Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research suggests that coordinating multiple smaller AI agents with access to tools can achieve superior reasoning capabilities compared to relying on a single, extremely large language model.

This study demonstrates that tool-augmented, multi-agent systems can surpass larger monolithic models on complex tasks, though the benefits of explicit reasoning steps are context-dependent.

Despite the prevailing trend towards increasingly larger language models, a fundamental question remains regarding the efficacy of scale versus intelligent architecture. This paper, ‘Can Small Agent Collaboration Beat a Single Big LLM?’, investigates whether smaller, tool-augmented agents can surpass the performance of monolithic models on complex reasoning tasks using the GAIA benchmark. Results demonstrate that equipping \mathcal{N}=4B parameter models with tools enables them to outperform larger \mathcal{N}=32B models, though the benefits of explicit reasoning-such as planning-are highly dependent on task configuration and can destabilize tool use. Will this approach of collaborative, tool-augmented agents redefine the optimal path towards artificial general intelligence?

The Inevitable Limits of Scale

Despite their remarkable ability to generate human-quality text, traditional Large Language Models frequently falter when presented with reasoning challenges requiring multiple sequential steps. This isn’t simply a matter of insufficient data or training; the very foundation of these models – predicting the next token in a sequence – proves inadequate for tasks demanding genuine inference. While adept at recognizing patterns within existing data, LLMs struggle to extrapolate beyond that data or to reliably maintain context across extended reasoning chains. The inherent architecture prioritizes statistical correlation over logical deduction, meaning that even seemingly coherent responses can be built on spurious connections rather than sound reasoning, ultimately revealing a fundamental limitation in their capacity for complex problem-solving.

Current research indicates that increasing the size of large language models does not consistently translate to improved reasoning capabilities. A study revealed a compelling disparity: a 4 billion parameter model, when structured with an agentic architecture-allowing it to utilize tools and break down problems into manageable steps-demonstrated superior performance compared to a significantly larger 32 billion parameter model lacking such a framework. This suggests that inherent architectural inefficiencies within traditional LLMs limit their ability to handle complex reasoning, and that a fundamental shift toward more structured, tool-augmented approaches is crucial for developing genuinely intelligent AI agents, rather than simply relying on brute-force scaling of parameters.

The growing need for dependable AI agents is driving a critical reassessment of current development strategies. While increasing the size of large language models has yielded impressive results in some areas, it’s becoming increasingly clear that sheer scale isn’t a sustainable path to robust reasoning capabilities. A fundamental shift is required, prioritizing the development of more structured and efficient reasoning mechanisms within these agents. This means moving beyond simply memorizing and regurgitating information, and instead focusing on architectures that allow AI to systematically break down problems, evaluate potential solutions, and learn from its mistakes-approaches that mimic the cognitive processes of more adaptable intelligence and ultimately deliver truly reliable performance.

Deconstructing Intelligence: Architectures of Explicit Thought

Agentic AI systems address limitations of traditional, monolithic AI models by separating the reasoning process from a single, large parameter set. This is achieved through an Agentic Reasoning Framework, which structures problem-solving as a series of orchestrated steps executed by distinct ‘agents’. These agents are not necessarily individual models, but rather functional components within a larger system designed to handle specific sub-tasks. Decoupling reasoning allows for greater modularity, improved interpretability, and facilitates the integration of external tools and knowledge sources. The framework enables dynamic task decomposition and adaptation, permitting the system to address complex challenges that would be intractable for a single, undifferentiated model.

Agentic AI systems utilize ‘Explicit Thinking’ techniques to manage complexity by decomposing tasks into discrete, sequential steps. Planner-Style Decomposition involves an initial phase of high-level planning where the system outlines the necessary actions to achieve a goal, creating an executable plan. Complementing this, Chain-of-Thought Prompting encourages the model to articulate its reasoning process at each step, detailing the logic behind its actions. This explicit articulation facilitates error analysis and improves the transparency of the decision-making process, allowing for more reliable and interpretable results as the system progresses through the defined sequence of operations.

