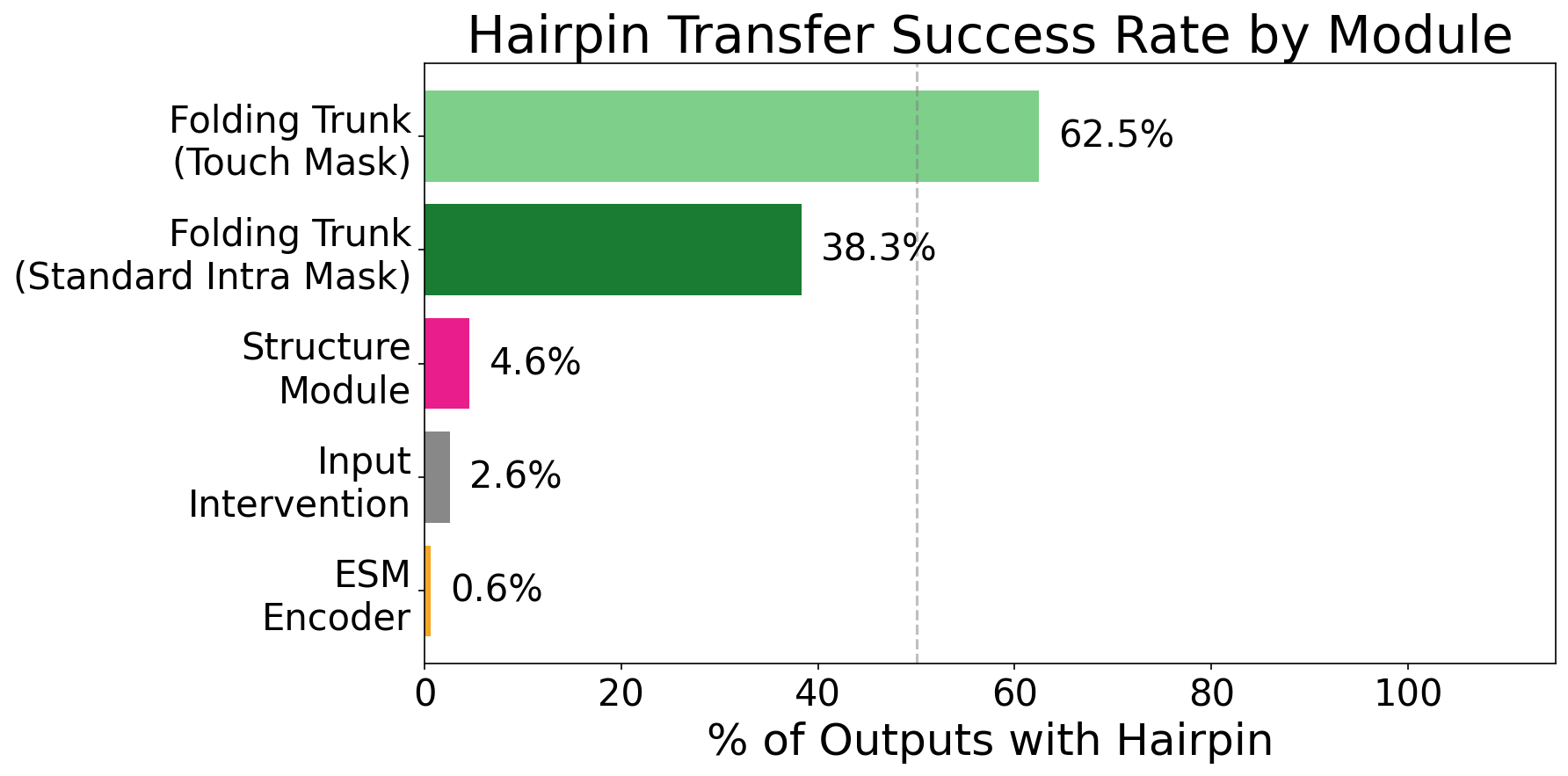

Researchers are leveraging the predictable folding patterns of simplified protein elements, specifically beta hairpins, to rigorously test the underlying principles captured within the ESMFold model. These small, structurally defined motifs offer a controlled environment for analysis; if the model accurately understands how proteins achieve stability, it should consistently predict correct hairpin folding. By systematically challenging ESMFold with variations in hairpin sequence and environmental conditions, scientists can discern whether the model is merely recalling memorized structures or genuinely applying learned rules of protein physics. Successful prediction of hairpin folding, therefore, serves as a critical benchmark, demonstrating that the model has internalized fundamental structural principles rather than simply acting as a complex lookup table.

