Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new analysis reveals that generating understandable explanations for machine learning decisions – particularly using counterfactual and semi-factual methods – can be computationally intractable.

The paper demonstrates that computing counterfactual and semi-factual explanations is often NP-hard, even for simple models, and provides insights into the limitations of current XAI techniques.

Despite the increasing demand for interpretable machine learning, providing clear explanations remains a significant challenge. This is the focus of ‘On the Hardness of Computing Counterfactual and Semifactual Explanations in XAI’, which analyzes the computational complexity of generating commonly used explanation types. Our work demonstrates that constructing even simple counterfactual or semi-factual explanations is often NP-hard and, crucially, difficult to approximate efficiently. Given these fundamental limitations, what algorithmic innovations or theoretical relaxations are needed to make explainable AI truly scalable and practical?

The Illusion of Explanation: A Computational Bottleneck

Despite achieving remarkable predictive accuracy, many contemporary machine learning models operate as ‘black boxes’, offering little insight into why a particular prediction was made. This lack of transparency isn’t simply a matter of inconvenience; it represents a fundamental challenge to deploying these systems in critical applications. While a model might correctly diagnose a disease or assess a loan risk, the inability to articulate the reasoning behind that decision hinders trust and accountability. The complexity of these models – often involving millions or even billions of parameters – obscures the relationship between input features and output predictions, making it difficult to identify the key factors driving a given outcome and potentially masking biases or spurious correlations. Consequently, even highly accurate predictions can be met with skepticism if the underlying rationale remains opaque, limiting their practical utility and raising ethical concerns.

The process of illuminating a machine learning model’s reasoning isn’t trivial; in fact, generating explanations, especially for those models boasting intricate architectures like deep neural networks, demands substantial computational resources. This isn’t merely a matter of running the model forward; it requires repeatedly perturbing inputs, re-evaluating the model, and analyzing the resulting changes to determine which features most influenced the prediction. Each iteration can be extraordinarily time-consuming, scaling poorly with model size and dataset complexity. Consequently, obtaining even a single explanation can require hours or even days of processing, creating a significant bottleneck that hinders the practical deployment of explainable AI, particularly in real-time applications or when dealing with massive datasets. The inherent difficulty lies in the exponential search space for minimal changes that meaningfully alter the model’s output, effectively turning explanation generation into a computationally intractable problem.

The lack of readily available explanations for machine learning predictions presents a significant impediment to deployment in high-stakes fields like healthcare and finance. Without understanding why a model arrives at a particular conclusion, professionals are understandably hesitant to rely on it for critical decision-making. In medical diagnoses, for example, a physician needs to evaluate the reasoning behind a suggested treatment, not simply accept the recommendation as a “black box” output. Similarly, in financial risk assessment, regulators and institutions require transparency to ensure fairness, prevent bias, and maintain market stability. This opacity erodes trust, hinders accountability, and ultimately slows the adoption of potentially beneficial artificial intelligence solutions where interpretability is paramount.

Determining why a machine learning model made a specific prediction often requires identifying the smallest possible alterations to the input that would change the outcome – a process akin to reverse-engineering a complex decision. This search for ‘minimal sufficient cause’ is computationally demanding because the input space for many real-world problems is vast and high-dimensional. The model’s internal workings, particularly in deep neural networks, are non-linear and opaque, meaning even seemingly small input changes can trigger cascading effects. Consequently, pinpointing the precise features driving a prediction demands exploring a combinatorial explosion of possibilities, effectively creating a computational bottleneck that hinders the generation of timely and trustworthy explanations. The difficulty isn’t simply finding an explanation, but finding the most concise and therefore most meaningful one.

Beyond Faithful Explanations: Sufficient Reasons and Counterfactual Insights

Semi-factual explanations function by identifying input feature perturbations that have no impact on the model’s prediction. This approach differs from traditional feature importance methods by focusing on sufficient features rather than those simply correlated with the outcome. The core principle involves systematically altering input features while observing whether the prediction remains constant; features that do not change the prediction are deemed non-critical for that specific instance. By identifying these stable features, semi-factual explanations effectively highlight the minimal set of features that are necessary to maintain the model’s output, offering a pragmatic and interpretable view of the model’s reliance on specific inputs.

Minimum Sufficient Reasons (MSR) is a principle applied in explainable AI to identify the smallest subset of input features that are sufficient to maintain the model’s prediction. This approach contrasts with methods that highlight all influential features; instead, MSR seeks to pinpoint only those features absolutely necessary for the outcome. The underlying logic is that by minimizing the number of features highlighted, the explanation becomes more concise and interpretable, focusing on the core drivers of the model’s decision. Computationally, MSR often involves iteratively removing features and assessing the impact on the prediction until the smallest set is identified that preserves the original outcome with a high degree of confidence.

