Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new study reveals that pretraining language models on abstract procedural data significantly improves their ability to tackle complex tasks and learn more efficiently.

Procedural pretraining enhances algorithmic reasoning and data efficiency in large language models by complementing standard pretraining approaches.

Despite the success of large language models, current pretraining paradigms often lack a structured foundation for acquiring fundamental reasoning skills. This limitation motivates the work ‘Procedural Pretraining: Warming Up Language Models with Abstract Data’, which explores an alternative approach: initializing models with abstract, procedurally generated data. The authors demonstrate that pretraining on such data-ranging from balanced brackets to simple algorithms-significantly improves algorithmic reasoning, data efficiency, and overall performance across diverse tasks, even with minimal exposure. Could this method of ‘warming up’ language models unlock a pathway towards more robust and interpretable knowledge acquisition in LLMs?

Deconstructing the Illusion: Why Language Models Need More Than Statistics

While contemporary Large Language Models demonstrate remarkable proficiency in understanding and generating human-like text – excelling at tasks like translation, summarization, and even creative writing – their capabilities plateau when confronted with problems requiring systematic reasoning or the application of learned knowledge to novel situations. These models often succeed by identifying statistical correlations within vast datasets, allowing them to predict the most probable continuation of a given text, but this approach lacks the robust, rule-based foundation necessary for true generalization. Consequently, even slight deviations from familiar patterns can expose limitations, as the models struggle with abstract concepts, logical deduction, or the consistent application of principles beyond the specific examples encountered during training. This reliance on surface-level patterns, rather than underlying algorithmic structures, represents a significant hurdle in achieving artificial general intelligence.

Current large language models, despite demonstrating remarkable proficiency in tasks involving language comprehension and generation, often falter when confronted with problems requiring systematic reasoning or the ability to generalize beyond observed data. This limitation stems from a fundamental reliance on statistical patterns gleaned from massive datasets, rather than an underlying framework of algorithmic scaffolding. Essentially, these models excel at identifying correlations – predicting the next word in a sequence – but lack the capacity for deductive reasoning or the ability to apply established procedures to novel situations. This means that while a model might accurately complete a pattern it has seen before, it struggles when asked to solve a problem demanding a step-by-step process or the application of a consistent rule, highlighting a critical need to move beyond purely statistical approaches towards architectures that incorporate explicit algorithmic structures.

Building the Algorithmic Skeleton: Procedural Pretraining

Procedural pretraining is a two-stage process wherein a language model first undergoes training on datasets comprised of abstract, structurally-defined data prior to conventional semantic pretraining. This initial phase differs from standard pretraining, which typically utilizes large corpora of natural language text. By exposing the model to data exhibiting inherent algorithmic properties, procedural pretraining aims to establish a foundational skillset in pattern recognition and logical inference before the model encounters the complexities of natural language. The purpose of this staged approach is to improve the model’s capacity for reasoning and problem-solving tasks that require the application of learned algorithms.

Procedural pretraining establishes a base level of algorithmic competency in language models prior to semantic training. This initial phase focuses on developing the model’s capacity for logical inference and problem-solving through exposure to structured, rule-based data. By mastering patterns inherent in abstract procedural data, the model gains an enhanced ability to generalize to novel tasks requiring sequential reasoning, systematic exploration, and the application of learned rules – skills which are then transferable and refined during subsequent semantic pretraining on natural language data.

Abstract data for procedural pretraining is generated through several computational methods. Cellular Automata produce patterns based on local rules applied to a grid, creating complex, evolving structures. Sequence Transformations involve applying defined operations – such as rotations, inversions, or permutations – to initial sequences, generating variations with predictable properties. Simulations of Memory Operations, including read, write, and allocation procedures, generate data reflecting computational state changes. These methods prioritize the creation of data possessing inherent algorithmic structure over semantic meaning, providing a foundation for models to learn procedural reasoning.

The algorithmic structure of procedurally generated datasets is enforced through the use of formal languages. These languages, typically based on established models like context-free grammars or regular expressions, precisely define the permissible sequences and transformations within the data. By specifying rules for data generation, formal languages guarantee consistency and predictability, enabling models to learn underlying algorithmic patterns rather than spurious correlations. This structured approach contrasts with the statistical ambiguities often present in natural language or unstructured image data, providing a controlled environment for initial pretraining and fostering the development of robust problem-solving capabilities.

