Author: Denis Avetisyan

Researchers have developed a model-based control framework to navigate the complexities of high-degree-of-freedom continuum soft robots.

This review details a novel approach to optimal control for rigid-soft underactuated systems, leveraging Cosserat rod theory and implicit strain parameterization for dynamic simulation and model predictive control.

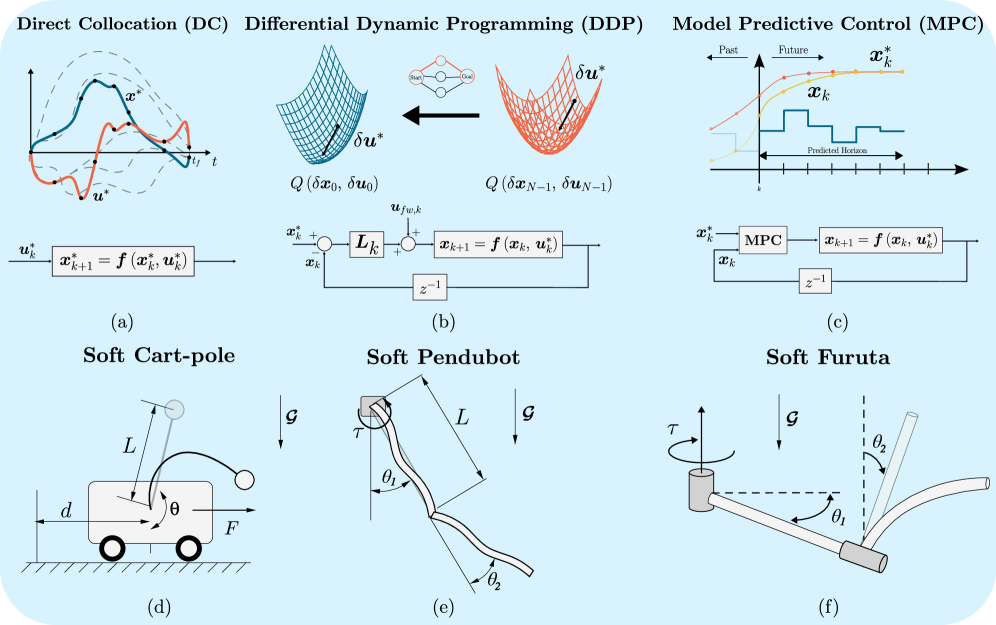

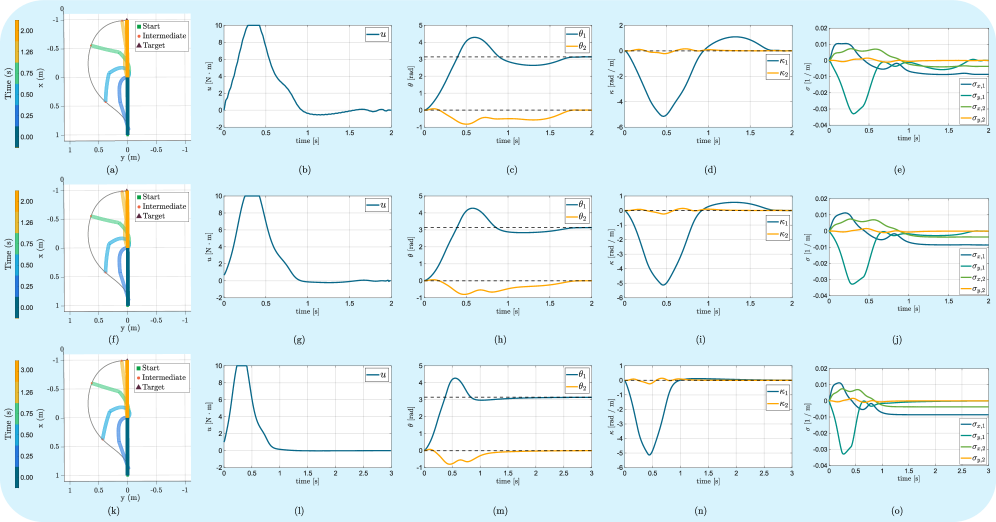

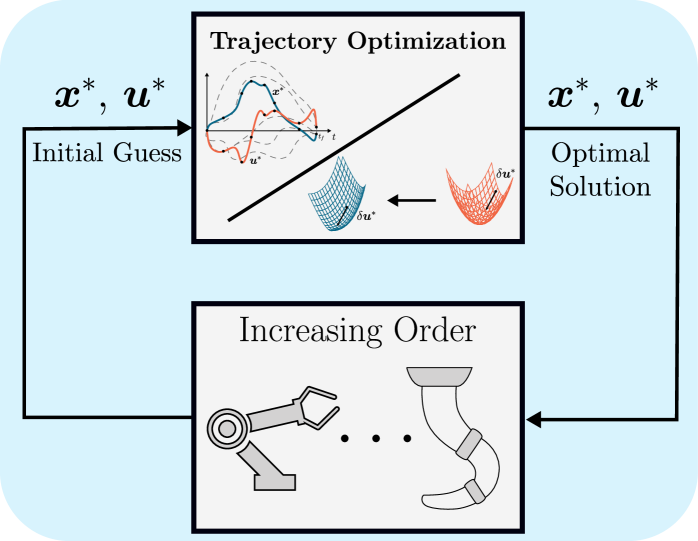

While continuum soft robots offer unique adaptability, their inherent underactuation and complex dynamics pose significant challenges for precise control. This work, ‘Model-based Optimal Control for Rigid-Soft Underactuated Systems’, investigates the application of three optimal control strategies-Direct Collocation, Differential Dynamic Programming, and Nonlinear Model Predictive Control-to dynamic swing-up tasks for hybrid rigid-soft systems. By leveraging the analytical derivatives enabled by a Geometric Variable Strain model and employing implicit integration schemes, the authors demonstrate robust and efficient control of high-degree-of-freedom systems like the Soft Cart-Pole, Pendubot, and Furuta Pendulum. Can these model-based approaches effectively bridge the gap between simulation and real-world deployment for increasingly complex soft robotic applications?

The Inherent Limitations of Rigid Robotics

Conventional robotic systems, built upon the principles of rigid links and joints, often struggle when navigating intricate or unpredictable environments. This limitation stems from their inherent difficulty in adapting to constrained spaces and dynamically changing obstacles. While effective in structured settings like assembly lines, their inflexible nature restricts their application in fields demanding nuanced interaction, such as minimally invasive surgery or search and rescue operations. The rigid design necessitates complex planning algorithms to avoid collisions and maintain stability, increasing computational demands and slowing response times. Consequently, these robots often require substantial workspace clearance and precise environmental mapping – prerequisites that are frequently absent in real-world scenarios. This reliance on predefined paths and static environments underscores the need for robotic designs capable of intrinsic adaptability and seamless interaction with complex surroundings.

