Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new framework streamlines path planning for mobile robots operating in complex three-dimensional spaces filled with obstacles.

This review details a unified approach to constructing smooth navigation functions for spherical robots and other systems, ensuring safe and efficient motion in 3D environments.

Effective motion planning for robots navigating complex 3-D spaces remains challenging due to the computational burden of ensuring both safety and efficiency. This technical report, ‘Feedback-Based Mobile Robot Navigation in 3-D Environments Using Artificial Potential Functions’, addresses this by presenting a novel polynomial framework for constructing smooth navigation functions in environments populated with spherical and cylindrical obstacles. The core finding is a set of admissibility conditions guaranteeing a unique, globally attractive minimum at the target location, thereby avoiding problematic local minima even with intersecting obstacles. Will this approach pave the way for more robust and adaptable autonomous navigation systems in increasingly cluttered real-world scenarios?

The Idealization of Movement: Bridging the Gap Between Theory and Reality

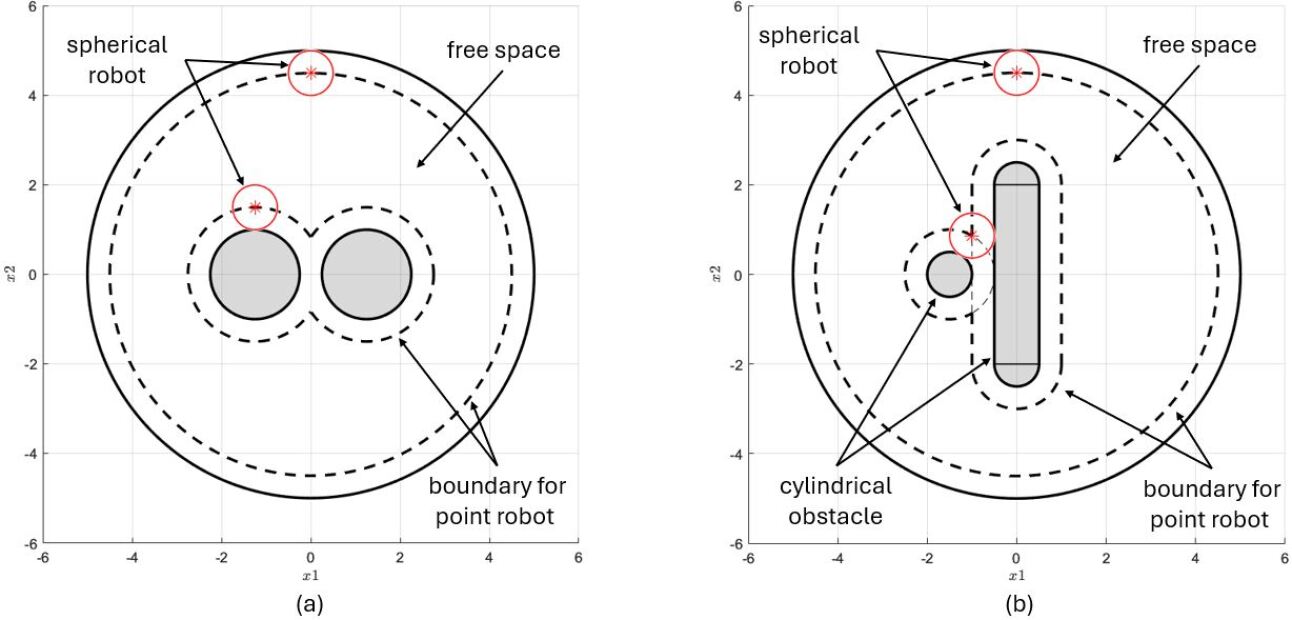

Conventional approaches to robot path planning frequently treat the robot as a simple point, a mathematical idealization that disregards crucial physical limitations. This simplification, while computationally convenient, introduces inaccuracies when applied to real-world scenarios. A robot’s actual size, shape, and the dynamics of its movement – including turning radius, acceleration limits, and joint constraints – are all ignored by these methods. Consequently, paths generated under this assumption may be physically impossible for the robot to execute, potentially leading to collisions or instability. More sophisticated algorithms are therefore needed to account for these constraints, ensuring that planned trajectories are not only collision-free but also dynamically feasible, allowing the robot to navigate complex environments safely and effectively.

Successfully navigating real-world scenarios demands more than simple route calculation for robots; it requires algorithms capable of handling unpredictable obstacles and dynamic environments. Unlike controlled factory settings, outdoor or domestic spaces present irregular shapes, moving objects – such as people and pets – and often incomplete or noisy sensor data. Robust path planning algorithms must therefore incorporate techniques like probabilistic roadmaps or rapidly-exploring random trees, which allow the robot to efficiently search for feasible paths while accounting for uncertainty. Furthermore, these algorithms need to balance computational speed with safety, ensuring the robot can react quickly to avoid collisions while still reaching its destination efficiently. The development of such resilient navigation systems is crucial for the widespread adoption of robots in diverse, unstructured environments, moving beyond the limitations of pre-programmed routes and controlled settings.

