Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research sheds light on the internal workings of Mixture-of-Experts models, revealing how specialized components contribute to overall performance.

This study identifies ‘domain experts’ and ‘driver experts’ within MoE architectures using activation entropy and causal analysis to improve interpretability and efficiency.

While significant progress has been made in understanding Transformer-based language models, the specialized roles of experts within Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) architectures remain largely unexplored. This work, ‘What Gets Activated: Uncovering Domain and Driver Experts in MoE Language Models’, addresses this gap by identifying ‘domain experts’-those favoring specific content-and ‘driver experts’-those most influential on model output. Through metrics assessing activation entropy and causal effect, we demonstrate that certain experts exhibit clear content preferences while others exert disproportionate control over performance, and that early tokens often trigger the activation of these key drivers. How can a deeper understanding of these internal mechanisms not only enhance model interpretability but also unlock substantial performance gains across diverse applications?

Scaling Limits and the Rise of Sparse Models

Conventional dense transformer models, renowned for their capabilities in natural language processing, encounter a fundamental limitation as sequence lengths and model dimensions grow. This arises from the attention mechanism, where each token must be compared to every other token in the sequence – a process demanding computational resources and memory that scale quadratically with the input size O(n^2). Consequently, doubling the sequence length necessitates quadrupling the computational cost, rapidly becoming prohibitive for processing lengthy documents or tackling complex reasoning tasks. This quadratic scaling presents a significant barrier to deploying these powerful models on resource-constrained devices or scaling them to handle the ever-increasing volumes of data in modern applications, prompting researchers to explore alternative architectures that mitigate this fundamental bottleneck.

The limitations imposed by quadratic scaling significantly impede the capacity of traditional dense transformer models to undertake sophisticated reasoning tasks and effectively utilize large datasets. As sequence lengths and model dimensions increase, the computational demands – specifically the number of parameters and required memory – grow exponentially. This presents a critical bottleneck, preventing these models from fully leveraging the benefits of scale and hindering their ability to discern subtle patterns or draw inferences from extensive knowledge. Consequently, the potential for improved performance in areas such as natural language understanding, complex problem-solving, and knowledge-intensive applications remains unrealized due to these inherent computational constraints, driving the pursuit of more efficient architectural designs.

Recognizing the limitations of traditional dense transformer models, researchers have increasingly turned to sparse architectures, with the Mixture of Experts (MoE) emerging as a prominent approach. Unlike dense models where every parameter processes every input, MoE layers strategically activate only a subset of parameters – specifically, a few “expert” networks – for each input token. This conditional computation dramatically reduces the computational cost, allowing models to scale to trillions of parameters without a proportional increase in processing demands. By distributing the parameter load and focusing computation on relevant parts of the model, MoE architectures unlock the potential for handling significantly longer sequences and more complex reasoning tasks, representing a crucial step towards more efficient and powerful artificial intelligence systems.

Introducing Sparse MoE: Selective Computation and Scalability

Sparse Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) models mitigate scaling limitations in large neural networks by employing conditional computation. Rather than activating all parameters for every input, these models selectively engage only a fraction of the total parameters. This is achieved by routing each input token to a limited number of expert modules, thereby reducing the computational burden. Specifically, if a model contains N total parameters and M experts, with each input routed to k experts, the computation per token is approximately equivalent to a model with k <i> M parameters, significantly less than N when N >> k </i> M. This selective activation directly translates to lower FLOPs and memory requirements during both training and inference, enabling the creation of substantially larger models without a corresponding proportional increase in computational cost.

The functionality of Sparse MoE models relies on a Gating Network that performs token-to-expert assignment. This network receives input tokens and generates weights indicating the relevance of each token to each available Domain Expert module. Instead of processing each token through all experts, the gating network selects only the k top-weighted experts for each token – a process known as conditional computation. This dynamic routing is implemented using a softmax function over the experts, and the selected experts then process their assigned tokens in parallel, reducing overall computational load while enabling specialization.

