Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new control architecture seamlessly integrates macro and micro manipulation, offering improved force control and performance in complex assembly tasks.

This review details a unified control system leveraging an active remote center of compliance for enhanced macro-micro manipulation in industrial applications.

While traditional macro-micro manipulation systems limit interaction control bandwidth by assigning position control solely to the macro manipulator, this paper-‘A Unified Control Architecture for Macro-Micro Manipulation using a Active Remote Center of Compliance for Manufacturing Applications’-introduces a novel control architecture that actively incorporates the macro manipulator into the interaction control loop. This unified approach achieves a [latex]2.1\times[/latex] increase in control bandwidth compared to state-of-the-art leader-follower architectures and a [latex]12.5\times[/latex] improvement over traditional robot-based force control. By leveraging surrogate models for efficient controller design and adaptation, this work demonstrates improved performance in tasks such as collision handling, force trajectory following, and industrial assembly; but how might this architecture be further optimized for dynamic and unpredictable manufacturing environments?

The Inevitable Challenge of Precision

Conventional industrial robots, while adept at repetitive macro-movements, frequently encounter difficulties when tasked with intricate assembly procedures requiring both meticulous positioning and controlled force application. This limitation arises from the inherent challenges in simultaneously managing a robot’s spatial location and the interaction forces it exerts on components. Unlike the open-loop control sufficient for simple pick-and-place operations, precise assembly demands a closed-loop system capable of sensing contact, adapting to variations in component tolerances, and applying just the right amount of pressure – a capability often exceeding the design parameters of standard robotic arms. Consequently, delicate parts are susceptible to damage, assemblies may fail to meet specifications, and the automation of complex manufacturing processes remains a significant hurdle.

The inherent difficulty in precision assembly arises from the complex interplay between a robot’s movements and the forces it exerts on components during contact. Traditional robotic systems often treat motion and force control as separate entities, creating a mismatch when assembling delicate or tightly-fitting parts. This decoupling can result in excessive force being applied, leading to component damage-such as cracking or deformation-or, conversely, insufficient force causing assembly failure. The problem isn’t a lack of robotic strength or speed, but rather the inability to seamlessly coordinate these attributes with the nuanced demands of each assembly step, particularly when dealing with variations in part tolerances or unexpected contact scenarios. Consequently, achieving reliable, damage-free assembly requires sophisticated control algorithms capable of dynamically adjusting both motion and force in real-time, a significant hurdle in automating complex manufacturing processes.

The ability to reliably automate complex manufacturing hinges on overcoming current limitations in precision assembly. Successfully tackling these challenges isn’t merely about increased efficiency; it directly impacts product quality and consistency. Industries requiring intricate component integration – such as electronics, medical devices, and aerospace – stand to benefit most from robust, automated assembly systems. Improved precision minimizes defects, reduces waste, and allows for the creation of increasingly sophisticated products with tighter tolerances. Consequently, investment in technologies that enhance force control and positional accuracy during assembly is not simply a technological advancement, but a critical driver of economic growth and innovation across numerous sectors.

Synergistic Manipulation: Bridging Scales

Macro-micro manipulation utilizes a hierarchical robotic system comprised of a large-workspace robot and a high-precision micro-manipulator to achieve enhanced dexterity and force control. The large-workspace robot provides broad range of motion and positions the micro-manipulator to the general vicinity of a target. Subsequently, the micro-manipulator executes precise movements and applies controlled forces for delicate operations. This configuration effectively combines the speed and reach of a macro-scale robot with the accuracy and sensitivity of a micro-scale robot, enabling complex tasks requiring both coarse and fine manipulation capabilities.

The macro-micro manipulation architecture utilizes a two-stage positioning process. Initially, a large-workspace robot – the macro robot – rapidly moves the end-effector to the general vicinity of the target location. Subsequently, a high-precision micro-manipulator refines this positioning with sub-millimeter accuracy. This division of labor extends to force control; while the macro robot provides overall positioning and gross force application, the micro robot executes delicate force-sensitive tasks, such as applying precise insertion forces or maintaining contact during assembly. This sequential approach optimizes both speed and accuracy, enabling operations beyond the capabilities of either robot operating independently.