Continuum robots distinguish themselves through designs prioritizing flexibility, enabling navigation within intricate and confined spaces inaccessible to their rigid-bodied counterparts. Unlike traditional robots that rely on discrete joints, these robots utilize flexible materials – such as polymers, or braided structures – to achieve locomotion. This inherent compliance drastically improves safety when interacting with unpredictable environments or humans, as collisions are less likely to result in damage or injury. The adaptability extends to surgical procedures, minimally invasive exploration, and search-and-rescue operations, where the ability to bend, twist, and conform to complex geometries is paramount. Consequently, continuum robots are increasingly favored in applications demanding dexterity, safety, and the capacity to operate within highly constrained spaces.

Despite the advantages of continuum robots in navigating complex spaces, their inherent deformability introduces substantial modeling and control challenges. Unlike rigid-bodied robots where motion can be predicted using well-established kinematic and dynamic equations, continuum robots require representations that account for infinite degrees of freedom and complex material behavior. Accurately capturing the robot’s pose – its shape and position in space – demands sophisticated mathematical frameworks, often relying on discretized models or assumptions about material properties. Furthermore, controlling these robots necessitates inverse kinematic and dynamic solutions that are computationally intensive and sensitive to modeling errors. Even slight inaccuracies in representing the robot’s geometry or its response to applied forces can lead to significant deviations from the desired trajectory, hindering performance and potentially compromising safety in delicate operations.

