Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research uses artificial intelligence to reveal the complex interplay between languages in the human mind.

Language models demonstrate bidirectional processing of shared linguistic structures and asymmetrical transfer from dominant languages, offering insights into crosslinguistic influence.

Despite decades of research, understanding the precise mechanisms of crosslinguistic influence (CLI) in bilingualism remains challenging due to inherent variability in human studies. To address this, we present ‘Language Models as Artificial Learners: Investigating Crosslinguistic Influence’, utilizing language models as controlled statistical learners to systematically simulate and isolate the drivers of CLI. Our findings reveal a hybrid account where shared linguistic structures exhibit bidirectional priming, while the influence of non-shared structures is asymmetrical and sensitive to language dominance and proficiency-factors we manipulate through controlled exposure during model training. Can these computational insights refine existing psycholinguistic theories of bilingual processing and ultimately illuminate the neural basis of crosslinguistic interaction?

The Illusion of Multilingual Mastery

The human capacity for multilingualism presents a significant hurdle for contemporary natural language processing. While current language models excel at tasks within a single language, they often falter when confronted with the nuances of crosslinguistic interaction – instances where one language subtly influences the processing or production of another. This struggle isn’t merely a matter of expanding datasets; it reflects a fundamental gap in how these models represent linguistic knowledge. Humans don’t compartmentalize languages, but rather integrate them, leading to phenomena like code-switching, transfer of grammatical structures, and semantic interference. Consequently, improving a model’s ability to handle these crosslinguistic effects isn’t simply about achieving higher accuracy; it’s about creating systems that more closely mirror the cognitive processes underlying human multilingual competence, paving the way for more robust and genuinely intelligent NLP applications.

Conventional language models typically operate under the assumption of monolingualism, processing each language as a discrete system – a fundamental limitation when attempting to simulate the human brain. This isolated approach overlooks the pervasive phenomenon of crosslinguistic influence, where the knowledge and processing of one language actively shapes the other in bilingual individuals. Studies of bilingual cognition reveal constant interaction – from subtle pronunciation shifts to structural borrowing – demonstrating that languages aren’t stored and utilized in separate compartments. Consequently, traditional models struggle with tasks requiring translation, code-switching, or even understanding nuanced meaning in a bilingual context, as they lack the capacity to represent and leverage the intricate web of connections that characterize the bilingual mind. The result is a performance gap between artificial and human language processing, highlighting the need for models that move beyond isolated language representation.

Current language model training predominantly focuses on monolingual data, inadvertently creating systems that treat languages as separate entities; however, the human bilingual mind doesn’t operate in isolation. A significant advancement requires explicitly modeling crosslinguistic influence (CLI) during the training process – essentially, teaching the model how one language affects the processing of another. This involves incorporating techniques like multilingual training data, where the model is exposed to multiple languages simultaneously, and architectural innovations that facilitate knowledge transfer between them. By simulating the interconnectedness of languages within a single model, researchers aim to overcome the limitations of traditional approaches and create systems that better reflect the cognitive reality of bilingualism, ultimately improving performance on cross-lingual tasks and offering a more nuanced understanding of language processing itself.

![Priming with a second language ([latex]L2[/latex]) yields positive effects on the first language ([latex]L1[/latex]) only when the languages are similar, with minimal impact observed before priming.](https://arxiv.org/html/2601.21587v1/figures/prime_effect_en_l1.png)

Training a Model to Pretend It’s Bilingual

A bilingual training methodology was implemented, concurrently exposing a GPT2 transformer-based language model to data from two languages. This approach deviates from monolingual training and aims to encourage the model to develop shared, crosslinguistic representations of concepts and grammatical structures. By processing text in multiple languages simultaneously, the model is forced to identify and leverage underlying similarities, potentially leading to improved generalization and transfer learning capabilities across languages. The training process utilizes parallel corpora to provide aligned examples in both languages, facilitating the discovery of these crosslingual relationships within the model’s internal representations.

The model’s training leverages the OSCAR Corpus, a large-scale multilingual dataset constructed by crawling Common Crawl and filtering for high-quality text. This corpus provides a diverse and extensive source of data for both languages used in the bilingual training regime. To manage vocabulary efficiently across these languages, the SentencePiece tokenizer is employed. SentencePiece operates by treating text as a sequence of Unicode characters and learns a subword vocabulary, enabling the model to handle rare words and morphologically rich languages effectively, while also minimizing the overall vocabulary size and computational cost.