Agentic systems enhance problem-solving capabilities by integrating planning algorithms with the ability to invoke external tools. This combination allows the system to not only decompose a complex challenge into manageable steps-as determined by the planning component-but also to execute those steps using specialized tools for tasks like data retrieval, calculation, or API interaction. Tool invocation expands the agent’s operational scope beyond the limitations of its core model, enabling it to access and process information dynamically. Consequently, these systems can address intricate challenges requiring external knowledge or specific functionalities, leading to more robust and accurate solutions compared to systems reliant solely on internal parameters.

Extending the Mind: Tool-Augmentation and the Limits of Parametric Knowledge

Tool-augmented language models address limitations of standalone large language models by integrating access to external functionalities. These models don’t solely rely on their pre-trained parameters but can dynamically utilize tools for tasks such as web searching and code execution. Web search capabilities enable agents to retrieve current information beyond the model’s knowledge cutoff, while code execution allows for complex computations and data manipulation. This external tool access significantly improves performance on tasks requiring up-to-date information or calculations, effectively extending the model’s reasoning capacity and enabling it to handle a broader range of problems.

Large language models (LLMs) possess inherent limitations regarding access to current information and computational ability. Agents address these constraints by integrating external tools, notably the Web Search Agent and the Coding Agent. The Web Search Agent facilitates information retrieval from the internet, allowing agents to access data beyond their training cutoff and respond to queries requiring up-to-date knowledge. Simultaneously, the Coding Agent enables agents to perform complex calculations, data analysis, and algorithmic tasks that are outside the scope of their parametric knowledge. This tool utilization effectively extends the agent’s capabilities, allowing it to solve problems requiring both external data and computational processing, thereby mitigating the limitations of relying solely on pre-trained model parameters.

The Mind-Map Agent addresses the limitations of fixed-context language models by constructing dynamic knowledge graphs from input data. This agent processes information and represents it as nodes and edges, establishing relationships between concepts and allowing for efficient traversal and retrieval of relevant details, even within extensive inputs. By organizing information in this manner, the Mind-Map Agent enables more informed decision-making as it can effectively manage and utilize long-context data, overcoming the constraints of traditional sequence-based processing and improving reasoning capabilities.

GAIA: A Benchmark for Agency, Not Just Accuracy

The GAIA Benchmark serves as a comprehensive platform for assessing the capabilities of agentic systems, deliberately designed to challenge them with tasks of escalating complexity. This evaluation framework moves beyond simple accuracy metrics to probe an agent’s ability to reason, plan, and utilize tools effectively – crucial components of true agency. By presenting scenarios requiring diverse skill sets, GAIA not only quantifies performance but also highlights the strengths and weaknesses of different agentic architectures. The benchmark’s tiered difficulty allows researchers to pinpoint the limits of current systems and track progress as new models and techniques emerge, fostering a more nuanced understanding of artificial intelligence’s evolving problem-solving abilities.