Achieving nuanced control of continuum robots fundamentally depends on developing accurate computational models that capture their intricate geometry and material properties. Unlike rigid robots where motion is predictable based on joint angles, continuum robots deform continuously, requiring representations that account for bending, twisting, and stretching along their entire length. Researchers employ techniques like Cosserat rod theory and finite element analysis to describe these deformations, often incorporating material models that capture non-linear strain behavior and hysteresis. These models aren’t merely descriptive; they form the basis of control algorithms that predict the robot’s response to applied forces and, crucially, allow for inverse kinematic solutions – determining the necessary actuation to achieve a desired shape or position. The fidelity of these representations directly impacts the robot’s ability to navigate complex environments, manipulate delicate objects, and perform tasks with the required precision and repeatability.

Geometric Variable Strain: A Rigorous Framework for Continuum Kinematics

Geometrically Variable Strain (GVS) establishes a kinematic framework for representing the three-dimensional deformation of continuum robots. Unlike discrete robot models reliant on joint angles, GVS describes robot configurations using continuous geometric parameters, allowing for the modeling of arbitrary shapes achievable by the robot. This is accomplished by dividing the robot into a series of segments, each characterized by its own local strain – a measure of deformation. By varying the strain applied to each segment, and defining appropriate kinematic constraints, GVS can theoretically represent any reachable configuration of the continuum robot, providing a complete description of its deformation space. The method’s versatility stems from its ability to accommodate varying levels of complexity in segment geometry and strain application, from simple constant curvature to complex, spatially varying deformations.

Representations of continuum robot deformation using constant, linear, or affine segments offer a trade-off between computational complexity and modeling accuracy. Constant curvature models, while simplest to compute, provide the lowest fidelity representation of complex bending. Linear segments, effectively approximating the robot as a series of hinged links, improve accuracy by allowing for changes in curvature but still lack the smoothness of true continuum behavior. Affine segments, representing deformation with [latex] \mathbb{R}^n [/latex] transformations, provide the highest fidelity by capturing both translation and rotation, and allowing for non-constant curvature, but at a significantly increased computational cost compared to constant or linear segment models.

Curvature, defined as the rate of change of tangent angle along a curve, is a critical parameter in continuum robot behavior because it directly impacts the robot’s bending stiffness and reachable workspace. Constant curvature segments simplify modeling but limit the precision with which complex shapes can be achieved. Variable curvature allows for more nuanced control of deformation, enabling the robot to navigate constrained spaces and achieve a wider range of poses. The distribution of curvature along the robot’s length determines its overall bending profile and influences its ability to exert force and resist external loads. Specifically, regions of high curvature concentrate stress, while gentler curves distribute it more evenly. [latex] \kappa = \frac{d\theta}{ds} [/latex] mathematically defines curvature, where θ is the tangent angle and [latex] s [/latex] is the arc length.

Characterizing a continuum robot’s deformation space-that is, the full range of possible shapes it can achieve-is crucial for accurate modeling and control. Geometrically variable strain approaches facilitate this characterization by defining deformation through quantifiable geometric properties like curvature and segment lengths. Unlike simplified models relying on fixed assumptions, these methods allow representation of complex, non-linear deformations by varying these parameters. This leads to a more complete description of the robot’s configuration space, enabling precise prediction of its behavior and improved control algorithms, as the robot’s reachable configurations are explicitly defined by the range of geometric variables.

Optimized Control: Achieving Precision Through Advanced Algorithms

Optimal control problem formulation defines the process of determining the ideal trajectory for a continuum robot by mathematically specifying a cost function to be minimized, subject to constraints representing the robot’s dynamics and operational limits. This formulation typically involves defining a state vector [latex]x[/latex] representing the robot’s configuration, a control input vector [latex]u[/latex] influencing its motion, and a cost function [latex]J[/latex] quantifying the desired performance – such as minimizing energy consumption or maximizing tracking accuracy. The robot’s dynamics are expressed as a set of differential equations describing the evolution of the state vector over time, and constraints are imposed to ensure the trajectory remains within feasible limits – preventing collisions, respecting joint limits, or satisfying other operational requirements. The resulting optimization problem aims to find the control input [latex]u(t)[/latex] that minimizes [latex]J[/latex] while satisfying the dynamic equations and constraints.