The synergy between macro and micro manipulation systems facilitates complex operations requiring both broad workspace access and high precision. The macro robot provides rapid, large-scale positioning to bring components into the general vicinity of a target, while the micro-manipulator executes the final, delicate stages of assembly or interaction. This division of labor is particularly beneficial for tasks such as inserting fragile components, aligning parts within tight tolerances, and applying controlled forces during contact, as the micro robot’s precision minimizes the risk of damage or misalignment that could occur with a single, larger system attempting the entire operation.

![The macro-micro manipulator is modeled as a system comprising a macro manipulator ([latex]Index_{MM}[/latex]) and a micro manipulator ([latex]Index_{\mu}[/latex]) with active ([latex]Index_{a}[/latex]) and passive ([latex]Index_{p}[/latex]) components, each represented by corresponding transfer functions.](https://arxiv.org/html/2602.01948v1/x2.png)

Modelling for Resilience: A System’s Foundation

Accurate system identification is foundational for developing reliable control models in macro-micro systems due to the inherent complexities arising from the interaction of scales and dynamics. These systems, comprised of both macroscopic and microscopic manipulators, require precise modelling of each component and their coupled behavior. Errors in identifying system dynamics-including mass, inertia, friction, and actuator characteristics-directly propagate into control model inaccuracies, leading to degraded performance, instability, and reduced precision. Consequently, robust identification techniques, utilizing data-driven methods and potentially incorporating physics-based models, are crucial for obtaining accurate parameter estimates and ensuring the effectiveness of any subsequent control strategy. This is particularly important given the potential for significant variations in dynamics between the macro and micro scales.

Surrogate models are utilized to reduce the computational complexity associated with controlling macro-micro systems by approximating the identified dynamic behavior with a simplified representation. These models, derived from system identification techniques, enable the design of controllers that would be impractical or impossible to implement directly on the full, high-fidelity system due to real-time processing constraints. By leveraging a reduced-order or computationally efficient surrogate, controller design and implementation become feasible, facilitating rapid prototyping and deployment. This approach allows for complex control algorithms to be executed with the necessary speed and precision for effective macro-micro system operation, bypassing the limitations imposed by the original system’s dynamics.

Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed control architecture achieves a force control bandwidth of 17.34 Hz. This represents a 2.1x improvement over the performance of a state-of-the-art leader-follower control approach, which yielded a bandwidth of 8.13 Hz. Furthermore, the proposed architecture exhibits a 12.5x increase in force control bandwidth compared to a traditional Rigidity-Based (RB) approach, which achieved a bandwidth of only 1.39 Hz. These figures indicate a substantial enhancement in the system’s ability to respond to and regulate applied forces.

H-infinity control provides a mathematically rigorous approach to designing controllers for macro-micro systems that are resilient to model uncertainties and external disturbances. This method formulates the control problem as minimizing the [latex]H_{\in fty}[/latex] norm of a closed-loop transfer function, effectively bounding the influence of disturbances and modelling errors on the system’s output. By explicitly accounting for these factors during controller synthesis, H-infinity control guarantees closed-loop stability and ensures a specified level of performance, even in the presence of significant uncertainties in the system dynamics or unforeseen external disturbances acting on the macro and micro manipulators. This contrasts with methods that assume perfect knowledge of the system, which can lead to instability or degraded performance when faced with real-world conditions.

Leader-follower (LF) control establishes a hierarchical relationship between a macro manipulator and a micro manipulator to achieve coordinated motion. The macro manipulator defines the overall trajectory, serving as the ‘leader’, while the micro manipulator, functioning as the ‘follower’, precisely tracks the leader’s movements with adjustments for scale and kinematic differences. This approach simplifies the control problem by decoupling trajectory planning from precise tracking, allowing the micro manipulator to focus on maintaining synchronization and achieving high-precision movements relative to the macro manipulator’s path. Successful implementation relies on accurate communication of position and velocity data between the two systems, and compensation for any inherent delays or disturbances to maintain stability and ensure synchronized operation.