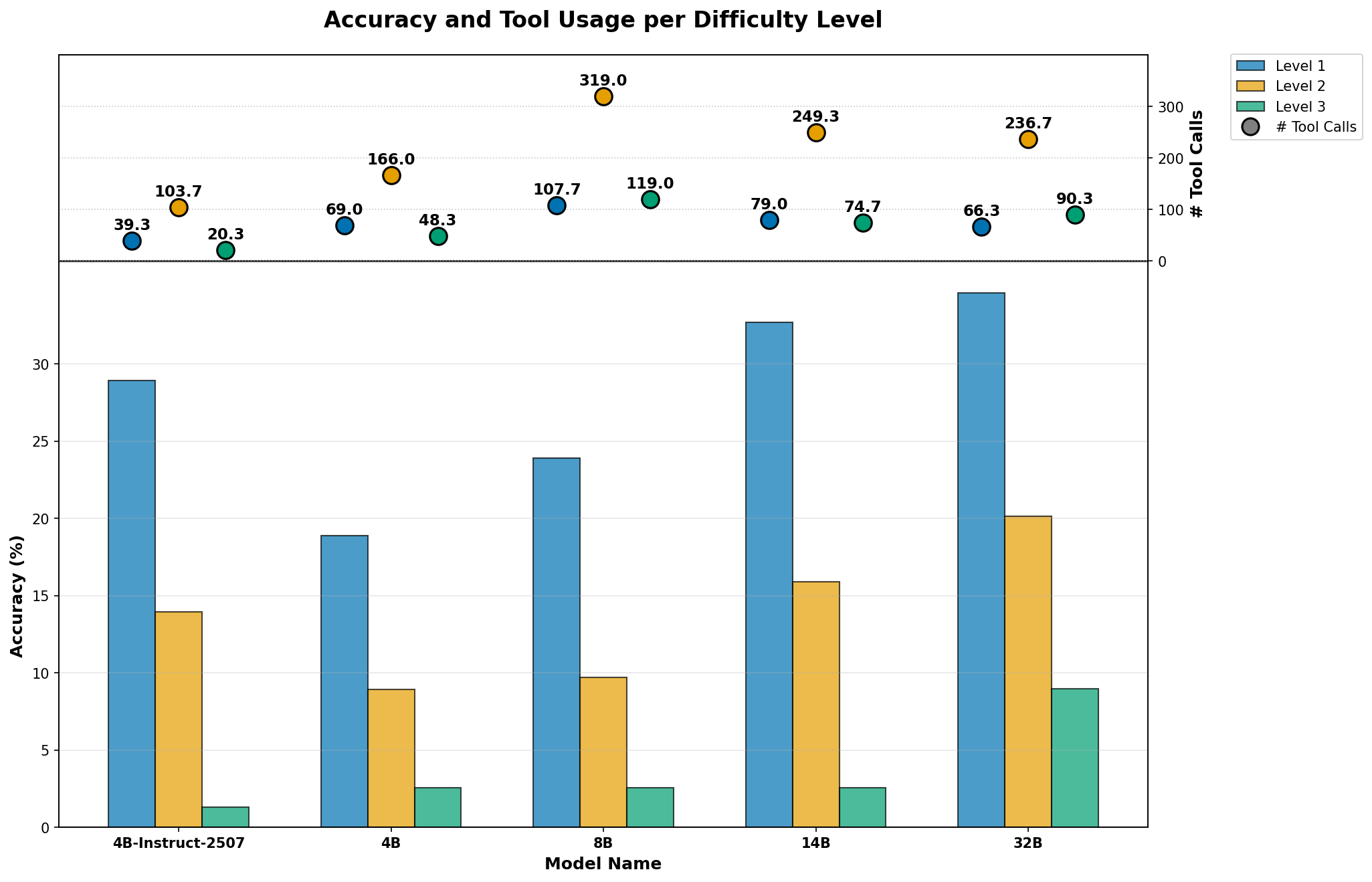

Quantifiable metrics are central to understanding the efficacy of agentic systems, and comparative analyses reveal surprising performance dynamics. Studies utilizing the GAIA Benchmark demonstrate that architectural choices can outweigh sheer model size; specifically, a 4 billion parameter model, when implemented with an agentic framework allowing tool use, achieves an 18.18% accuracy rate. This result notably surpasses the 12.73% accuracy attained by a significantly larger, 32 billion parameter model operating without such tools. These findings underscore the importance of evaluating not only absolute performance, but also the interplay between model scale, agentic capabilities, and the strategic implementation of external tools for problem-solving, offering a clear pathway for iterative refinement and optimization of these systems.

