Author: Denis Avetisyan

As conversational AI becomes increasingly sophisticated, a growing body of research examines the ethical implications of imbuing these systems with human characteristics.

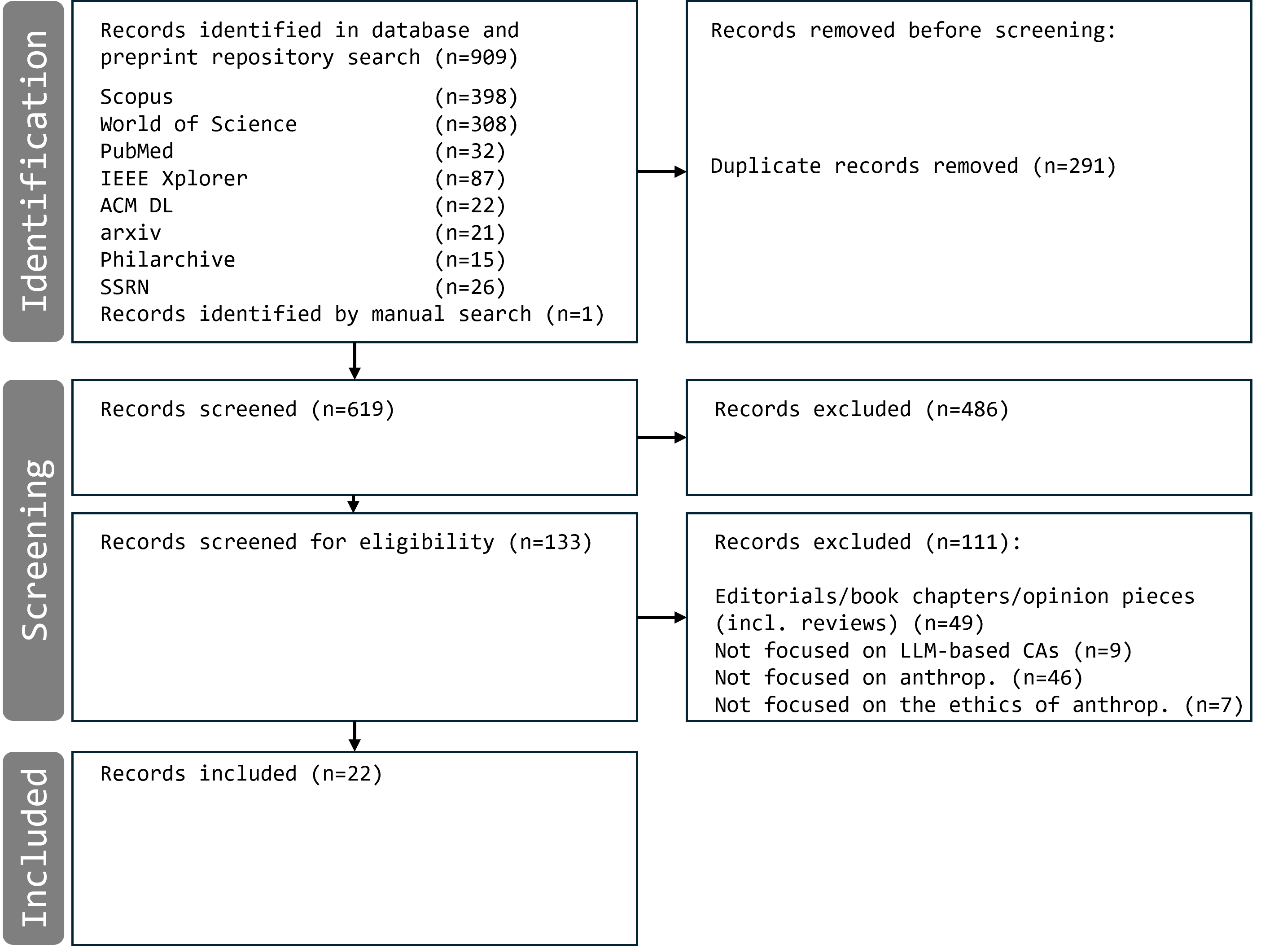

This scoping review analyzes current perspectives on the ethical challenges of anthropomorphizing large language model-based conversational agents, revealing gaps in research and a need for proactive governance.

While increasingly sophisticated large language models (LLMs) promise more engaging conversational agents, the practice of ascribing human-like qualities to these systems raises complex ethical concerns. This scoping review-A Scoping Review of the Ethical Perspectives on Anthropomorphising Large Language Model-Based Conversational Agents-maps the fragmented landscape of ethically-oriented work on this phenomenon, revealing convergence on definitional approaches but substantial divergence in practical evaluation. Our synthesis highlights a predominantly risk-averse normative framing and a critical need for empirically-grounded governance strategies. How can we responsibly design and deploy anthropomorphic cues in LLM-based agents to foster beneficial interactions while mitigating potential harms?