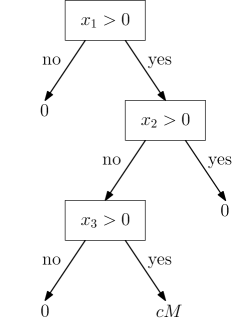

Counterfactual explanations function by identifying the smallest alterations to an input feature set that would result in a different model prediction. This approach generates “what if” scenarios, demonstrating how specific input changes influence the outcome. The process involves searching for the minimal feature perturbations – additions, subtractions, or modifications – needed to flip the prediction to a desired alternative. Unlike explanations focusing on reasons for a prediction, counterfactuals highlight the conditions required to change the prediction, providing actionable insights for influencing model behavior and understanding decision boundaries.

Semi-factual and counterfactual explanation techniques, while offering valuable insights into model behavior, do not necessarily replicate the precise internal reasoning of the model itself. These methods prioritize providing actionable explanations – identifying minimal input changes that maintain or alter predictions – over strict fidelity to the model’s complex decision-making process. Consequently, the explanations generated represent approximations of the model’s rationale, focusing on sufficient conditions for a given outcome rather than a complete and exhaustive depiction of the model’s internal logic. This pragmatic approach allows users to understand what changes influence predictions, even if the why remains partially obscured, facilitating trust and informed interaction with the model.

The Inherent Limits of Explanation: NP-Hardness and Computational Complexity

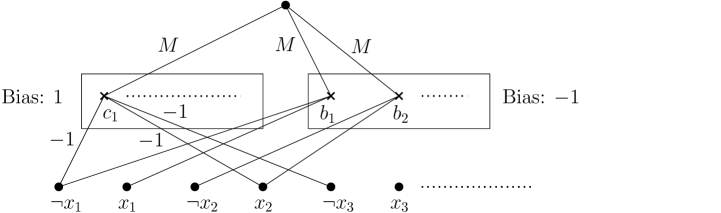

The computational complexity of finding optimal counterfactual explanations has been formally established as NP-hard, indicating a problem class for which no polynomial-time algorithm is known to exist. This classification places counterfactual explanation search on par with well-known intractable problems such as the Boolean satisfiability problem (3-SAT). An NP-hard problem’s computational demands grow exponentially with the input size, specifically the number of features in the model being explained. Consequently, as the dimensionality of the feature space increases, the time required to find an optimal counterfactual explanation rises dramatically, making exhaustive search impractical for many real-world machine learning models and datasets.

The exponential growth in computational time associated with increasing feature dimensionality presents a significant obstacle to generating optimal counterfactual explanations. As the number of features (variables) in a model increases, the search space for identifying minimal changes to an input that alter the model’s prediction grows at a rate that quickly exceeds the capacity of available computing resources. This characteristic-specifically, a time complexity that scales exponentially with the number of features-means that even moderately complex datasets can render exact solution methods computationally infeasible within practical timeframes, necessitating the use of approximation algorithms or heuristic approaches for real-world applications.

Computational Complexity Analysis utilizes established techniques from theoretical computer science to rigorously evaluate the scalability of explanation methods. This involves determining the resources – typically time and space – required by an algorithm as the input size grows. Analysis is performed by characterizing the algorithmic complexity using Big O notation, and assessing performance across diverse machine learning models. Specifically, this framework has been applied to models such as Decision Trees, where explanation complexity is related to tree depth and branching factor; ReLU Networks, where complexity is linked to the number of layers and neurons; and k-Nearest Neighbors, where complexity is determined by the data dimensionality and search algorithms employed. This formal assessment allows for comparison of different explanation techniques and identification of bottlenecks that limit their practical application to large datasets.

The research establishes the NP-hardness of computing robust and optimal counterfactual explanations for various machine learning models. This is formally demonstrated by proving that no polynomial-time algorithm can achieve a 2p(n) approximation for the WACHTER-CFE problem, where p(n) represents a polynomial function of the number of features. This result indicates a fundamental computational limitation; as the dimensionality of the feature space increases, the time required to find even approximate solutions grows exponentially, precluding the use of exact methods for practical, high-dimensional datasets.

Towards Pragmatic Explanation: Robustness, Plausibility, and Acceptance of Imperfection

The reliability of explanations generated by artificial intelligence systems is often challenged by the inherent noise present in real-world data. To address this, research increasingly focuses on robust counterfactuals – explanations that don’t drastically change even when the input data is slightly altered. These explanations identify minimal changes to an input that would lead to a different outcome, but crucially, a robust counterfactual remains a valid explanation even if those changes are not perfectly precise. This is achieved by considering a range of plausible perturbations, ensuring the explanation isn’t overly sensitive to minor variations in the data. By prioritizing stability under perturbation, these explanations provide more trustworthy insights, particularly in dynamic or uncertain environments where perfect data is rarely available, and offer a significant improvement over explanations that are brittle and easily invalidated by noise.