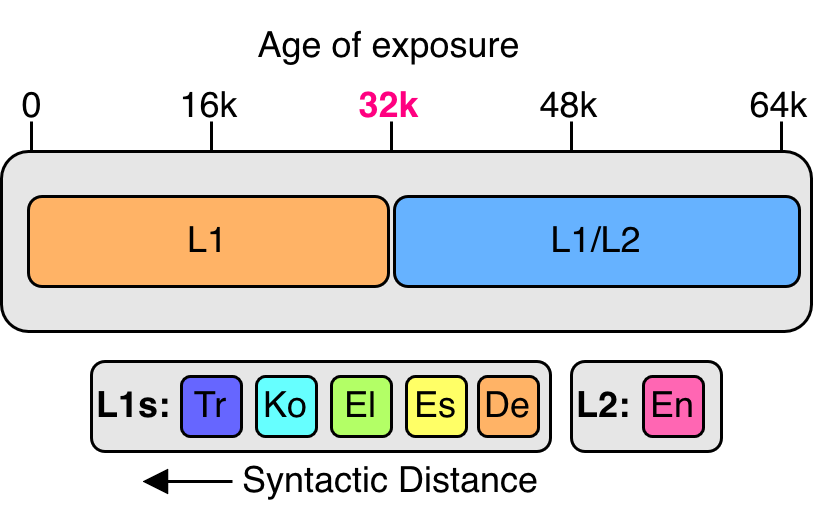

The timing of second language introduction during training significantly impacts a transformer model’s linguistic characteristics, specifically L1 dominance and L2 proficiency. Analysis of hidden states reveals a positive correlation between the age of exposure to the second language and the L1 token ratio within the L2 hidden states; as the second language is introduced later in the training process, the model exhibits a greater reliance on representations derived from the first language. This increased L1 token ratio suggests a stronger entrenchment of the initial linguistic system and a corresponding reduction in the development of independent L2 representations, indicating that earlier exposure promotes a more balanced cross-lingual representation.

![On the BLiMP dataset, the average ratio of [latex]L_1[/latex] to [latex]L_2[/latex] tokens indicates the relative reliance on each language during processing across five different languages.](https://arxiv.org/html/2601.21587v1/figures/logit_lens.png)

Peeking Inside the Machine: Decoding Crosslinguistic Influence

LogitLens is employed as a decoding method to analyze the internal representations of Language Models (LMs) during processing, enabling the quantification of individual language contributions. This technique functions by examining the logit differences – the pre-softmax output layer – to determine the extent to which each language is activated when processing a given input. Specifically, LogitLens measures the contribution of each language’s vocabulary to the LM’s prediction, thereby revealing the degree of crosslinguistic activation occurring within the model’s hidden states. The resulting metrics provide a quantifiable assessment of how and to what extent different languages influence each other during LM processing, moving beyond qualitative observations of crosslinguistic influence.

Crosslinguistic priming is employed to assess how exposure to structures in one language impacts processing in another. To facilitate this, comparable stimuli across languages are generated using the NLLB machine translation model. This process involves translating sentences while preserving syntactic structure, allowing for controlled comparisons of processing times and accuracy. By presenting sentences in one language immediately following a translated, structurally similar sentence in another language, researchers can quantify the degree to which the initial structure facilitates or hinders processing of the subsequent sentence, thereby revealing the presence and magnitude of crosslinguistic influence.

