Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research reveals that while large language models can store information presented within a prompt, they consistently fail to effectively utilize those learned representations for complex reasoning tasks.

![Rapid contextual adaptation within the [latex]OLMo-2-{13}bin[/latex] system-demonstrated on a 16-unit linear topology-suggests a swift collapse of initial states into emergent, contextually-defined representations, indicative of a system prioritizing immediate relevance over sustained historical fidelity.](https://arxiv.org/html/2602.04212v1/x11.png)

Despite their ability to encode in-context information, language models demonstrate limited capacity to deploy learned representations for adaptive reasoning and problem-solving in novel environments.

Despite recent advances in large language models (LLMs), achieving true adaptive intelligence-the ability to generalize to radically new contexts-remains a significant challenge. This is the central question explored in ‘Language Models Struggle to Use Representations Learned In-Context’, which investigates whether LLMs can effectively deploy representations of novel concepts induced from in-context examples. Our work demonstrates that while LLMs can encode contextual information, they struggle to leverage these learned representations for flexible reasoning and problem-solving, even with state-of-the-art reasoning models. This raises a critical question: how can we design language models that not only acquire in-context knowledge, but also reliably deploy it for robust, adaptive behavior?

The Fragile Nature of Understanding: Beyond Pattern Matching

Current language models demonstrate remarkable proficiency in predicting the subsequent word in a sequence, a capability often mistaken for genuine understanding. However, this skill largely relies on statistical correlations within vast datasets, rather than a constructed, internal representation of the world these models describe. While adept at mimicking language patterns, these systems often struggle with tasks requiring common sense reasoning or the ability to infer information not explicitly stated in the training data. This limitation stems from a lack of a cohesive ‘world model’ – a structured understanding of objects, their properties, and the relationships between them – which is crucial for true intelligence and flexible problem-solving. Essentially, these models are powerful pattern-matching engines, but they don’t truly know what they are talking about, hindering their ability to generalize beyond the specific examples encountered during training.

Simply increasing the parameters of a language model, while initially improving performance, ultimately hits a ceiling because it primarily enhances pattern recognition, not genuine comprehension. Current large language models excel at identifying statistical correlations within vast datasets, allowing them to generate plausible text continuations; however, this ability doesn’t equate to understanding the relationships between concepts. True intelligence necessitates the capacity to build an internal representation of how things connect – cause and effect, spatial reasoning, or the properties of objects – enabling models to infer, predict outcomes in novel situations, and generalize beyond memorized data. Therefore, progress requires a shift from simply scaling size to developing architectures that prioritize relational reasoning and abstract understanding, fostering a cognitive ability beyond mere pattern matching.

Current advancements in artificial intelligence are shifting focus from merely predicting the next word in a sequence to constructing internal ‘World Models’ – comprehensive representations of how the world functions. These models aren’t simply about recognizing patterns in data; they strive to build an understanding of underlying causal relationships, allowing for sophisticated inference and prediction beyond the confines of text completion. By learning to simulate environments and anticipate the consequences of actions, these systems gain the ability to plan, reason, and even imagine possibilities not explicitly present in their training data. This represents a critical step towards genuine artificial intelligence, moving beyond statistical mimicry to a form of cognitive understanding where models can not only describe the world but also interact with it – at least, within the simulated landscapes they construct.

In-Context Learning: A Fleeting Adaptation

In-Context Learning (ICL) enables adaptation of large language models (LLMs) to perform tasks without explicit gradient updates or fine-tuning. This is achieved by including a small number of labeled examples, termed the ‘context’, directly within the input prompt. The LLM then utilizes these examples to infer the task objective and generate outputs consistent with the provided demonstrations. The number of examples used can vary, but ICL typically requires significantly fewer labeled instances than traditional supervised learning approaches. This method facilitates rapid task switching and allows LLMs to generalize to new, unseen tasks based solely on the information presented in the prompt, offering a pathway to zero-shot or few-shot learning capabilities.

In-Context Learning (ICL) distinguishes itself from traditional language model adaptation techniques by eliminating the requirement for gradient updates or parameter modification. This is achieved by providing demonstrations – examples of the desired task – directly within the input prompt. Consequently, a single pre-trained model can exhibit diverse behaviors without undergoing retraining for each new task. This approach facilitates rapid deployment of novel functionalities and representations, as the model leverages the provided examples to construct an internal representation of the task, effectively adapting its output without altering its core learned parameters. The absence of parameter updates also enables efficient experimentation and reduces the computational cost associated with frequent model retraining.