While Linear Quadratic Regulator (LQR) and Trajectory Optimization represent established methodologies for continuum robot control, their implementation frequently demands substantial computational resources. LQR, although providing an analytical solution for linear systems with quadratic cost functions, requires the calculation of the Riccati equation and can become intractable for highly nonlinear robot dynamics. Trajectory Optimization, which formulates the control problem as a nonlinear program, involves iteratively solving a series of optimization problems to determine optimal control inputs. The complexity of these calculations scales with the dimensionality of the robot’s state and input spaces, and the length of the trajectory being optimized; therefore, practical application often necessitates approximations or simplifications that may compromise solution optimality. Furthermore, ensuring convergence of iterative solvers within acceptable timeframes remains a significant challenge.

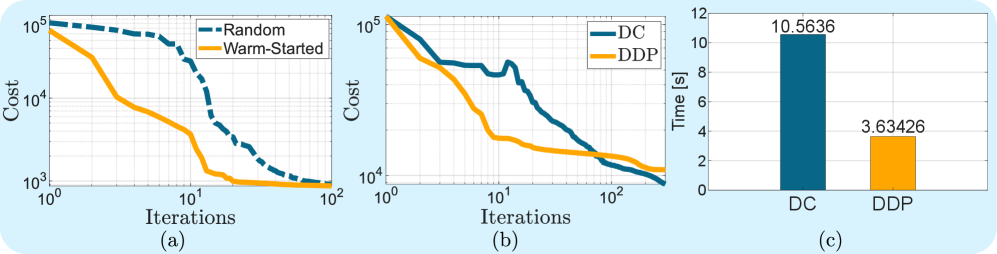

Direct Collocation and Differential Dynamic Programming (DDP) are both numerical methods employed to solve optimal control problems arising in continuum robotics. Direct Collocation discretizes the robot’s continuous dynamics and cost function into a finite-dimensional nonlinear program, solvable by standard optimization solvers. This approach transforms the trajectory optimization into a constrained optimization problem with trajectory points as decision variables. DDP, conversely, is a sequential quadratic programming method that iteratively refines an initial guess trajectory by linearizing the dynamics and cost function around the current estimate. It utilizes the inverse of the Hessian of the second-order necessary conditions to compute efficient search directions. While Direct Collocation can be more robust to initial guesses, DDP typically exhibits faster convergence rates when provided with a reasonably good initial trajectory, due to its exploitation of local curvature information.

Box-Differential Dynamic Programming (Box-DDP) and Implicit DDP represent algorithmic improvements over Direct Collocation for solving optimal control problems in continuum robotics. Benchmarking on the Soft Cart-Pole system demonstrates these advanced methods achieve a 2.9x reduction in computational time per iteration. This performance gain is attributed to enhancements in stability and efficiency during the iterative optimization process, allowing for faster convergence to optimal trajectories. These techniques are particularly valuable for real-time control applications and complex robotic systems where computational resources are limited.

Simulation and Implementation: Validating Theory Through Practical Application

SoRoSim functions as a robust environment for the detailed simulation of continuum robots, enabling researchers to test and refine control strategies before physical implementation. This platform moves beyond simplified models by incorporating realistic physical properties and dynamic behaviors, crucial for predicting performance in complex scenarios. Through SoRoSim, developers can iterate on designs and algorithms virtually, significantly reducing development time and cost. The platform’s capabilities extend to validating the efficacy of novel control approaches, such as those designed for precise manipulation or navigating constrained spaces, ultimately accelerating the translation of research into practical applications like minimally invasive surgical tools and adaptable manufacturing systems.