![This [latex]\mathcal{H}_\in fty[/latex] synthesis model, denoted as [latex]T(s)[/latex], relates reference signals ([latex]rr[/latex]), model outputs ([latex]yy[/latex]), exogenous inputs like disturbances ([latex]ww[/latex]), and performance functions ([latex]zz[/latex]) within a generalized state space framework.](https://arxiv.org/html/2602.01948v1/x10.png)

Beyond Automation: Towards Adaptable Assembly

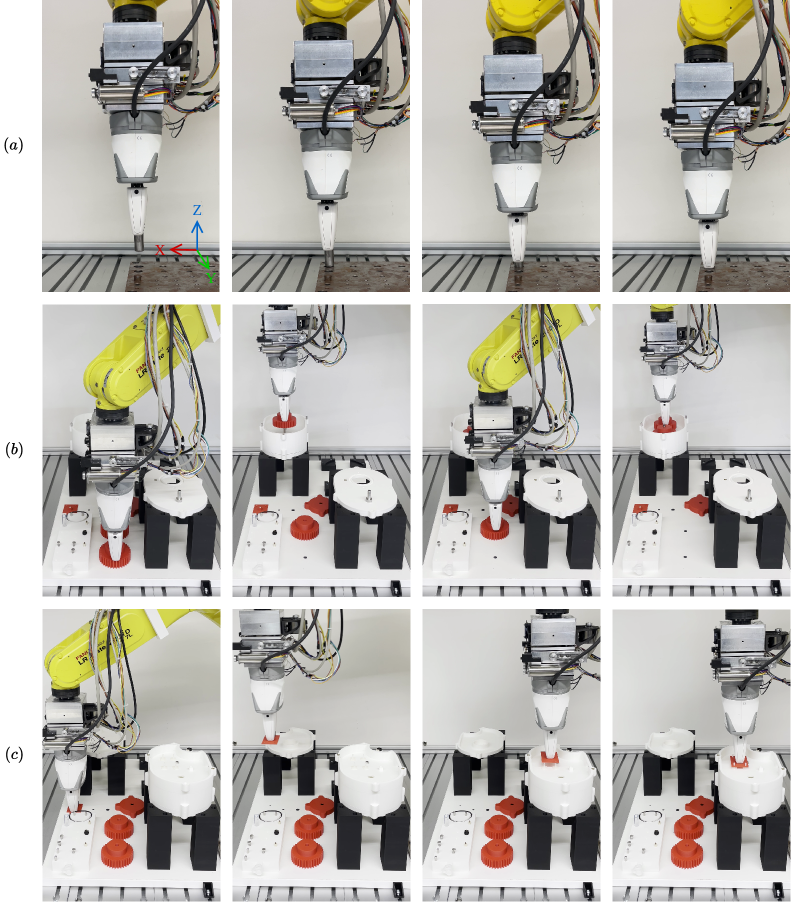

The adaptability of macro-micro manipulation is clearly demonstrated through its successful application to diverse assembly tasks. Researchers have effectively utilized this approach to automate the precise and often delicate processes of peg-in-hole assembly, gear assembly, and even circuit board construction. This versatility stems from the system’s ability to combine large-scale movements for initial positioning with fine-tuned, microscopic adjustments for accurate component placement. The technique proves particularly beneficial in scenarios demanding high precision and intricate manipulation, opening pathways for automation in industries previously reliant on manual labor and specialized skillsets. This broad applicability suggests macro-micro manipulation isn’t limited to specific applications, but rather offers a foundational advancement in automated assembly technologies.

Automation of intricate assembly tasks, previously requiring significant human dexterity, is now demonstrably achievable through this macro-micro manipulation approach. By precisely coordinating large-scale movements with fine-tuned adjustments, the system successfully navigates the challenges inherent in delicate procedures like component insertion and alignment. This capability not only accelerates production cycles – evidenced by substantial time reductions in tasks such as peg-in-hole assembly, gear construction, and circuit board fabrication – but also minimizes the potential for human error, leading to higher quality products and reduced waste. The resulting gains in both speed and precision position this technology as a transformative asset for modern manufacturing, enabling the efficient creation of increasingly complex and sophisticated devices.

Demonstrated across multiple assembly tasks, the proposed macro-micro manipulation method exhibits substantial gains in efficiency. Specifically, peg-in-hole insertion is completed in just 6.56 seconds, a marked improvement over the 19.35 seconds required by the leading force-based approach (LF) and the 29.77 seconds of the robotic baseline (RB). This speed advantage extends to more complex assemblies; the complete gear assembly takes 63.50 seconds, significantly less than the 85.10 seconds of LF and 138.50 seconds of RB. Even in the precision-demanding task of circuit board assembly, the method achieves a time of 26.70 seconds, outperforming both LF (27.90 s) and RB (40.00 s). These results collectively indicate a substantial acceleration of assembly processes, suggesting potential for widespread application in manufacturing environments.