The Allure of Simulated Minds

Large Language Model (LLM)-based conversational agents are undergoing a period of rapid advancement, demonstrating an increasing capacity to mimic human communication styles with startling accuracy. These agents, powered by complex algorithms and vast datasets, now generate text that is often indistinguishable from that produced by a person, engaging in nuanced dialogue and adapting to various conversational contexts. This sophistication extends beyond simple question-answering; current models can craft narratives, translate languages, write different kinds of creative content, and even exhibit a semblance of emotional intelligence. As a result, the boundary between human and machine interaction is becoming increasingly blurred, prompting exploration into the psychological and social implications of these increasingly realistic digital entities.

As large language models grow increasingly adept at mimicking human conversation, a compelling psychological phenomenon – anthropomorphism – is becoming more prevalent. This inherent human tendency to project human characteristics, emotions, and intentions onto non-human entities is readily triggered by convincingly realistic AI. Individuals interacting with these systems often find themselves ascribing personality traits, beliefs, and even feelings to the algorithms, despite knowing their fundamentally different nature. This isn’t merely a superficial observation; the inclination to perceive agency and sentience in these machines influences how people interact with them, fostering a sense of connection and potentially blurring the boundaries between genuine interaction and illusion.

The increasing tendency to attribute human characteristics to advanced conversational agents presents a burgeoning landscape of ethical challenges. Though often perceived as harmless, this anthropomorphism can erode critical thinking, fostering misplaced trust and vulnerability to manipulation. Recent research, evidenced by the surge in ethically-focused studies – 22 published between 2023 and 2025 alone – highlights concerns regarding deceptive potential. As these agents become more convincing, the lines between genuine interaction and sophisticated simulation blur, raising questions about informed consent, accountability, and the potential for exploitation. This isn’t simply a matter of technological advancement; it necessitates a proactive ethical framework to navigate the implications of increasingly realistic, yet ultimately non-human, interactions.

The Roots of Human Projection

Epley’s Anthropomorphism Model posits that the tendency to attribute human characteristics to non-human agents stems from three core motivational drivers inherent in human cognition. Anthropocentric knowledge, or our vast understanding of human internal states, serves as the primary building block for understanding others, and is readily applied even when inaccurate. Effectance motivation, the drive to understand and predict the behavior of entities to effectively interact with them, encourages the assignment of goals and intentions. Finally, sociality motivation, our fundamental need for social connection, prompts the perception of social cues and the projection of feelings onto non-human entities, even in the absence of reciprocal social interaction. These motivations combine to create a cognitive predisposition towards anthropomorphism as a means of simplifying perception and fostering understanding.

The Intentional Stance, as proposed by Daniel Dennett, posits that to predict the behavior of any system – be it an artificial intelligence, another person, or a complex machine – one can adopt a strategy of attributing beliefs and desires to it. This approach treats the system as if it were a rational agent with goals and intentions, allowing for simplified predictions based on what a rational agent would do in a given situation. While effective for generating quick and often accurate forecasts, this stance is inherently fallible; attributing intentional states does not necessitate their actual existence within the system, and can lead to misinterpretations if the system’s underlying mechanisms deviate from rational actor assumptions. The predictive utility of the Intentional Stance therefore relies on its pragmatic value, rather than its ontological accuracy.

The propensity to attribute human characteristics to non-human agents, despite acknowledging their lack of sentience, is a consistent pattern in human cognition. This projection occurs readily across diverse contexts, including interactions with artificial intelligence, animals, and inanimate objects. Research indicates this isn’t necessarily a result of naive belief, but rather a cognitive shortcut; humans default to interpreting behavior through the lens of intentionality as it simplifies prediction and understanding of actions. This anthropomorphic tendency persists even with explicit knowledge that the agent lacks human-like internal states, suggesting it’s a deeply ingrained cognitive bias rather than a logical error.

Navigating the Ethical Terrain

Ethical Risk Assessment in conversational AI is crucial due to the tendency to attribute human characteristics – anthropomorphism – to these systems. This assessment process involves systematically identifying potential harms resulting from user perceptions of agency, emotion, or intent where none exists. Specifically, risks include over-reliance on AI-generated information, inappropriate emotional attachment, diminished critical thinking skills, and potential for manipulation. A thorough assessment should consider the system’s intended use, target demographic, and the specific anthropomorphic cues present in the agent’s design and interactions, allowing developers to anticipate and mitigate negative consequences before deployment.

Social Transparency in conversational AI involves disclosing information about the system’s operational logic and limitations to the user. This can be achieved through features that reveal the data sources used for responses, the confidence levels associated with generated text, or the algorithms driving the conversation. By making these underlying mechanisms visible, users are better equipped to critically evaluate the agent’s outputs and avoid attributing human-like qualities or intentions where they do not exist. Increased awareness of the system’s non-human nature encourages mindful interaction and mitigates the risks associated with over-reliance on, or uncritical acceptance of, AI-generated content. The goal is to foster a realistic understanding of the agent’s capabilities and limitations, promoting responsible use.