Effective evaluation of In-Context Learning (ICL) necessitates the use of tasks specifically designed to assess a language model’s capacity for representation learning and adaptation within a given context. These tasks should move beyond static benchmarks and incorporate dynamic elements that require the model to actively utilize and update its internal representations based on the provided examples. Crucially, evaluation metrics must focus on the model’s performance across a range of contexts and input variations, quantifying its ability to generalize from a limited number of demonstrations without parameter modification. Tasks emphasizing relational reasoning, compositional generalization, and few-shot adaptation are particularly well-suited for probing the representational capabilities unlocked by ICL.

Tracing the Threads: Probing Relational Understanding

The Graph Tracing Task offers a structured method for evaluating the quality of representations learned by language models during in-context learning (ICL). This task involves defining a latent state space represented as a graph, and then prompting the model to predict transitions between states based on provided examples. By controlling the underlying graph structure, researchers can isolate the model’s ability to learn and utilize relational information encoded within the prompt, rather than relying on spurious correlations present in natural language data. Performance is then measured by tracking the model’s accuracy in predicting state transitions as it traverses a random walk over the defined graph, providing a quantitative assessment of its representational capabilities.

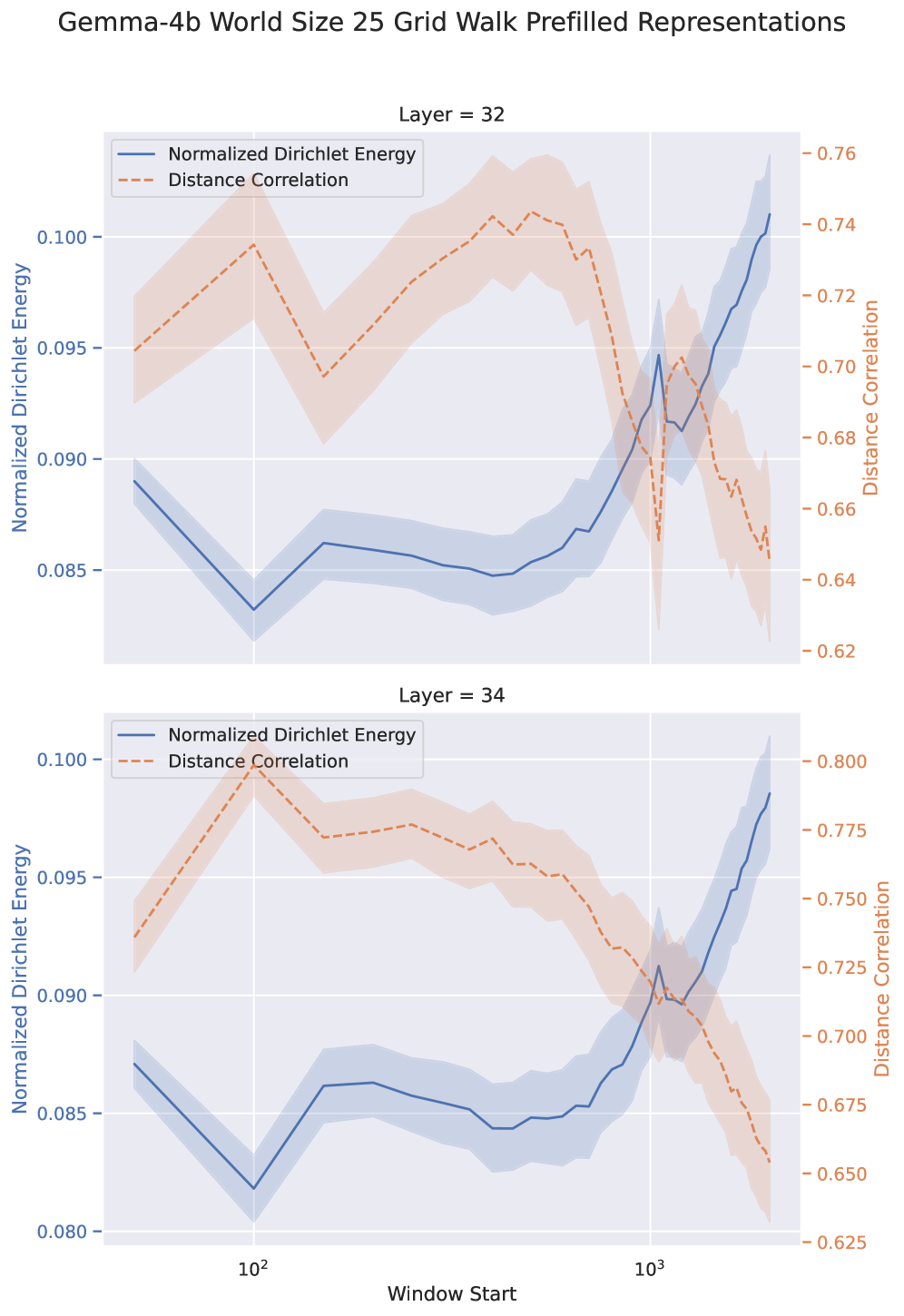

Researchers assess the quality of in-context learning (ICL) representations by simulating random walks within the latent state space encoded by the language model. This methodology involves prompting the model with a sequence of states and evaluating its ability to predict subsequent states based on the established in-context representation. Performance is measured by tracking the model’s accuracy in navigating these simulated walks, with higher accuracy indicating a more meaningful and coherent representation of the underlying state space. The premise is that if ICL successfully creates a functional representation, the model should be able to reliably predict transitions between states during the random walk, demonstrating an understanding of the relationships encoded within the prompt.