Bridging the Gap: Integrating Procedural and Semantic Understanding

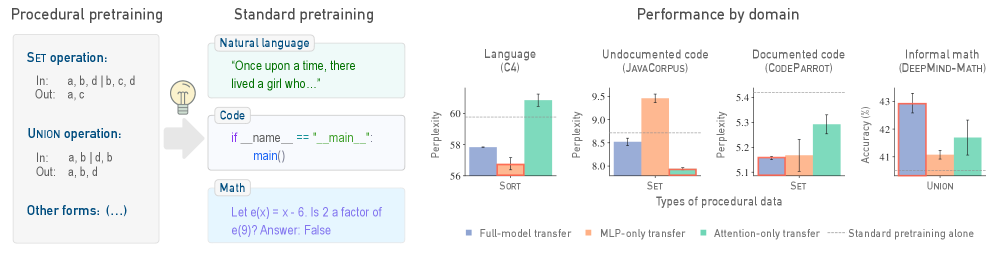

Standard pretraining procedures for large language models typically involve training on extensive corpora of text and code to learn statistical relationships. This work modifies that approach by introducing an initial pretraining stage focused on procedural data – datasets explicitly structured to represent algorithmic or sequential information. This initial procedural pretraining is performed before the standard pretraining on large-scale semantic datasets like C4, CodeParrot, and DeepMind-Math. The intent is to imbue the model with a foundational understanding of algorithmic structures, which then facilitates more efficient learning during subsequent semantic pretraining and improves performance on tasks requiring reasoning capabilities. This staged approach differs from directly mixing procedural and semantic data during a single pretraining phase.

The model’s architecture is designed to integrate information from both semantic and procedural sources. Semantic understanding is derived from large datasets like C4, CodeParrot, and DeepMind-Math, which provide statistical patterns in language and code. Procedural knowledge, representing explicit algorithmic structures, complements this by introducing formalized reasoning steps. This combined approach enables the model to learn not only what information is present in the data, but also how to manipulate and process that information, leading to improved performance on tasks requiring reasoning and problem-solving capabilities.

Evaluations utilizing the GPT-2 architecture demonstrate that pretraining models with procedural data improves performance on reasoning tasks. Specifically, this approach enables comparable performance to standard pretraining methods while reducing the required data volume by up to 45% when utilizing the C4 dataset. This data reduction is achieved through the model’s enhanced ability to generalize from limited examples, indicating a more efficient use of semantic information acquired during pretraining. The observed performance gains suggest that incorporating explicit algorithmic structures alongside statistical patterns improves the model’s capacity for reasoning and problem-solving.

Within the GPT-2 transformer architecture, attention layers and multi-layer perceptron (MLP) layers facilitate the integration of procedural and semantic knowledge. Attention layers allow the model to weigh the importance of different input tokens, enabling it to identify relationships between algorithmic steps and semantic content. The MLP layers, positioned after the attention mechanism, perform non-linear transformations on these weighted representations, further refining the integration of procedural instructions with semantic information derived from datasets like C4, CodeParrot, and DeepMind-Math. This combined process allows the model to leverage both statistical patterns and explicit algorithmic structures, enhancing performance on reasoning tasks by creating interconnected representations of both what needs to be computed and how to compute it.

![Procedural pretraining fosters a modular structure within models, enabling selective transfer of [latex] ext{MLP}[/latex] or attention layers to outperform full-model transfer, as demonstrated by consistent results across ten independent trials (detailed variance in Appendix N.1).](https://arxiv.org/html/2601.21725v1/x3.png)

The Future of Intelligence: Complexity, Mixtures, and Beyond

The inherent complexity of data profoundly impacts a model’s capacity to learn meaningful, generalizable patterns. Data sets possessing lower Kolmogorov Complexity – those describable with fewer computational steps – facilitate the development of robust algorithmic representations because the underlying structure is more readily captured. Conversely, highly complex data, requiring extensive descriptions, presents a greater challenge, potentially leading to overfitting or an inability to discern core principles. This suggests that carefully controlling or characterizing the Kolmogorov Complexity of training data can significantly enhance a model’s ability to learn efficiently and perform reliably across diverse scenarios, moving beyond mere memorization toward true algorithmic understanding.