Sparse Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) architectures improve scalability by decoupling model capacity from computational cost. Traditional dense models require all parameters to be processed for each input, leading to quadratic increases in computation with model size. In contrast, Sparse MoE models activate only a small subset of parameters – the experts – for any given input token. This selective activation, guided by a gating network, allows for increasing the total number of parameters, and thus model capacity, without a corresponding linear increase in computational requirements during inference or training. Consequently, Sparse MoE models can achieve higher performance with a more efficient use of computational resources, enabling the training of significantly larger models.

Unveiling Expert Specialization and Routing Strategies

The `Routing Gate` in Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) models employs techniques such as `Top-k Routing` to distribute computation efficiently. Instead of sending each input token to all experts, `Top-k Routing` selects only the k most relevant experts for each token, based on the token’s compatibility with each expert’s weights. This dramatically reduces the computational cost per token, as only a subset of the total expert parameters are activated. The value of k is a hyperparameter controlling the sparsity of expert activation; lower values of k increase sparsity and reduce computation but may limit the model’s ability to capture complex relationships, while higher values approach a dense model. The selection process is typically based on a learned scoring function within the `Routing Gate` that quantifies the relevance of each expert to the given token, ensuring that tokens are directed to the experts most capable of processing them.

Activation Rate, calculated as the proportion of input tokens routed to a specific expert, indicates the expert’s level of specialization – a higher rate suggests the expert handles a larger share of the input distribution. Complementing this, Activation Entropy measures the diversity of tokens an expert processes; lower entropy indicates the expert consistently handles a narrow subset of tokens, reinforcing specialization. Specifically, Entropy = - \sum_{i} p_i \log p_i, where p_i is the probability of the i-th token being routed to the expert. Together, these metrics provide quantifiable insights into how effectively an expert focuses on particular aspects of the input data, allowing for analysis of model capacity utilization and potential imbalances in expert workload.