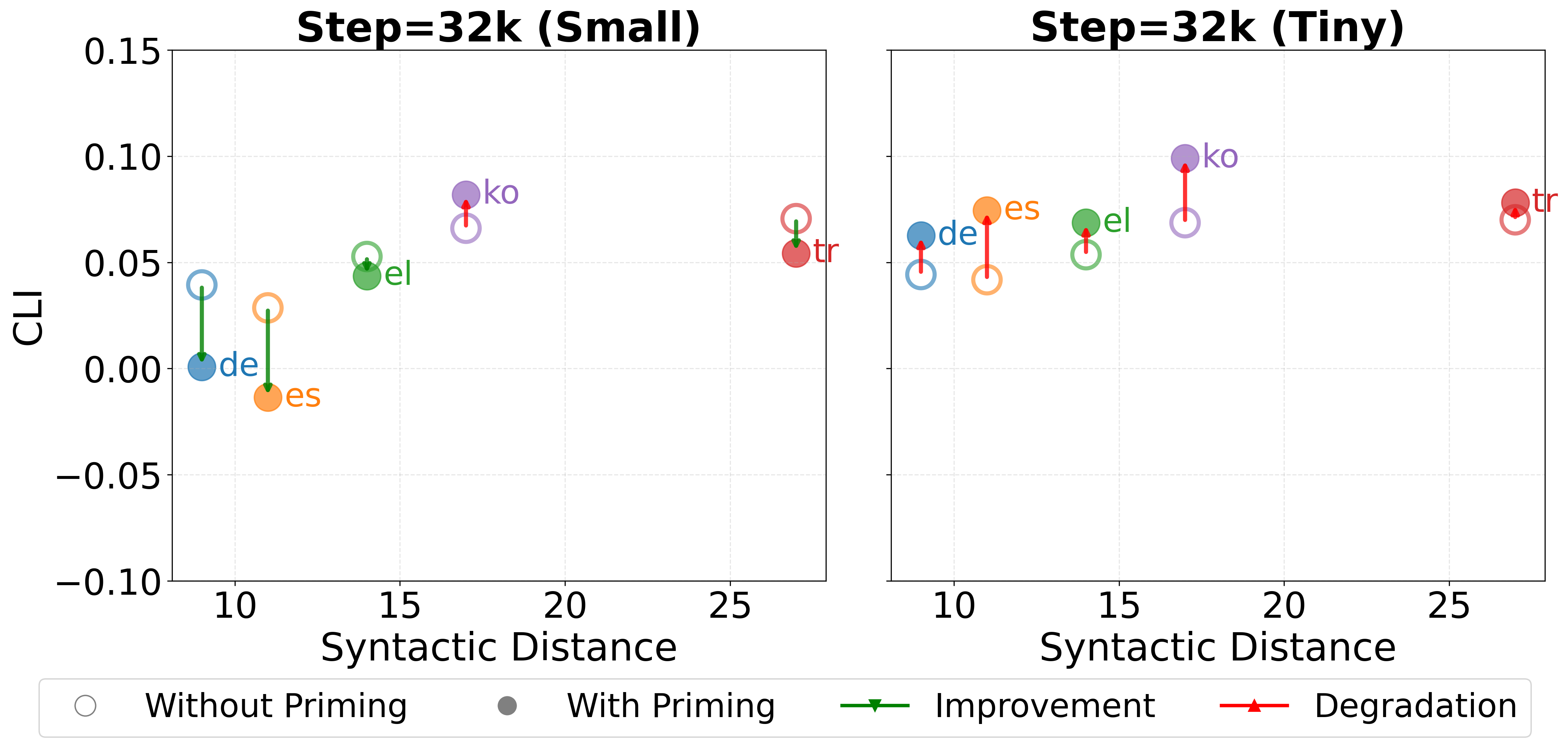

Evaluation using the BLiMP Benchmark and the FCE Dataset demonstrates that Crosslinguistic Influence (CLI) impacts grammatical accuracy and manifests in language-specific patterns. Analysis of accuracy changes with crosslinguistic priming reveals variation correlated with syntactic distance; German and Spanish exhibit positive transfer, improving performance on 9 and 7 phenomena respectively on the BLiMP benchmark, while Turkish and Korean demonstrate negative transfer, improving performance on only 2 and 3 phenomena respectively. These results provide quantitative evidence for CLI, indicating that the effect is not uniform across languages and is influenced by the structural differences between them.

![Priming with larger NLLB models ([latex]1.3B[/latex] and [latex]3.3B[/latex]) effectively mitigates catastrophic language interference (CLI) similarly to the [latex]600M[/latex] model across various languages.](https://arxiv.org/html/2601.21587v1/figures/prime_effect_nllb_3b.png)

The Illusion of a Unified Linguistic System

Current research into how large language models (LMs) represent multiple languages suggests a nuanced picture beyond simple unification or separation. Investigations reveal that these models don’t necessarily adhere to a single representational strategy; instead, they demonstrate characteristics consistent with both the Shared Syntax Hypothesis and the Separate-but-Connected Syntax. This implies LMs can, in effect, leverage a unified underlying structure for languages with considerable overlap, while simultaneously maintaining distinct, yet interconnected, modules for those that diverge significantly. The capacity to dynamically shift between these representational modes suggests a sophisticated adaptability, allowing the model to efficiently process and generate text across a variety of linguistic structures and highlighting a more flexible architecture than previously assumed.