Quantifying the Obstacle: A Mathematical Representation of Space

Accurate path planning for autonomous robots is fundamentally dependent on the creation of a quantifiable representation of the environment’s obstacles. This representation must define obstacle locations, dimensions, and shapes in a format suitable for algorithmic processing. Without a precise mathematical model, algorithms cannot reliably determine collision-free trajectories. Commonly, this involves defining obstacles using geometric primitives such as points, lines, polygons, spheres, or cylinders, each described by numerical parameters. The fidelity of this representation directly impacts the robot’s ability to navigate complex environments and avoid collisions; increased precision generally demands greater computational resources for path planning calculations.

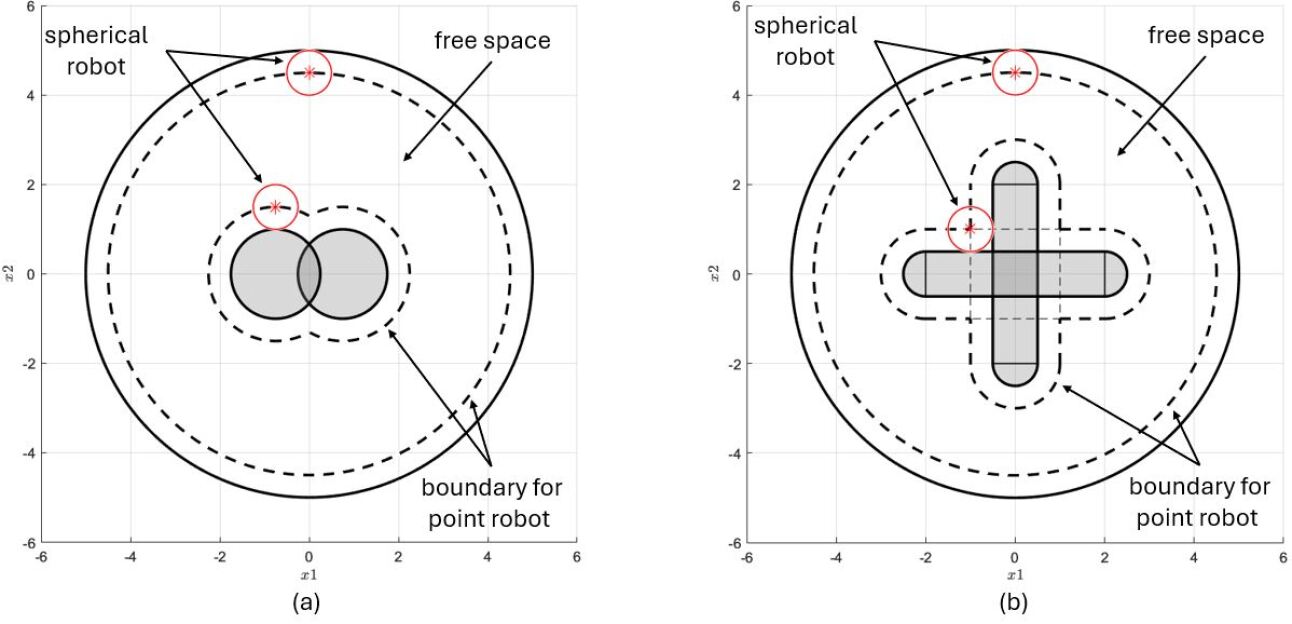

The Rvachev function provides a method for representing the free space surrounding obstacles by calculating a continuous distance field. This function, defined as R(x,y) = \min_{i} \{ ||(x,y) - c_i|| - r_i \} , where c_i represents the center and r_i the radius of the ith obstacle, effectively merges overlapping obstacle boundaries. A positive value of R(x,y) indicates a point is in free space, while a non-positive value signifies the point is within an obstacle. This continuous representation simplifies path planning algorithms by allowing them to treat the environment as a smooth function rather than a collection of discrete boundaries, and facilitates efficient collision detection.

Spherical and cylindrical obstacles represent simplified geometric primitives frequently employed in robot environment modeling due to their computational efficiency. A sphere is defined by its center and radius, requiring three parameters, while a cylinder requires three parameters to define its base circle and one for its height. These shapes allow for collision detection calculations using relatively simple distance formulas; for example, the distance between a point and a sphere can be determined by calculating the Euclidean distance between the point and the sphere’s center, comparing it to the radius. Similarly, point-cylinder distance calculations involve assessing the distance to the cylinder’s axis and comparing it to the radius and half-height. The use of these simplified shapes trades off representational accuracy for reduced computational load, enabling real-time path planning and obstacle avoidance in dynamic environments.