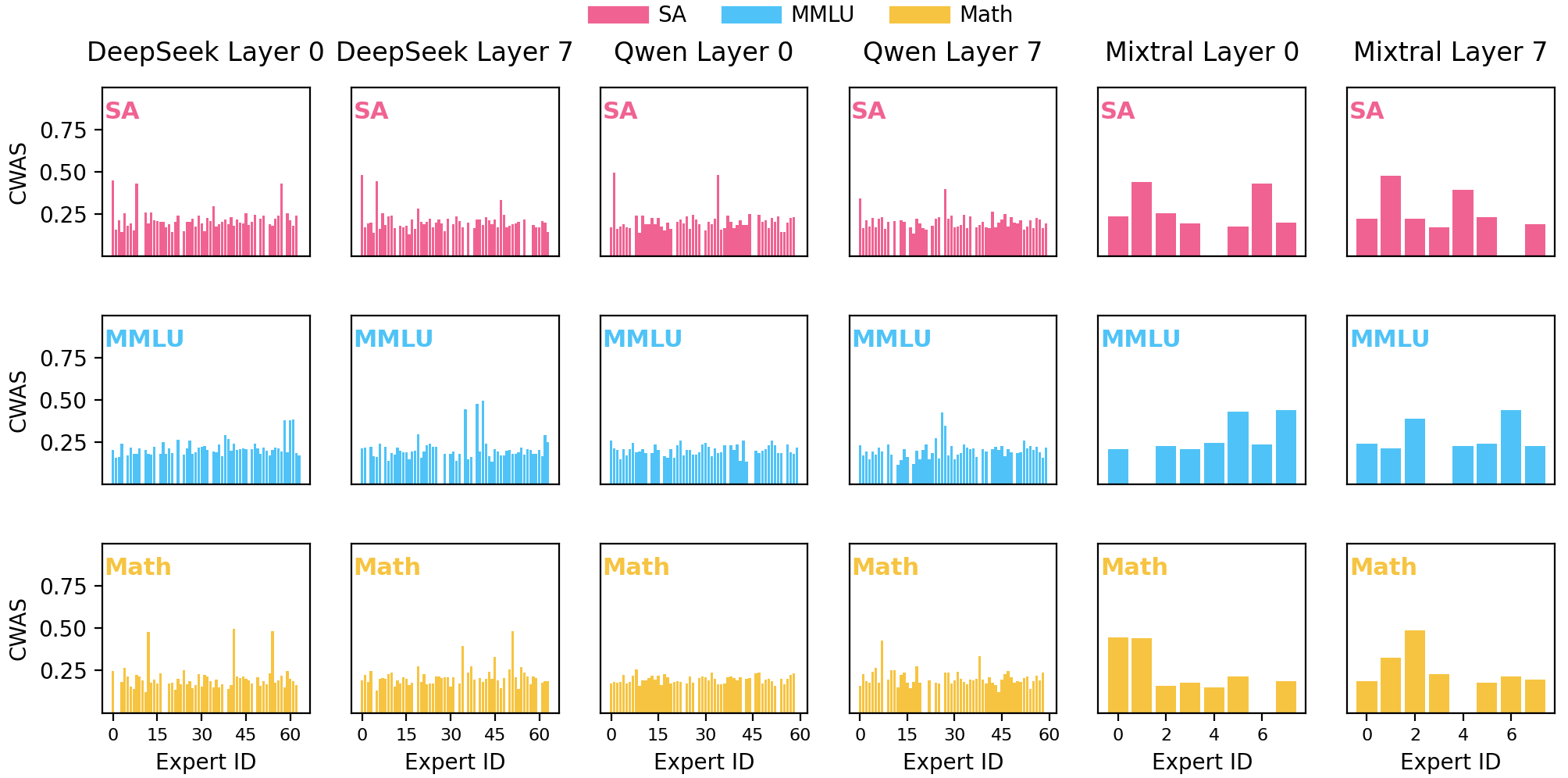

The Certainty-Weighted Activation Score is calculated by combining an expert’s Activation Rate – the frequency with which the expert is selected for processing a token – with its Activation Entropy, which quantifies the confidence or randomness of that selection; lower entropy indicates higher confidence. This combined score provides a single metric for evaluating expert performance, effectively weighting both the frequency of activation and the consistency of that activation. A high score indicates an expert is frequently and confidently engaged, signifying a valuable contribution to the model’s processing, while a low score suggests either infrequent use or inconsistent, potentially unreliable, activation patterns. This score facilitates targeted tuning and optimization of individual experts within a Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) architecture.

Deciphering Causal Influence and Optimizing Expert Contributions

Pinpointing ‘driver experts’ within a mixture-of-experts (MoE) model is fundamental to deciphering its complex decision-making processes. These specialized modules, rather than contributing equally, often disproportionately influence the final output; identifying them allows us to understand why a model generates a particular response. This isn’t simply about observing which experts activate – it’s about determining which ones are truly steering the prediction. The ability to isolate these ‘driver experts’ offers a pathway to model interpretability, enabling a focused analysis of the knowledge and reasoning embedded within specific parts of the network, and ultimately improving trust and control over large language model behavior.

Determining the precise contribution of individual experts within a Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) model requires more than simply observing their activation rates. Causal Effect Estimation offers a rigorous approach by systematically evaluating model performance both with and without the participation of a specific expert. This is achieved through a controlled comparison: the model predicts an outcome using all experts, then again with the target expert’s contribution removed or masked. The difference in these predictions, measured using metrics like Kullback-Leibler Divergence, reveals the magnitude of that expert’s causal influence – essentially, how much the model’s output changes as a direct result of its involvement. This technique moves beyond correlation to establish a clearer understanding of which experts are truly driving performance, offering valuable insights for model refinement and targeted optimization.

