Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research reveals that advanced reasoning systems aren’t just processing language, they’re dynamically reshaping their internal representations to grasp the underlying structure of problems.

This work demonstrates representational adaptation in reasoning models, validated through steering interventions that reveal abstract structural understanding independent of surface-level semantics.

Despite recent advances in artificial intelligence, the mechanisms underlying the superior performance of reasoning language models remain largely opaque. This paper, ‘Fluid Representations in Reasoning Models’, investigates how these models process abstract information during complex problem solving. We demonstrate that QwQ-32B dynamically refines its internal representations of problem entities, developing abstract encodings focused on structural relationships rather than surface-level semantics-a process we term Fluid Reasoning Representations. Can understanding and leveraging this dynamic representational adaptation unlock even more powerful and interpretable reasoning capabilities in artificial intelligence?

The Challenge of Robust Reasoning

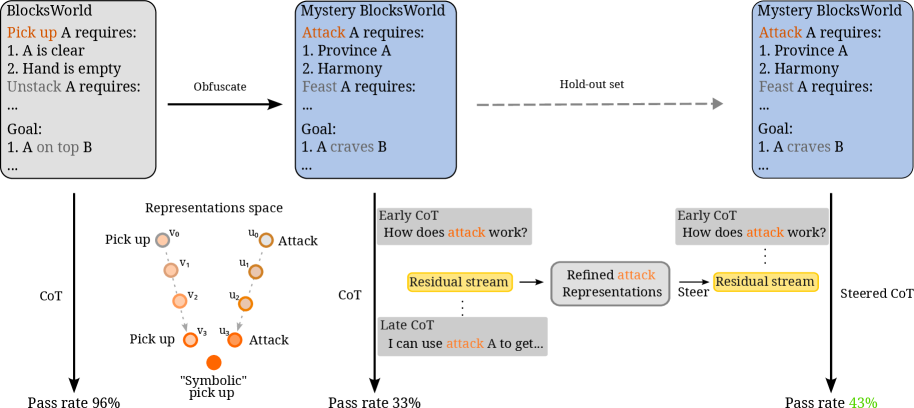

Although contemporary language models demonstrate impressive capabilities in various tasks, genuine robust reasoning continues to pose a significant challenge. Recent evaluations using the Mystery BlocksWorld environment reveal a stark performance disparity; models achieve a mere 33% accuracy in solving complex, multi-step problems within this setting. This contrasts sharply with the 96% accuracy attained on the Standard BlocksWorld, where problem parameters are clearly defined and predictable. This discrepancy underscores a critical limitation: current models struggle when faced with ambiguity, requiring nuanced understanding and flexible problem-solving strategies that extend beyond pattern recognition and rote memorization – capabilities readily demonstrated by human cognition but still elusive for artificial intelligence.

Early artificial intelligence systems excelled at solving clearly defined problems through pre-programmed rules and algorithms, but these approaches proved remarkably inflexible when confronted with real-world ambiguity. Unlike human cognition, which readily adjusts to unforeseen circumstances and incomplete information, classic AI planning often falters when faced with even minor deviations from expected parameters. This rigidity stems from a reliance on precise instructions and a limited capacity to generalize from past experiences; a system designed to stack blocks in a specific configuration might fail entirely if presented with a slightly different starting arrangement. Consequently, these traditionally engineered systems lack the crucial adaptability that characterizes human problem-solving, hindering their ability to navigate the complexities of dynamic environments and novel situations.

The limitations of current language models in complex reasoning tasks underscore a critical need for advancements in how these systems represent knowledge. Unlike humans, who effortlessly construct and revise internal models of the world to navigate challenges, artificial intelligence often relies on pattern recognition without genuine understanding. Developing models capable of building and manipulating these internal representations – akin to mental simulations or abstract thought experiments – is therefore paramount. Such systems would not simply process information, but actively reason with it, adapting strategies and anticipating outcomes in a manner that mirrors the flexibility and robustness of human cognition. This shift from superficial pattern matching to deep representational understanding promises to unlock a new era of artificial intelligence capable of tackling genuinely complex problems.