The extent to which languages share word order significantly impacts how a language model represents them, alongside the overall structural differences – or syntactic distance – between those languages. Research indicates that greater overlap in word order encourages the model to utilize shared linguistic representations, effectively treating both languages through a unified grammatical framework. Conversely, when languages exhibit substantial differences in syntax, the model increasingly relies on separate, yet interconnected, representations, dedicating distinct neural pathways to process each language’s unique structure. This suggests Cross-Linguistic Influence (CLI) isn’t a simple ‘shared versus separate’ scenario, but a dynamic process where linguistic similarity and dissimilarity act as modulating forces, shaping the model’s architectural biases and ultimately determining the degree of shared or independent processing.

Cross-linguistic influence (CLI) within large language models is not a singular process, but emerges from the intricate interaction of linguistic characteristics and the model’s inherent architectural design. Research indicates that the extent of CLI varies depending on factors like word order similarities and the syntactic distance between languages; as the structural differences increase, the number of neurons uniquely dedicated to the second language diminishes. This reduction in neuron overlap directly correlates with observed changes in CLI, suggesting that the model increasingly relies on separate, rather than shared, representations as languages diverge syntactically. Consequently, the study highlights a nuanced understanding of how language models process multiple languages, demonstrating that CLI is a dynamic phenomenon shaped by both linguistic input and the model’s internal organization.

The study meticulously maps bidirectional influence between languages, finding shared structures facilitate transfer while dissimilar ones don’t-a neat observation, though it feels like charting the inevitable decay of any system. Brian Kernighan once noted, “Debugging is twice as hard as writing the code in the first place. Therefore, if you write the code as cleverly as possible, you are, by definition, not smart enough to debug it.” This feels eerily applicable. The researchers attempt to model language acquisition, but they’re really just documenting how initial simplicity-a native tongue-becomes increasingly convoluted by the addition of new rules and exceptions. They’ll call it ‘crosslinguistic influence’ and publish a paper; the underlying truth is that every language model, like every codebase, accumulates tech debt-emotional debt with commits-as it attempts to represent the messy reality of human communication.

What’s Next?

The assertion that language models can meaningfully simulate crosslinguistic influence feels, predictably, like a step toward automating the very problems that plague computational linguistics. This work highlights bidirectional processing for shared structures – a neat result, though one suspects production systems will rapidly discover edge cases where that symmetry collapses. The asymmetrical transfer observed in non-shared structures merely formalizes a truth known to polyglots: some linguistic baggage is heavier than others. Future iterations will inevitably involve more languages, larger models, and more meticulously curated datasets – each addition a new layer of abstraction built on foundations of statistical correlation.

The current framework treats linguistic distance as a measurable variable. However, ‘distance’ is rarely Euclidean. Cultural context, communicative intent, and the sheer messiness of real-world usage are conveniently ignored. The pursuit of a universally applicable model risks distilling language into a sterile, quantifiable entity, losing sight of the fact that language evolves to solve messy, unpredictable problems. The next step isn’t necessarily better models, but more honest acknowledgement of their limitations.

Ultimately, this research, like all research, is a temporary reprieve from entropy. The models will become outdated. The datasets will prove incomplete. The ‘elegant’ solutions will become tomorrow’s tech debt. But for now, it offers a useful – if fleeting – glimpse into the black box, and provides more fuel for the inevitable race to build increasingly complex systems that will, inevitably, break in surprising and frustrating ways. CI is the temple – one prays nothing breaks.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.21587.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Heartopia Book Writing Guide: How to write and publish books

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Battlestar Galactica Brought Dark Sci-Fi Back to TV

- January 29 Update Patch Notes

- Genshin Impact Version 6.3 Stygian Onslaught Guide: Boss Mechanism, Best Teams, and Tips

- Learning by Association: Smarter AI Through Human-Like Conditioning

- Mining Research for New Scientific Insights

- Robots That React: Teaching Machines to Hear and Act

- Nature’s GPS: AI Learns to Navigate Like an Insect

- 1st Poster Revealed Noah Centineo’s John Rambo Prequel Movie

2026-02-01 07:16