The dynamic simulations within SoRoSim, a powerful platform for continuum robot modeling, are fundamentally built upon the Recursive Newton-Euler Algorithm (RNEA). This computationally efficient method allows for the swift and accurate calculation of forces and torques acting on each segment of the robot, even with complex, multi-degree-of-freedom configurations. Unlike traditional Newton-Euler methods that propagate forces forward, RNEA recursively calculates forces and torques starting from the end-effector, working backwards towards the base. This approach minimizes numerical error and computational cost, enabling real-time simulation of intricate robotic movements. The algorithm accounts for inertia, Coriolis and centrifugal forces, gravity, and external loads, providing a robust foundation for validating control strategies and optimizing robot performance in diverse applications. [latex] \tau = J^T F + \dot{J}^T \dot{F} + g [/latex] represents a simplified view of the forces calculated through RNEA, where τ is the joint torque, [latex] J [/latex] is the Jacobian matrix, [latex] F [/latex] is the force vector, and [latex] g [/latex] represents gravity.

The efficacy of continuum robot control hinges on swiftly achieving stable, accurate movements, and recent research demonstrates how combining precise modeling, sophisticated optimization techniques, and realistic simulation environments accelerates this process. Specifically, studies utilizing the SoRoSim platform have shown that employing a ‘warm-start’ strategy – leveraging prior simulation data to initialize optimization algorithms – dramatically reduces convergence times. This was notably observed with the Soft Furuta Pendulum, a complex dynamic system where the warm-start approach facilitated significantly faster attainment of optimal control parameters. This ability to rapidly refine control strategies not only streamlines the development process but also paves the way for real-time control applications in fields demanding precise and responsive robotic systems, such as minimally invasive surgical procedures and intricate manufacturing tasks.

The convergence of accurate continuum robot simulation and robust control strategies promises transformative advancements across multiple critical fields. In minimally invasive surgery, these robots offer the dexterity and precision to navigate complex anatomical structures with reduced trauma. For search and rescue operations, their adaptability allows access to unstable or confined environments, potentially locating survivors where conventional robots cannot reach. Furthermore, in advanced manufacturing, continuum robots facilitate intricate assembly tasks and inspection processes, enhancing precision and efficiency in production lines. This synergy isn’t simply about automation; it’s about creating robotic systems capable of performing delicate and demanding tasks in environments previously inaccessible, paving the way for safer, more effective, and ultimately, more impactful robotic interventions.

Future Directions: Expanding the Horizon of Continuum Robotics

Model Predictive Control (MPC) presents a compelling strategy for enhancing the adaptability and resilience of continuum robots operating in unpredictable environments. Unlike traditional control methods, MPC doesn’t simply react to disturbances; it proactively anticipates future system behavior by repeatedly solving an optimization problem over a finite time horizon. This allows the robot to calculate a sequence of control actions that minimize a defined cost function – such as minimizing energy consumption or maximizing tracking accuracy – while simultaneously respecting physical constraints like joint limits or collision avoidance. Crucially, MPC can incorporate real-time sensor data and adjust the control strategy on the fly, enabling robust performance even in the face of modeling uncertainties or external disturbances. The computational demands of solving these optimization problems are being addressed through advancements in algorithms and hardware, making MPC increasingly viable for the rapid, precise, and reliable control required by increasingly sophisticated continuum robotic systems.

Accurately predicting how continuum robots bend and stretch remains a significant challenge, as their deformations are inherently complex and nonlinear. Current modeling techniques often rely on simplified assumptions that limit their ability to capture the full range of possible shapes. Ongoing research focuses on developing geometrically variable strain representations – mathematical frameworks that can more faithfully describe these intricate deformations, accounting for variations in curvature, torsion, and material properties along the robot’s body. These advanced representations move beyond traditional beam or finite element models by incorporating more sophisticated geometric descriptions and allowing for localized strain variations. This detailed modeling capability is crucial for precise control, robust path planning, and ultimately, enabling continuum robots to navigate constrained environments and perform delicate manipulations with greater dexterity and reliability.