The capacity for generalization in algorithmic learning is significantly enhanced through techniques like Data Mixtures and Weight Mixtures. These methods strategically combine diverse, procedurally generated datasets, effectively broadening the scope of training data without necessarily increasing its volume. Data Mixtures present the model with examples drawn from multiple procedural sources, while Weight Mixtures allow for a nuanced control over the contribution of each dataset during training – essentially prioritizing certain procedural environments or tasks. This deliberate blending encourages the development of more robust and adaptable algorithms, as the model is exposed to a wider range of scenarios and learns to discern underlying principles rather than memorizing specific instances. The result is a system capable of performing well on unseen data, demonstrating improved performance and a greater capacity for complex reasoning.

The development of procedural data pretraining demonstrates a pathway toward artificial intelligence systems exhibiting enhanced robustness and the capacity for complex reasoning. Current findings indicate that models trained with this methodology can surpass the performance of established baseline models utilizing a surprisingly limited dataset – requiring only 2 to 4 million procedural tokens. This efficiency stems from the structured nature of the data, allowing the AI to learn underlying algorithmic principles rather than simply memorizing patterns. The resulting systems aren’t merely black boxes; their reliance on procedural knowledge offers increased interpretability, enabling a clearer understanding of the reasoning processes behind their outputs and fostering greater trust in their decision-making capabilities.

Researchers anticipate extending this procedural pretraining approach beyond the current focus, investigating its efficacy across diverse data types and artificial intelligence tasks. Initial explorations suggest a significant potential for data efficiency; up to 45% of conventionally used training data could be replaced with this procedurally generated content without compromising performance. This substitution promises not only reduced data acquisition costs and storage requirements but also the opportunity to create more adaptable and generalizable AI systems, less reliant on massive, often biased, static datasets. The methodology’s adaptability hints at a future where AI learning paradigms increasingly prioritize algorithmic understanding and procedural knowledge over sheer data volume.

The exploration of procedural pretraining, as detailed in this work, echoes a fundamental tenet of systems understanding: to truly know a mechanism, one must dissect its underlying logic. It’s a process of reverse-engineering, of identifying the core algorithms that govern behavior. This pursuit aligns with the sentiment expressed by David Hilbert: “We must be able to answer the question: what are the ultimate foundations of mathematics?” The paper’s success in bolstering algorithmic reasoning through abstract data isn’t merely about improving model performance; it’s about probing the very structure of knowledge acquisition, demonstrating that a deeper understanding of procedural logic can unlock greater data efficiency and transfer learning capabilities. Every exploit starts with a question, not with intent, and this research frames a crucial question about how language models ‘think’.

Beyond the Warm-Up: Where Does Procedural Knowledge Lead?

The demonstrated gains from procedural pretraining aren’t simply about smoothing the initial learning curve. One wonders if the observed improvements in algorithmic reasoning stem from the model learning to learn – internalizing a meta-procedure for problem decomposition. If so, the current approach might be a useful, but ultimately limited, heuristic. The real question isn’t whether abstract data helps, but what constitutes genuinely abstract data – and whether the model is identifying the underlying structure, or merely memorizing patterns within the pretraining set. A truly robust system should generalize beyond the specific procedural formats presented.

Current evaluations focus on task performance. However, a more unsettling line of inquiry concerns the model’s internal representation of procedure. Does this pretraining create a ‘ghost in the machine’ – a simulated agent capable of independent algorithmic exploration? Or is it merely a sophisticated pattern-matching engine, skillfully mimicking reasoning without possessing it? Disentangling these possibilities requires probing beyond behavioral outputs, perhaps by examining the activation patterns during procedural processing, and actively seeking instances where the model fails in ways that reveal its underlying assumptions.

The pursuit of data efficiency is laudable, but it shouldn’t eclipse the fundamental question: what is being learned? The current paradigm often treats data as a means to an end – improved performance on benchmarks. But perhaps the true value of abstract procedural data lies not in its utility, but in its ability to reveal the limitations of the learning architecture itself. After all, the most insightful bugs aren’t flaws, but signals – whispers of a deeper, more fundamental constraint.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.21725.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Heartopia Book Writing Guide: How to write and publish books

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Battlestar Galactica Brought Dark Sci-Fi Back to TV

- January 29 Update Patch Notes

- Genshin Impact Version 6.3 Stygian Onslaught Guide: Boss Mechanism, Best Teams, and Tips

- Robots That React: Teaching Machines to Hear and Act

- Learning by Association: Smarter AI Through Human-Like Conditioning

- Mining Research for New Scientific Insights

- Katie Price’s new husband Lee Andrews ‘proposed to another woman just four months ago in the SAME way’

- UFL – Football Game 2026 makes its debut on the small screen, soft launches on Android in select regions

2026-02-01 12:03