Architecting Reasoning with QwQ-32B

The QwQ-32B model employs reinforcement learning to develop reasoning skills within simulated environments specifically designed to test problem-solving abilities. Training is conducted on the BlocksWorld and Mystery BlocksWorld domains, which present challenges involving manipulating blocks and inferring hidden properties, respectively. This approach allows the model to learn through trial and error, receiving rewards for correct actions and penalties for incorrect ones, ultimately optimizing its policy for achieving task goals. The use of reinforcement learning enables QwQ-32B to acquire reasoning capabilities without explicit supervision, focusing instead on maximizing cumulative reward within these defined environments.

QwQ-32B distinguishes itself by outputting full, step-by-step reasoning traces alongside its final answers. These traces consist of the model’s internal thought process, detailing the logic and inferences used to arrive at a conclusion. This capability allows researchers to inspect the model’s decision-making at each stage, facilitating analysis of its internal representations and identifying potential biases or flawed reasoning patterns. The extended reasoning traces enable detailed evaluation metrics beyond simple accuracy, such as tracing the origin of specific facts or assessing the consistency of the model’s logic throughout the problem-solving process. This level of transparency is crucial for debugging, improving, and understanding the emergent reasoning abilities of large language models.

QwQ-32B utilizes efficient inference techniques to address the computational demands of large language model-based reasoning agents. Specifically, the model integrates with vLLM, a fast and easy-to-use library for LLM inference and serving. vLLM employs PagedAttention, which optimizes memory usage by managing attention keys and values in pages, reducing redundant memory copies and improving throughput. This optimization is critical for both training, enabling faster iteration and experimentation, and deployment, allowing for real-time responses and scalability in reasoning applications. The implementation with vLLM significantly reduces the latency and resource requirements compared to standard transformer inference methods.