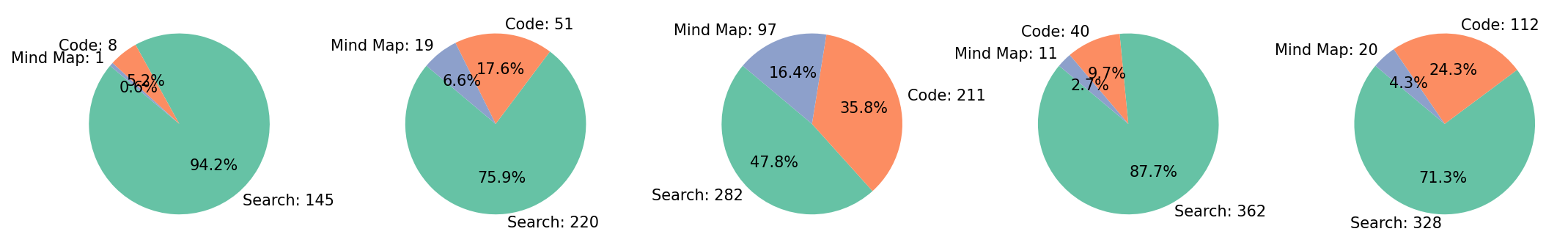

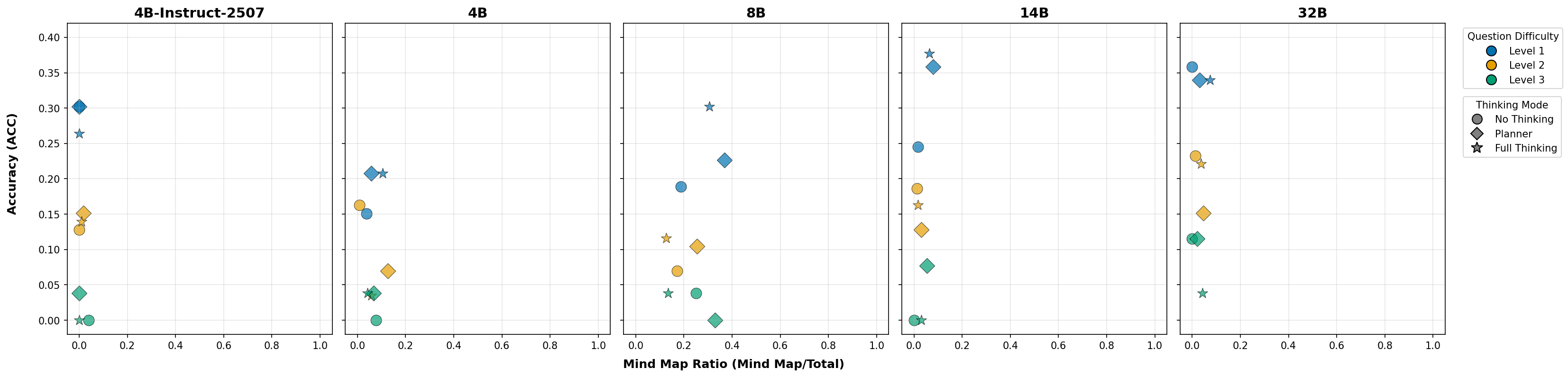

Investigations utilizing Qwen3 Models, enhanced through instruction tuning, reveal substantial gains in agentic task performance. A 32 billion parameter model, when configured with an agentic framework, achieved an accuracy rate of 25.45%; while enabling a ‘full thinking’ process-allowing the model to more thoroughly articulate its reasoning-slightly decreased this to 23.03%. Notably, an 8 billion parameter model demonstrated even more pronounced benefits from the agentic approach, reaching 16.36% accuracy with both agentic setup and full thinking, a significant improvement over its 10.30% accuracy when performing tasks without explicit reasoning steps; these findings underscore the potential of combining refined language models with agentic architectures to unlock improved problem-solving capabilities, even with smaller parameter counts.

Towards a Collaborative Future: Beyond Monoliths

The development of multi-agent collaboration marks a crucial step forward in artificial intelligence, moving beyond monolithic systems to distributed networks of specialized components. This architectural shift allows for the decomposition of complex problems into manageable sub-tasks, each handled by an agent optimized for a specific function. By distributing the reasoning process, these systems not only enhance computational efficiency but also demonstrate improved robustness; if one agent encounters an issue, others can compensate, preventing total system failure. This approach mirrors the efficiency of biological systems and promises to unlock solutions to problems previously intractable for single, centralized AI, ultimately paving the way for more resilient and capable artificial intelligence.