To rigorously determine each expert’s contribution within a Mixture of Experts (MoE) model, researchers employ Kullback-Leibler (KL) Divergence – a metric quantifying the difference between probability distributions. This isn’t simply assessing whether an expert changes a prediction, but rather how much the overall probability distribution shifts with and without its input. Specifically, KL divergence measures the information lost when one probability distribution is used to approximate another; in this context, it reveals how much ‘surprise’ or difference arises in the model’s output when a particular expert is excluded. A higher KL divergence indicates a more substantial impact – a greater causal effect – demonstrating that the expert significantly alters the model’s predictive behavior. D_{KL}(P||Q) = \sum_{i} P(i) \log \frac{P(i)}{Q(i)} This precise quantification of causal effects, facilitated by KL divergence, allows for targeted tuning of expert weights and ultimately improves model performance.

Refining the contribution of specialized experts within Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) large language models demonstrably improves performance. Research indicates that carefully adjusting the weights assigned to both domain-specific and ‘driver’ experts-those pivotal in shaping model outputs-results in average accuracy gains of 2.08% and 3.00% respectively, across three distinct MoE LLMs. This highlights the practical benefits of task-aware expert activation, suggesting that a nuanced approach to weighting these specialized modules allows models to more effectively leverage their collective knowledge and enhance predictive capabilities. The observed improvements underscore the potential for further optimization through intelligent weighting strategies, moving beyond uniform activation to a more discerning allocation of expertise.

The study of Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) models reveals a complex interplay of specialized components, mirroring the interconnectedness of systems where structure dictates behavior. Identifying ‘driver experts’ and ‘domain experts’ isn’t merely about pinpointing active neurons; it’s recognizing how these components collectively contribute to the model’s overall function. This echoes a fundamental principle of elegant design-clarity emerges from understanding the whole. As Blaise Pascal observed, “The eloquence of the body is in the muscles.” Just as coordinated muscular action produces graceful movement, the orchestrated activation of experts within an MoE model determines its capacity for nuanced language processing. Every simplification in model architecture, therefore, has a cost, and understanding these trade-offs is crucial for building truly effective systems.

Where the Network Leads

The identification of ‘domain’ and ‘driver’ experts within Mixture-of-Experts models offers a tempting illusion of control. It is easy to envision a future of surgically precise interventions, optimizing individual expert contributions for specific tasks. However, the ecosystem remains complex. Focusing solely on individual expert performance neglects the emergent properties arising from their interactions – the subtle negotiations, the redundancies, and the unexpected synergies that define a functioning whole. A truly scalable solution will not come from brute-force optimization of parts, but from understanding the principles governing the network’s self-organization.

Current metrics, while insightful, remain proxies for a deeper understanding of causal mechanisms. Activation entropy, for example, signals importance, but does not reveal the nature of that importance. Future work must move beyond correlation and towards true causal inference – discerning how changes in one expert’s behavior reliably affect the system’s overall output. This necessitates a shift from observational analysis to controlled experimentation, perhaps employing techniques borrowed from dynamical systems theory.

The pursuit of interpretability is often framed as a quest to ‘open the black box’. But perhaps the box is not meant to be opened, only understood. A complex system does not yield its secrets through dissection, but through careful observation of its behavior. The task, then, is not to illuminate the inner workings, but to model the network’s external responses – to predict, with increasing accuracy, how it will react to novel stimuli. This is not about knowing what is activated, but how it scales.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.10159.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Clash Royale Best Boss Bandit Champion decks

- Vampire’s Fall 2 redeem codes and how to use them (June 2025)

- World Eternal Online promo codes and how to use them (September 2025)

- Best Arena 9 Decks in Clast Royale

- Mobile Legends January 2026 Leaks: Upcoming new skins, heroes, events and more

- Country star who vanished from the spotlight 25 years ago resurfaces with viral Jessie James Decker duet

- How to find the Roaming Oak Tree in Heartopia

- M7 Pass Event Guide: All you need to know

- Solo Leveling Season 3 release date and details: “It may continue or it may not. Personally, I really hope that it does.”

- Kingdoms of Desire turns the Three Kingdoms era into an idle RPG power fantasy, now globally available

2026-01-18 16:40