Decoding Representational Dynamics

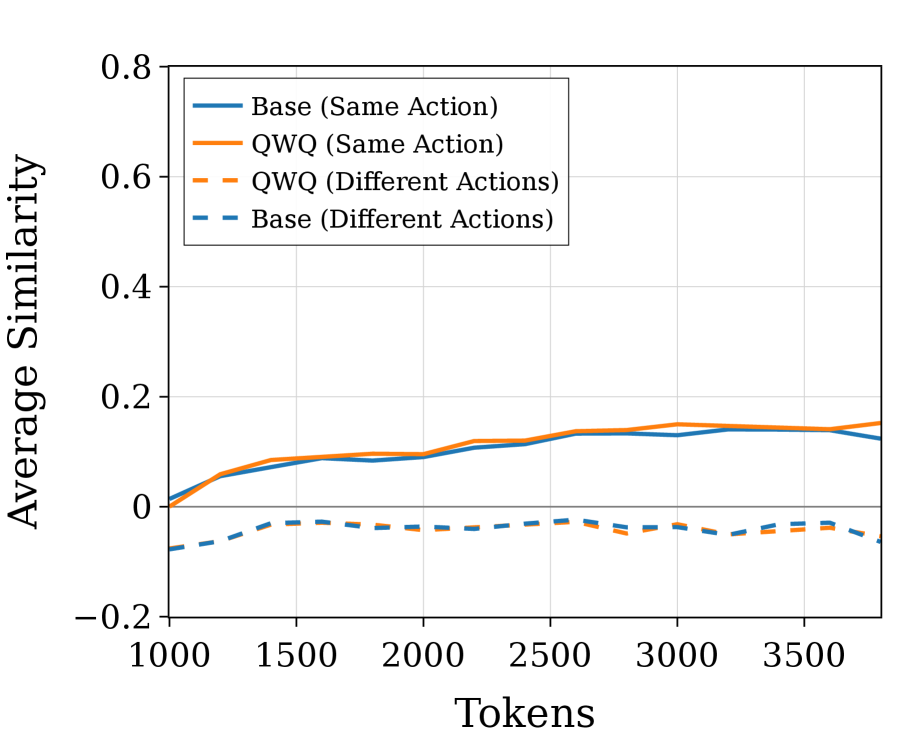

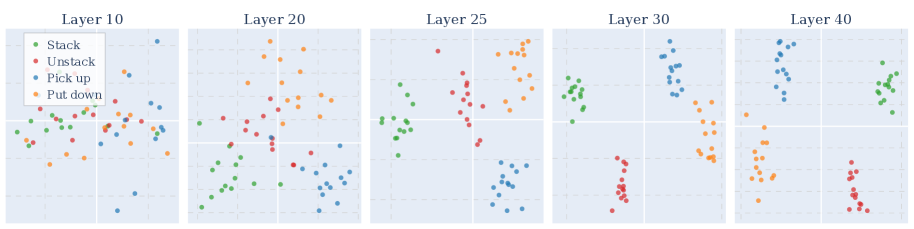

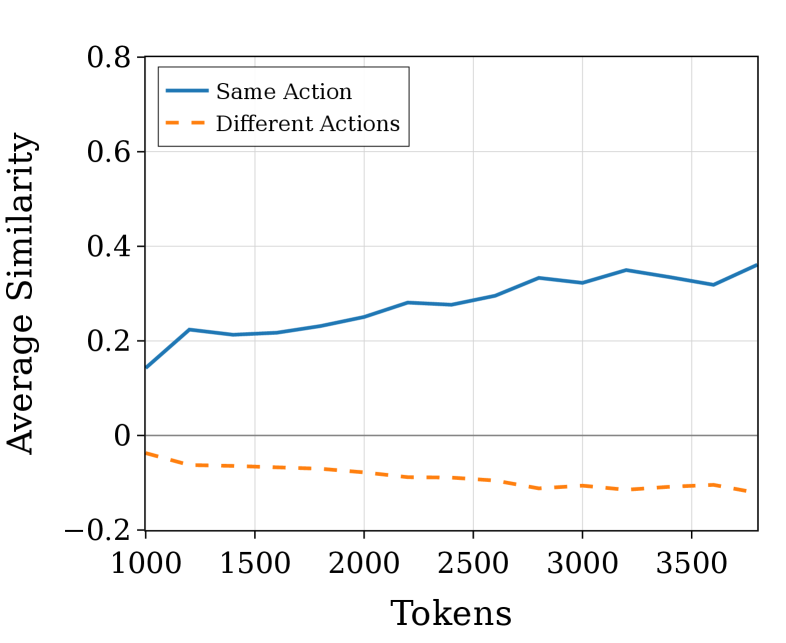

Representational Dynamics characterizes the shifting internal states of a model during problem-solving by analyzing extended reasoning traces – sequences of activations throughout the entire reasoning process. These traces are not static snapshots, but rather demonstrate a continuous evolution of the model’s internal representations as it processes information and progresses toward a solution. This dynamic perspective moves beyond assessing only the final output, allowing researchers to observe how a model arrives at its conclusions by tracking changes in its hidden activations over time. The analysis focuses on identifying patterns and transformations within these representations to understand the model’s cognitive steps and the flow of information during reasoning.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is employed to reduce the dimensionality of the model’s internal state vectors recorded during reasoning, enabling visualization of representational changes over time. By identifying the principal components – those directions in the state space that capture the most variance – researchers can quantify the key features driving the model’s progression towards a solution. These components effectively serve as a lower-dimensional proxy for the full state, allowing for the tracking of how the model’s internal representation evolves with each reasoning step and highlighting the most salient changes in its internal state. The variance explained by each principal component indicates the importance of that feature in the overall dynamic process.

Positive and Negative Steering interventions leverage refined internal representations to enhance model accuracy during reasoning. Positive Steering identifies activations in the model’s internal state that correlate with correct answers and amplifies them in early reasoning steps. Conversely, Negative Steering identifies and suppresses activations associated with incorrect answers. Evaluations demonstrate that applying these techniques-injecting these refined representations into the model at the beginning of the reasoning process-yields accuracy improvements of up to 43% across tested problem sets, indicating the critical role of initial state configuration in achieving successful outcomes.

Towards Symbolic Abstraction in Reasoning

The emergence of fluid reasoning representations within the QwQ-32B model indicates a capacity for generalization that transcends simple pattern matching. Rather than relying on superficial similarities between inputs, the model appears to be constructing internal depictions focused on underlying principles and relationships. This suggests QwQ-32B isn’t merely memorizing solutions but is actively learning to reason about the problems presented, building abstract concepts that can be applied to novel situations. The development of these representations offers a significant step towards artificial general intelligence, demonstrating an ability to move beyond rote learning and engage with problems at a more conceptual level, hinting at an internal ‘understanding’ rather than just statistical correlation.