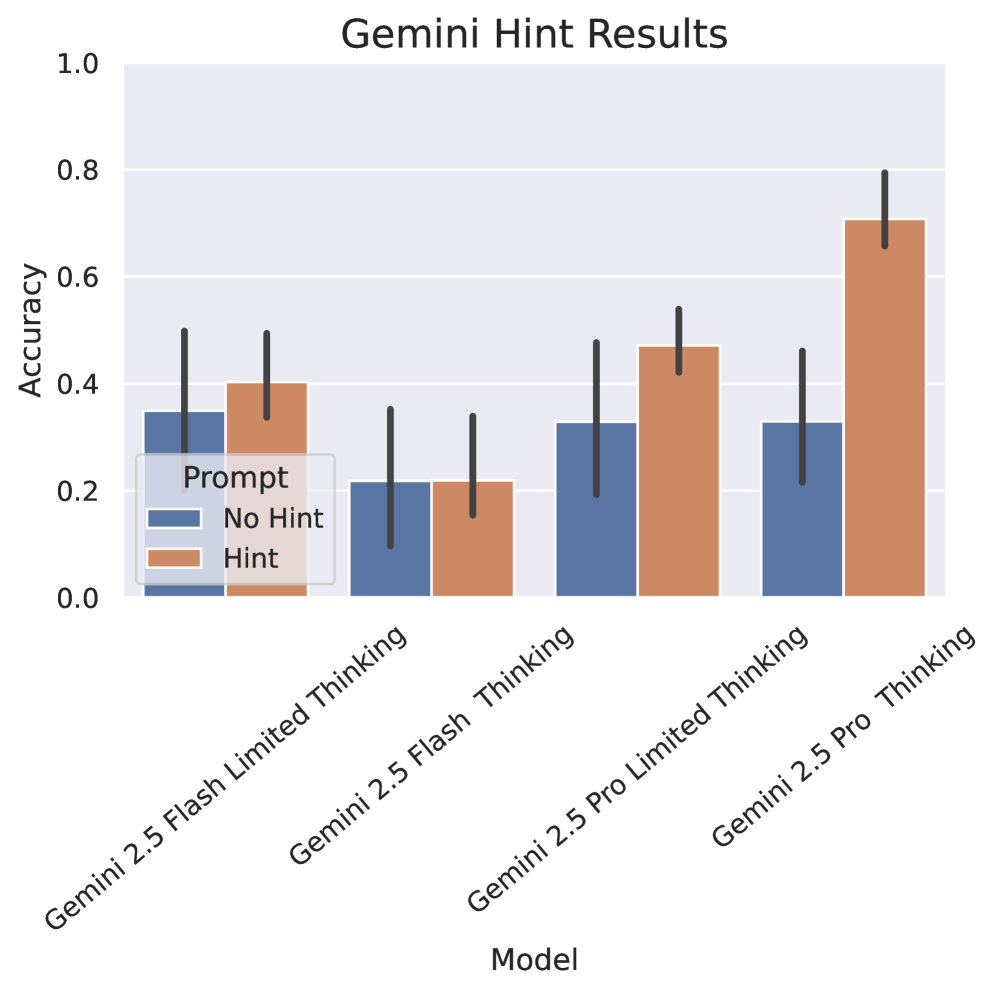

Evaluation of learned representations utilizes distance correlation to quantify the relationship between distances in the model’s representation space and the underlying state space of the task environment; a high correlation indicates fidelity in how the model encodes state transitions. Despite demonstrating an ability to encode topological information – meaning the model captures relationships between states – language models consistently achieve less than 50% accuracy on the Adaptive World Modeling (AWM) task, suggesting that while relational understanding exists, accurate state prediction remains a challenge. This discrepancy indicates that encoding topology is not sufficient for successful world modeling and highlights a gap between representational capacity and functional performance.