The future capabilities of continuum robots are inextricably linked to advancements in sensing technologies. Current limitations in accurately perceiving the robot’s pose and interaction forces necessitate the incorporation of modalities beyond traditional encoders and force sensors. Researchers are exploring the integration of flexible sensors directly onto the robot’s body – akin to artificial skin – to provide continuous, distributed measurements of bending, strain, and contact. Furthermore, vision-based systems, including stereo cameras and event-based sensors, offer the potential for real-time 3D reconstruction of the robot’s shape and surrounding environment. Combining these sensory inputs with sophisticated data fusion algorithms will allow continuum robots to not only ‘know’ their configuration with greater precision, but also to adapt their behavior in response to unpredictable external forces and complex terrains, ultimately enabling more robust and intelligent operation in unstructured environments.

The future of continuum robotics hinges on a synergistic interplay between several key innovations. As model predictive control algorithms become more refined, these robots will gain the capacity to dynamically adapt to unforeseen circumstances and maintain stable performance in complex environments. Simultaneously, increasingly accurate geometric modeling – capable of representing the intricate strains inherent in flexible structures – will allow for precise control and predictable movement. However, it is the integration of these computational advancements with sophisticated sensing technologies – providing real-time environmental feedback – that will truly unlock the potential for intelligent behavior. This convergence promises a new generation of continuum robots capable of navigating challenging terrains, performing delicate manipulations, and ultimately, operating with a level of autonomy and versatility previously unattainable, impacting fields from minimally invasive surgery to search and rescue operations.

The pursuit of controlling underactuated systems, as demonstrated in this work concerning continuum soft robotics, demands a level of precision mirroring mathematical rigor. The framework presented-leveraging Cosserat rod theory and model-based optimal control-highlights the necessity of a provable, rather than merely empirically validated, approach. This aligns perfectly with Carl Friedrich Gauss’s assertion: “I have had no time to make it elegant.” Elegance, in this context, isn’t superficial aesthetics, but the inherent correctness and demonstrable validity of the underlying mathematical model-a proof of correctness always outweighs intuition when dealing with the complexities of dynamic simulation and control for high-degree-of-freedom systems.

What’s Next?

The presented framework, while demonstrating efficacy in simulated environments, merely scratches the surface of the challenges inherent in controlling underactuated, continuum systems. The reliance on Cosserat rod theory, though mathematically elegant, introduces limitations when confronted with extreme deformations or complex material properties. Future work must address the inevitable discrepancies between modeled elasticity and physical reality – a divergence that grows exponentially with system complexity. The current approach, focused on implicit strain parameterization, necessitates careful consideration of numerical stability, especially during long-horizon predictions.

A critical next step lies in the rigorous validation of these algorithms on physical hardware. Simulations, however sophisticated, remain abstractions. The chaotic interplay of sensor noise, actuator hysteresis, and unmodeled dynamics will undoubtedly expose the brittleness of purely model-based approaches. Furthermore, the computational cost associated with model predictive control demands exploration of more efficient solvers and reduced-order modeling techniques.

Ultimately, the pursuit of graceful, reliable control for these systems requires a shift in perspective. The focus should move beyond simply achieving a desired trajectory and toward developing algorithms capable of learning from their errors – embracing the inherent uncertainty of the physical world. In the chaos of data, only mathematical discipline endures, but even the most elegant theory must yield to the evidence of experiment.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.03435.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Heartopia Book Writing Guide: How to write and publish books

- Robots That React: Teaching Machines to Hear and Act

- Mobile Legends: Bang Bang (MLBB) February 2026 Hilda’s “Guardian Battalion” Starlight Pass Details

- UFL soft launch first impression: The competition eFootball and FC Mobile needed

- Olivia Wilde teases new romance with Ellie Goulding’s ex-husband Caspar Jopling at Sundance Film Festival

- The Elder Scrolls 5: Skyrim Lead Designer Doesn’t Think a Morrowind Remaster Would Hold Up Today

- eFootball 2026 Epic Italian League Guardians (Thuram, Pirlo, Ferri) pack review

- Gold Rate Forecast

- 1st Poster Revealed Noah Centineo’s John Rambo Prequel Movie

- Here’s the First Glimpse at the KPop Demon Hunters Toys from Mattel and Hasbro

2026-02-04 10:49