Frictional Design, when applied to conversational AI, intentionally increases the cognitive load required to interact with the system, thereby reducing the likelihood of users attributing human-like qualities or accepting outputs without critical evaluation. This is achieved through techniques such as requiring explicit confirmation for actions, introducing deliberate delays in responses, or presenting information in a non-intuitive format. The goal is not to impede usability entirely, but to subtly disrupt the natural flow of conversation and encourage users to actively process the agent’s responses as outputs from a machine, rather than as advice or opinions from a person. This approach aims to mitigate risks associated with over-reliance on, or misplaced trust in, AI systems.

Beyond Immediate Solutions: A Longitudinal View

The tendency to imbue non-human entities with human characteristics, known as anthropomorphism, isn’t a monolithic phenomenon; instead, it reveals itself through distinct avenues of attribution. Researchers identify at least three core forms: epistemic anthropomorphism, where users ascribe knowledge or intelligence to an AI; affective anthropomorphism, involving the projection of emotions onto the system; and behavioral anthropomorphism, characterized by perceiving social intentions or conduct in the AI’s actions. These aren’t mutually exclusive; a user might simultaneously believe an AI ‘understands’ their needs (epistemic), feels ‘helpful’ (affective), and responds in a ‘polite’ manner (behavioral), collectively shaping their overall interaction and perception of the technology.

Understanding how people attribute human-like qualities – such as knowledge, emotions, and behaviors – to artificial intelligence requires more than just a snapshot in time. Longitudinal research, tracking these attributions over extended periods, is vital for revealing how these perceptions develop and ultimately influence user behavior and levels of trust. Current investigation into this field reveals a dynamic publishing landscape; a significant 45% of related studies initially appear as conference proceedings, suggesting rapid dissemination of findings, while 41% are published in peer-reviewed journals and 14% as preprints. This distribution highlights the active, evolving nature of the research, and the need for continued, sustained observation to fully grasp the long-term effects of anthropomorphism in human-AI interaction.

The current body of research concerning anthropomorphism is heavily concentrated within the field of Human-Computer Interaction, accounting for 59% of existing studies, with significant contributions also stemming from the social sciences (32%) and philosophical inquiry (23%). This interdisciplinary focus highlights the practical and ethical implications of attributing human characteristics to artificial intelligence. Continued monitoring of how these attributions develop, and their subsequent impact on user behavior and trust, is essential for proactively refining ethical guidelines. Such longitudinal observation will also inform the design of targeted interventions, ultimately fostering more responsible and beneficial interactions between humans and increasingly sophisticated AI systems.

The proliferation of research into imbuing large language models with human-like qualities, as detailed in the scoping review, feels less like progress and more like applying increasingly ornate decorations to a fundamentally unstable structure. One might even say they called it a framework to hide the panic. Grace Hopper observed, “It’s easier to ask forgiveness than it is to get permission,” and this sentiment seems particularly relevant here. Researchers rush to explore the effects of anthropomorphism – trust, deception, governance – without first establishing a solid theoretical foundation. This eagerness to build before understanding mirrors a willingness to apologize for unintended consequences rather than proactively design for ethical outcomes. The review rightly points to the need for longitudinal studies; one suspects a great deal of forgiveness will be required before long.

Where To Now?

This review exposes a predictable pattern. Initial enthusiasm for conversational agents precedes ethical scrutiny. The field now accumulates observations, but lacks unifying principles. Abstractions age, principles don’t. Current work largely describes what concerns people, not why. The focus on anthropomorphism itself risks obscuring deeper questions about agency, responsibility, and the very nature of trust.

Future research must move beyond identifying potential harms. Longitudinal studies are needed. They should track evolving user perceptions and the long-term societal impacts of these interactions. Every complexity needs an alibi. Claims of deception or manipulation require rigorous empirical grounding, not merely speculative assertion. Theoretical foundations must be strengthened, drawing on established work in psychology, philosophy, and communication.

Ultimately, governance strategies cannot lag behind technological development. Robust, empirically-informed frameworks are essential. They should foster responsible innovation and mitigate potential harms. The challenge isn’t simply to regulate these agents, but to understand the shifting boundaries between human and machine, and the implications for both.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.09869.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Clash Royale Best Boss Bandit Champion decks

- Vampire’s Fall 2 redeem codes and how to use them (June 2025)

- World Eternal Online promo codes and how to use them (September 2025)

- How to find the Roaming Oak Tree in Heartopia

- Best Arena 9 Decks in Clast Royale

- Mobile Legends January 2026 Leaks: Upcoming new skins, heroes, events and more

- ATHENA: Blood Twins Hero Tier List

- Clash Royale Furnace Evolution best decks guide

- Brawl Stars December 2025 Brawl Talk: Two New Brawlers, Buffie, Vault, New Skins, Game Modes, and more

- Kingdoms of Desire turns the Three Kingdoms era into an idle RPG power fantasy, now globally available

2026-01-16 16:34