The utility of an explanation hinges not only on its accuracy, but also on its plausibility – how well it aligns with established knowledge of the world. Counterfactual explanations, which detail what changes would lead to a different outcome, are significantly more valuable when they respect real-world constraints and feasibility. An explanation suggesting a user earn a Ph.D. to qualify for a loan, while technically a solution, lacks plausibility and thus, actionability. Prioritizing plausible counterfactuals ensures explanations are not merely logically correct, but also readily understandable and implementable by those seeking insight, ultimately fostering trust and enabling effective decision-making.

The pursuit of flawlessly accurate explanations in artificial intelligence often clashes with real-world constraints and computational limits. Instead of striving for an unattainable ideal, current research advocates for a pragmatic approach – focusing on explanations that are ‘good enough’ for practical application. This involves accepting a degree of approximation while prioritizing robustness and plausibility, ensuring explanations remain reliable even with noisy data and adhere to real-world constraints. By acknowledging that perfect explanations are likely impossible, developers can concentrate on building AI systems that offer trustworthy and useful insights, even if those insights aren’t absolute, ultimately fostering greater confidence and facilitating effective decision-making in complex scenarios.

The pursuit of perfectly explaining complex artificial intelligence decisions faces a fundamental barrier: computational intractability. Research demonstrates that, for certain explanation problems – specifically, the WACHTER-CFE problem – no algorithm can deliver a solution with a 2p(n) approximation within a reasonable timeframe, regardless of computing power. This isn’t a limitation of current technology, but an inherent property of the problem itself. Consequently, a pragmatic approach to explainable AI focuses on designing methods that are ‘fit for purpose’ – prioritizing valuable insights over absolute precision. Instead of striving for unattainable perfection, developers can build explanation techniques that provide useful, actionable information within acceptable computational limits, acknowledging that a good explanation doesn’t necessitate a complete one.

The pursuit of explainable artificial intelligence frequently encounters inherent computational limitations. This paper demonstrates that generating even basic counterfactual explanations can quickly become intractable, falling into the realm of NP-hard problems. Such complexity isn’t a flaw, but an expected consequence of attempting to distill nuanced model behavior into human-understandable terms. As Linus Torvalds observed, “Talk is cheap. Show me the code.” The elegance of a solution isn’t measured by its conceptual simplicity, but by its practical feasibility. This research echoes that sentiment, revealing the stark reality that many XAI methods, while theoretically appealing, lack the computational grounding necessary for real-world deployment. The focus, therefore, must shift toward approximation algorithms and pragmatic trade-offs between explanation fidelity and computational cost.

Where Do We Go From Here?

The demonstration of inherent computational difficulty in generating even basic explanations should give pause. It was, perhaps, optimistic to believe that post-hoc interpretability would be easy. They called it a framework to hide the panic, but a problem proven NP-hard doesn’t yield to prettier interfaces. The field now faces a necessary reckoning: not every model needs an explanation, and not every explanation needs to be perfect. A relentless pursuit of completeness may simply be a distraction from more pragmatic goals.

Future work will likely center on identifying tractable subclasses of models or explanation types. Approximation algorithms, while offering a compromise, demand careful consideration of their fidelity – a near-miss explanation is often worse than none at all. More fruitful avenues may lie in preventative interpretability – designing models that are inherently understandable, rather than attempting to dissect opaque black boxes.

Ultimately, the enduring challenge is not merely to generate explanations, but to determine when an explanation is genuinely useful. Simplicity, it turns out, isn’t just a virtue, it’s a constraint. The elegance of a solution is often proportional to what it leaves out. A mature field will learn to accept that limitation.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.09455.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Clash Royale Best Boss Bandit Champion decks

- Vampire’s Fall 2 redeem codes and how to use them (June 2025)

- World Eternal Online promo codes and how to use them (September 2025)

- How to find the Roaming Oak Tree in Heartopia

- Best Arena 9 Decks in Clast Royale

- Mobile Legends January 2026 Leaks: Upcoming new skins, heroes, events and more

- ATHENA: Blood Twins Hero Tier List

- Clash Royale Furnace Evolution best decks guide

- Brawl Stars December 2025 Brawl Talk: Two New Brawlers, Buffie, Vault, New Skins, Game Modes, and more

- What If Spider-Man Was a Pirate?

2026-01-16 05:38