The integration of multiple, specialized AI agents offers a pathway to significantly enhanced problem-solving capabilities. Rather than relying on a single, monolithic system, this approach distributes cognitive load, allowing each agent to focus on its area of expertise. This division of labor not only accelerates processing speeds – as components operate in parallel – but also improves the accuracy of results by leveraging the unique strengths of each agent. Consequently, previously intractable challenges in fields like robotics, data analysis, and complex system control become increasingly accessible, opening doors to innovative applications and a new generation of intelligent systems capable of tackling real-world complexity with greater finesse and efficiency.

The trajectory of artificial intelligence is increasingly focused on systems built not as monolithic entities, but as interconnected networks of specialized modules. This architectural shift towards modularity and collaboration offers a pathway to overcome limitations inherent in traditional AI design. By distributing complex problem-solving across multiple agents, each optimized for a specific subtask, these systems exhibit enhanced adaptability to novel situations and improved scalability to handle ever-increasing data volumes. Furthermore, this collaborative approach mirrors the efficiency and robustness observed in natural intelligence, suggesting that such designs are not merely a technological advancement, but a fundamental step towards creating truly intelligent systems capable of learning, evolving, and responding to the world with greater nuance and effectiveness.

The study reveals a curious truth about complex systems – scaling size isn’t always the answer. The pursuit of ever-larger monolithic models feels increasingly like building more elaborate towers on shaky foundations. Andrey Kolmogorov observed, “The most important discoveries are often the simplest.” This sentiment resonates deeply with the findings presented; the paper demonstrates that strategically combining smaller, tool-augmented agents can achieve superior results on the GAIA benchmark. It’s not about brute force, but about emergent behavior arising from carefully orchestrated interactions. The research subtly suggests that architectural choices, even those prioritizing distributed reasoning, inevitably shape the system’s eventual fate-a prophecy of either resilience or cascading failure.

The Turning of the Wheel

The observation that smaller, collaborative agents can eclipse larger, singular models isn’t a surprise, merely a confirmation. Every dependency is a promise made to the past, and here, that past is the distributed nature of intelligence itself. The challenge, of course, isn’t achieving parity with a monolithic model, but understanding how this emergent behavior arises. The current work suggests explicit thinking isn’t universally beneficial-a gentle reminder that architectures aren’t solutions, but prophecies of future failure. The pursuit of ‘reasoning’ as a discrete component feels increasingly like attempting to map the ocean by labeling each drop.

The field now finds itself circling a crucial question: can these agentic ecosystems be grown, or must they always be painstakingly built? The tendency to optimize for benchmarks – even sophisticated ones like GAIA – will inevitably reveal local maxima. True progress lies in fostering conditions for adaptation, for self-repair. Everything built will one day start fixing itself, and the most resilient systems will be those that anticipate this inevitability.

Control is an illusion that demands SLAs. The focus shouldn’t be on dictating behavior, but on cultivating robustness. The real work isn’t in making agents ‘think’ better, but in designing the substrate upon which intelligence – in all its unpredictable glory – can flourish. The wheel turns, and the questions remain remarkably consistent, only the tools change.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.11327.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Clash Royale Best Boss Bandit Champion decks

- Vampire’s Fall 2 redeem codes and how to use them (June 2025)

- Best Arena 9 Decks in Clast Royale

- World Eternal Online promo codes and how to use them (September 2025)

- Country star who vanished from the spotlight 25 years ago resurfaces with viral Jessie James Decker duet

- ‘SNL’ host Finn Wolfhard has a ‘Stranger Things’ reunion and spoofs ‘Heated Rivalry’

- JJK’s Worst Character Already Created 2026’s Most Viral Anime Moment, & McDonald’s Is Cashing In

- Solo Leveling Season 3 release date and details: “It may continue or it may not. Personally, I really hope that it does.”

- Kingdoms of Desire turns the Three Kingdoms era into an idle RPG power fantasy, now globally available

- M7 Pass Event Guide: All you need to know

2026-01-20 15:51