The Limits of Context: A Fragile Semantics

A language model’s inherent capability is constrained by its context length-the finite amount of textual information it can consider during any single processing instance. This limitation isn’t merely a technical specification, but a fundamental bottleneck influencing performance; as input sequences exceed this length, the model struggles to maintain coherence and accurately predict subsequent tokens. Effectively, the model’s “attention span” dictates its ability to grasp complex relationships and nuanced meanings within extended texts. While increasing context length is an active area of research, it presents substantial computational challenges, demanding greater memory and processing power. Consequently, strategies for efficiently utilizing existing context windows, or for selectively attending to the most relevant information, are crucial for maximizing a language model’s potential and tackling increasingly sophisticated tasks.

Adaptive World Modeling investigates a language model’s capacity to integrate and utilize entirely new concepts presented within its limited context window. Rather than simply recalling memorized information, this approach assesses how effectively a model can deploy novel semantics-essentially, learn and apply new ‘rules’ on the fly. Researchers probe this adaptability by introducing unfamiliar relationships or definitions within a prompt, then evaluating the model’s ability to correctly apply these newly established concepts to subsequent tasks. This goes beyond mere context length; it examines whether a model can dynamically reshape its internal representation of the world based on the information provided, showcasing a crucial step toward more flexible and intelligent language processing. The success of this process highlights the model’s ability to not just process information, but to genuinely understand and incorporate new knowledge within the scope of a single interaction.

Efforts to bolster In-Context Learning (ICL) through metalearning – teaching models how to learn from examples within a prompt – reveal a surprising limitation in current architectures. While the premise suggests enhanced generalization and adaptability, recent investigations demonstrate a marked decline in performance on Next-Token Prediction tasks when presented with a ‘random walk’ prompt designed to encourage learning. This isn’t merely a failure to learn a specific task; the models exhibit a Dirichlet Energy (DE) Ratio below 1, indicating that the internal representations remain largely unchanged despite the attempt to induce new semantic understanding. Essentially, the model struggles to dynamically adjust its learned features, suggesting that while capable of memorization, the architecture is challenged by truly adaptive learning within the constraints of a single context window.

![Using [latex]gemma-3-{27}b-it[/latex], adaptive world modeling consistently performs well with a fixed long context length.](https://arxiv.org/html/2602.04212v1/x14.png)

The study reveals a curious tendency within these complex systems: an ability to absorb information without necessarily translating it into adaptive behavior. It echoes a principle of graceful decay; the models can encode the new environment, yet struggle with deploying those representations for reasoning. As Henri Poincaré observed, “Mathematics is the art of giving reasons.” The research suggests that while language models excel at the ‘art’ of encoding, the reasoning – the ability to flexibly apply learned representations – remains a significant hurdle. Observing this limitation, the struggle to move beyond pattern recognition to genuine understanding, feels more illuminating than pushing for immediate solutions. The system learns, but its aging process reveals the constraints of its design.

What’s Next?

The current work illuminates a familiar decay within the architecture of intelligence – the distinction between acquisition and application. These language models, demonstrably capable of encoding environmental details within their token representations, falter when tasked with deploying that knowledge. Versioning, in a sense, becomes a form of memory, yet the retrieval process remains brittle. The models amass data, but struggle with the graceful aging necessary for adaptive reasoning. This isn’t a failure of scale, but a fundamental limitation in how representations are grounded and utilized.

Future efforts will likely focus on bridging this gap. The arrow of time always points toward refactoring-toward architectures that prioritize not merely the storage of information, but the dynamic construction of internal ‘world models’ capable of genuine simulation and planning. Simply increasing parameter counts will not resolve the issue; the challenge lies in engineering systems that can meaningfully interpret context, not just statistically correlate tokens.

Ultimately, this research serves as a reminder that intelligence isn’t simply about accumulating knowledge, but about the ability to transcend the limitations of the present. The models can learn about environments, but struggle to truly inhabit them-a distinction that underscores the enduring complexity of building systems capable of flexible, embodied cognition.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.04212.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Robots That React: Teaching Machines to Hear and Act

- Mobile Legends: Bang Bang (MLBB) February 2026 Hilda’s “Guardian Battalion” Starlight Pass Details

- UFL soft launch first impression: The competition eFootball and FC Mobile needed

- eFootball 2026 Epic Italian League Guardians (Thuram, Pirlo, Ferri) pack review

- Olivia Wilde teases new romance with Ellie Goulding’s ex-husband Caspar Jopling at Sundance Film Festival

- 1st Poster Revealed Noah Centineo’s John Rambo Prequel Movie

- Here’s the First Glimpse at the KPop Demon Hunters Toys from Mattel and Hasbro

- The Elder Scrolls 5: Skyrim Lead Designer Doesn’t Think a Morrowind Remaster Would Hold Up Today

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Katie Price’s husband Lee Andrews explains why he filters his pictures after images of what he really looks like baffled fans – as his ex continues to mock his matching proposals

2026-02-05 16:52