Ongoing development centers on equipping the macro-micro manipulation system with sophisticated sensor feedback mechanisms and adaptive control strategies. This integration aims to move beyond pre-programmed routines, allowing the system to respond dynamically to unforeseen variations in parts, alignment, or environmental conditions. By incorporating real-time data from force, vision, and proximity sensors, the control algorithms can be refined to adjust manipulation parameters on-the-fly, improving the system’s resilience to uncertainty and enhancing its ability to successfully complete complex assembly tasks. Such advancements promise a significant leap in automation capabilities, enabling the creation of systems that are not only faster and more efficient but also remarkably robust and adaptable to the nuances of real-world manufacturing environments.

The advent of macro-micro manipulation signals a potential paradigm shift in modern manufacturing processes. By seamlessly integrating large-scale movements with precise micro-scale adjustments, this approach unlocks the automation of previously inaccessible assembly tasks, paving the way for the creation of increasingly intricate and sophisticated products. This capability extends beyond simple speed improvements – demonstrated by significantly faster assembly times for components like gears and circuit boards – to enable the production of devices with higher density, greater functionality, and improved reliability. The technology promises to reshape industries reliant on precision assembly, fostering innovation in fields ranging from electronics and robotics to medical devices and beyond, ultimately driving a new era of product complexity and performance.

![Bode plots reveal that the identified transfer functions for the macro and micro manipulators-including active and passive sides-demonstrate distinct frequency responses influenced by flexure hinge stiffness, with [latex]k_{\mu,low}[/latex] and [latex]k_{\mu,high}[/latex] values of 15-30 N/mm for the X and Y axes and 20-40 N/mm for the Z axis.](https://arxiv.org/html/2602.01948v1/x4.png)

The presented architecture navigates the inherent complexities of combined macro-micro manipulation with a focus on active compliance, acknowledging that systems, even robotic ones, are not static entities. It’s a design philosophy mirroring the inevitable decay all systems face-the control loop isn’t about preventing disturbance, but gracefully responding to it. As Andrey Kolmogorov observed, “The most important thing in science is not to know, but to search.” This research embodies that search, refining the interaction control loop to increase bandwidth-a version history of iterative improvements, each commit addressing the tax on ambition inherent in achieving precision at multiple scales. The pursuit isn’t merely about force control, but adapting to the medium of time itself.

The Long View

This architecture, while demonstrably effective in augmenting force control bandwidth, merely shifts the locus of complexity. The true challenge isn’t achieving faster reactions, but accepting their inevitable limitations. Systems learn to age gracefully; the pursuit of perpetual responsiveness feels…optimistic. Future iterations will undoubtedly refine the interplay between macro and micro manipulators, perhaps incorporating learning algorithms to anticipate interaction forces. However, a more profound question lingers: at what point does increased precision yield diminishing returns, especially when confronted with the inherent variability of manufacturing processes?

The current framework rightly addresses the deficiencies of leader-follower approaches, but it still assumes a relatively static environment. Real-world applications present dynamic disturbances, unexpected contact, and material properties that defy precise modeling. Perhaps the most fruitful avenue for research lies not in chasing ever-tighter control loops, but in developing systems that are robust to uncertainty-systems that can adapt, yield, and recover from unforeseen circumstances.

Sometimes observing the process-understanding how a system degrades under stress-is better than trying to speed it up. The pursuit of control should not eclipse the wisdom of allowing a system to find its own equilibrium, even if that equilibrium isn’t perfectly aligned with initial specifications. The art lies in recognizing when to guide, and when to simply let be.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.01948.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Heartopia Book Writing Guide: How to write and publish books

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Robots That React: Teaching Machines to Hear and Act

- Mobile Legends: Bang Bang (MLBB) February 2026 Hilda’s “Guardian Battalion” Starlight Pass Details

- UFL soft launch first impression: The competition eFootball and FC Mobile needed

- eFootball 2026 Epic Italian League Guardians (Thuram, Pirlo, Ferri) pack review

- 1st Poster Revealed Noah Centineo’s John Rambo Prequel Movie

- Here’s the First Glimpse at the KPop Demon Hunters Toys from Mattel and Hasbro

- UFL – Football Game 2026 makes its debut on the small screen, soft launches on Android in select regions

- Katie Price’s husband Lee Andrews explains why he filters his pictures after images of what he really looks like baffled fans – as his ex continues to mock his matching proposals

2026-02-03 16:17