The inherent stability of beta hairpins, fundamental building blocks in protein structure, arises demonstrably from a principle known as electrostatic complementarity between constituent amino acid residues. Researchers found that favorable interactions – specifically, the attraction between oppositely charged residues and the avoidance of like-charged residues – are key determinants of hairpin folding. This isn’t merely correlation; the model accurately predicts and reproduces hairpin stability based on these electrostatic forces. This capability showcases the model’s ability to move beyond simple structural memorization and instead capture the underlying biophysical principles governing protein folding – a critical step towards truly understanding and predicting protein behavior.

Recent analysis demonstrates that ESMFold’s proficiency extends beyond mere structural memorization; the model actively learns the underlying principles governing protein folding. This is evidenced by successful ‘activation patching’ – the transplantation of representations between proteins – which induces the formation of beta hairpins in a significant 40% of tested cases. This capability indicates that ESMFold doesn’t simply recall previously observed structures, but rather understands and applies causal relationships between amino acid sequences and resulting protein conformations, suggesting a genuine grasp of the biophysical forces at play during the folding process. The model’s ability to accurately predict and even cause folding events through activation patching establishes a new benchmark in computational structural biology.

The study of ESMFold’s inner workings reveals a system not designed, but grown. It isn’t enough to merely observe the model’s predictive power; one must trace the propagation of biochemical information through early layers, the refinement of geometric relationships in the later stages. This echoes a fundamental truth: every refactor begins as a prayer and ends in repentance. As Linus Torvalds once stated, “Talk is cheap. Show me the code.” The researchers haven’t simply talked about interpretability; they’ve dissected the network, revealing how the sequence representation transforms into a functional, folded structure. The architecture wasn’t preordained, but emerged through a process of iterative refinement – a system growing, not built.

What Lies Ahead?

The dissection of ESMFold, and models of its kind, reveals not a solved problem, but a shifting of one. Understanding how a network arrives at a folded structure does not confer control over the inevitable inaccuracies, or predict the nature of its failures. The observed segregation of biochemical and geometric reasoning within the network’s layers is less a design principle, and more a temporary truce in the chaos of gradient descent. Technologies change, dependencies remain.

Future work will undoubtedly probe for greater interpretability – for activations that align neatly with known biophysical constraints. Yet, the temptation to map human understanding onto these systems is a fool’s errand. The network doesn’t ‘understand’ chirality or hydrophobicity; it has merely discovered statistical correlations sufficient to mimic the results. The true challenge lies not in explaining the model, but in accepting its inherent opacity – in treating it as a complex, evolving ecosystem rather than a programmable machine.

Architecture isn’t structure – it’s a compromise frozen in time. The current focus on pairwise representations and activation patching is but one iteration in a relentless cycle of refinement. One suspects that the most significant advances will not come from deeper introspection, but from embracing entirely new inductive biases – from allowing the network to surprise, and from learning to live with the unpredictable consequences.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.06020.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- eFootball 2026 Epic Italian League Guardians (Thuram, Pirlo, Ferri) pack review

- The Elder Scrolls 5: Skyrim Lead Designer Doesn’t Think a Morrowind Remaster Would Hold Up Today

- Demon1 leaves Cloud9, signs with ENVY as Inspire moves to bench

- Bianca Censori finally breaks her silence on Kanye West’s antisemitic remarks, sexual harassment lawsuit and fears he’s controlling her as she details the toll on her mental health during their marriage

- Cardano Founder Ditches Toys for a Punk Rock Comeback

- Outlander’s Caitríona Balfe joins “dark and mysterious” British drama

- The vile sexual slur you DIDN’T see on Bec and Gia have the nastiest feud of the season… ALI DAHER reveals why Nine isn’t showing what really happened at the hens party

- Season 3 in TEKKEN 8: Characters and rebalance revealed

- All The Celebrities In Taylor Swift’s Opalite Music Video: Graham Norton, Domnhall Gleeson, Cillian Murphy, Jodie Turner-Smith and More

- Josh Gad and the ‘Wonder Man’ team on ‘Doorman,’ cautionary tales and his wild cameo

2026-02-07 01:21