The emergence of abstract reasoning capabilities in large language models is increasingly supported by the analysis of internal representations. Researchers have demonstrated that averaging the model’s representations of concepts across varied naming schemes-a technique yielding ‘cross-naming representations’-reveals a surprising degree of abstraction. This suggests the model isn’t simply memorizing surface-level associations between names and concepts, but rather constructing a more generalized understanding. By effectively decoupling the way something is labeled from what it is, these cross-naming representations offer compelling evidence that the model is learning to identify underlying principles and relationships, rather than relying solely on specific input patterns. The resultant averaged representations, therefore, appear to capture a deeper, more flexible conceptual understanding, moving beyond simple pattern matching towards true abstraction.

Recent investigations into QwQ-32B’s reasoning capabilities demonstrate that manipulating its internal representations can measurably enhance performance on complex tasks. Specifically, steering experiments-techniques that subtly alter the model’s processing-leveraged cross-naming representations to achieve statistically significant gains in accuracy. At layer 20 of the network, a 1.8% improvement was observed (p=0.044), indicating the changes were unlikely due to random chance. Further refinement at layer 40 yielded a 1.43% increase in accuracy (p=0.021), solidifying the impact of these abstracted representations on the model’s reasoning process. These results suggest that QwQ-32B isn’t simply memorizing patterns, but rather developing a capacity for generalized understanding, where the same concept can be recognized despite variations in presentation.

The study illuminates how reasoning models aren’t simply processing symbols, but actively constructing and refining internal representations – a dynamic process akin to a living organism adapting to its environment. This echoes Bertrand Russell’s observation, “The whole is more than the sum of its parts.” The research demonstrates that these models achieve abstract structural understanding, independent of superficial semantic details, highlighting that the relationships between entities, not the entities themselves, drive effective reasoning. By showcasing representational adaptation through steering interventions, the paper emphasizes that a model’s capacity for robust reasoning stems from this holistic, integrated understanding – a system where modification in one area resonates throughout the entire structure.

Where Do We Go From Here?

The demonstration of dynamically adapting representations within reasoning models offers a compelling, if subtly unsettling, perspective. It suggests these systems are not merely manipulating symbols, but constructing, and revising, internal models of the problems they address. However, the very act of ‘steering’ these representations raises further questions about control, and the potential for unintended consequences. The observed abstraction from surface semantics is elegant, but begs the question: what constraints, if any, govern the formation of these internal worlds? Are they grounded in anything resembling experiential reality, or are they free-floating constructs, exquisitely tuned for pattern matching but devoid of genuine understanding?

Future work must move beyond validating representational adaptation and focus on characterizing the quality of these internal models. Can these representations be reliably probed, audited, and corrected? The current focus on long-form reasoning often overshadows the equally critical need for robustness and error detection. A system capable of elegantly solving a complex problem is less valuable if it consistently fails on simpler, structurally similar tasks. The challenge lies not only in building systems that can reason, but in understanding how they reason, and ensuring that reasoning aligns with desired outcomes.

It is tempting to view these adaptive representations as a step towards artificial general intelligence. But good architecture is invisible until it breaks, and only then is the true cost of decisions visible.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.04843.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- eFootball 2026 Epic Italian League Guardians (Thuram, Pirlo, Ferri) pack review

- The Elder Scrolls 5: Skyrim Lead Designer Doesn’t Think a Morrowind Remaster Would Hold Up Today

- Building Trust in AI: A Blueprint for Safety

- Avengers: Doomsday’s WandaVision & Agatha Connection Revealed – Report

- Cardano Founder Ditches Toys for a Punk Rock Comeback

- How TIME’s Film Critic Chose the 50 Most Underappreciated Movies of the 21st Century

- The vile sexual slur you DIDN’T see on Bec and Gia have the nastiest feud of the season… ALI DAHER reveals why Nine isn’t showing what really happened at the hens party

- Season 3 in TEKKEN 8: Characters and rebalance revealed

- Bob Iger revived Disney, but challenges remain

- Josh Gad and the ‘Wonder Man’ team on ‘Doorman,’ cautionary tales and his wild cameo

2026-02-06 01:30