The Scalar Potential: Guiding the Robot Through Configuration Space

A navigation function represents the robot’s configuration space as a scalar field, assigning a real value to each point representing the ‘cost’ to reach the goal. Lower values indicate proximity to a feasible path, while obstacles and invalid configurations are assigned higher values. This function serves as a generalized distance metric, enabling path planning by directing the robot to descend the potential field – effectively moving from high-value regions to low-value regions. The function must be continuous to ensure smooth robot trajectories and must define a unique global minimum at the goal location to guarantee convergence. By formulating the environment in this manner, complex geometric constraints can be translated into a differentiable potential, simplifying path planning algorithms and enabling the use of gradient-based optimization techniques.

Admissibility and polarity are critical characteristics of a navigation function to guarantee successful path planning. A navigation function is considered admissible if it attains a global minimum value of zero solely at the goal location; any other point in the configuration space must yield a positive value. Polarity dictates that the function’s value decreases monotonically as the robot approaches the goal, meaning the function value will never increase along a path towards the target. These properties ensure that the robot is consistently guided towards the goal without getting trapped in local minima, and that the gradient descent algorithm will converge to the desired target configuration, enabling safe navigation in the presence of obstacles.

The robot’s velocity is directly determined by the negative gradient of the navigation function; a steeper gradient indicates a higher velocity magnitude, directing movement towards decreasing potential. Path curvature is defined by the Hessian matrix of the navigation function, which represents the second partial derivatives of the potential field. Positive definite Hessians ensure locally convex paths, preventing oscillations and promoting smooth trajectories; the eigenvalues of the Hessian determine the principal curvatures at any given point along the path, influencing the robot’s turning radius and stability. \nabla f(x) represents the gradient, and \nabla^2 f(x) represents the Hessian of the navigation function f(x) .

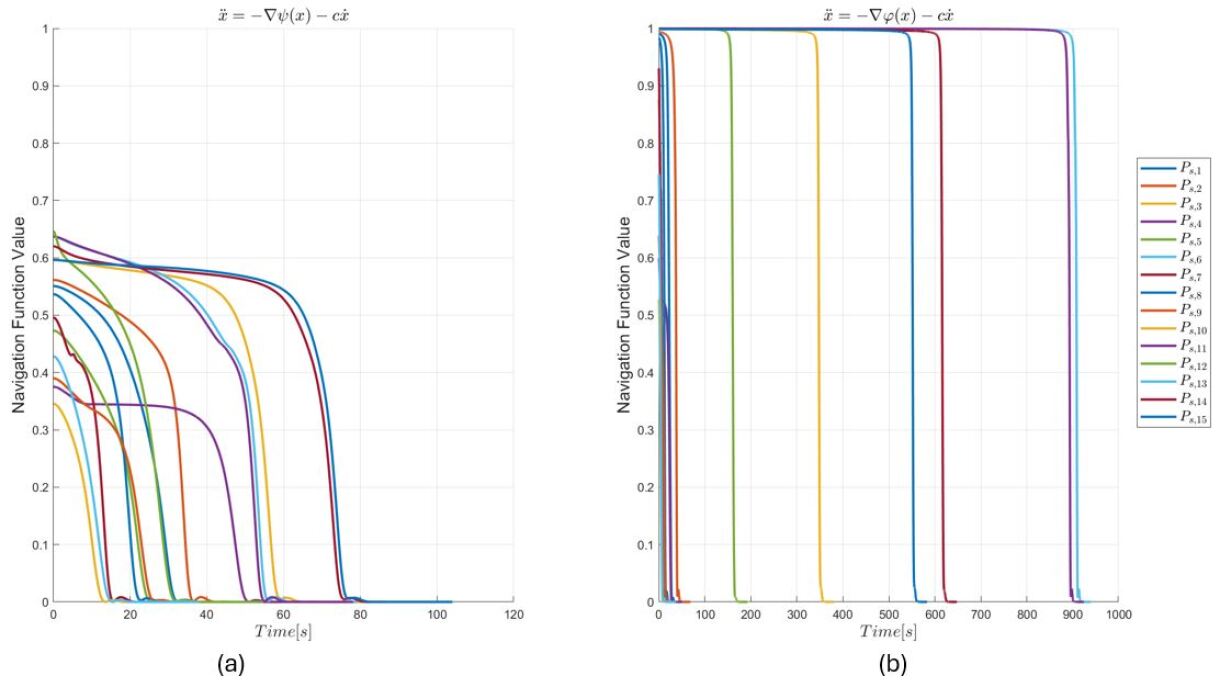

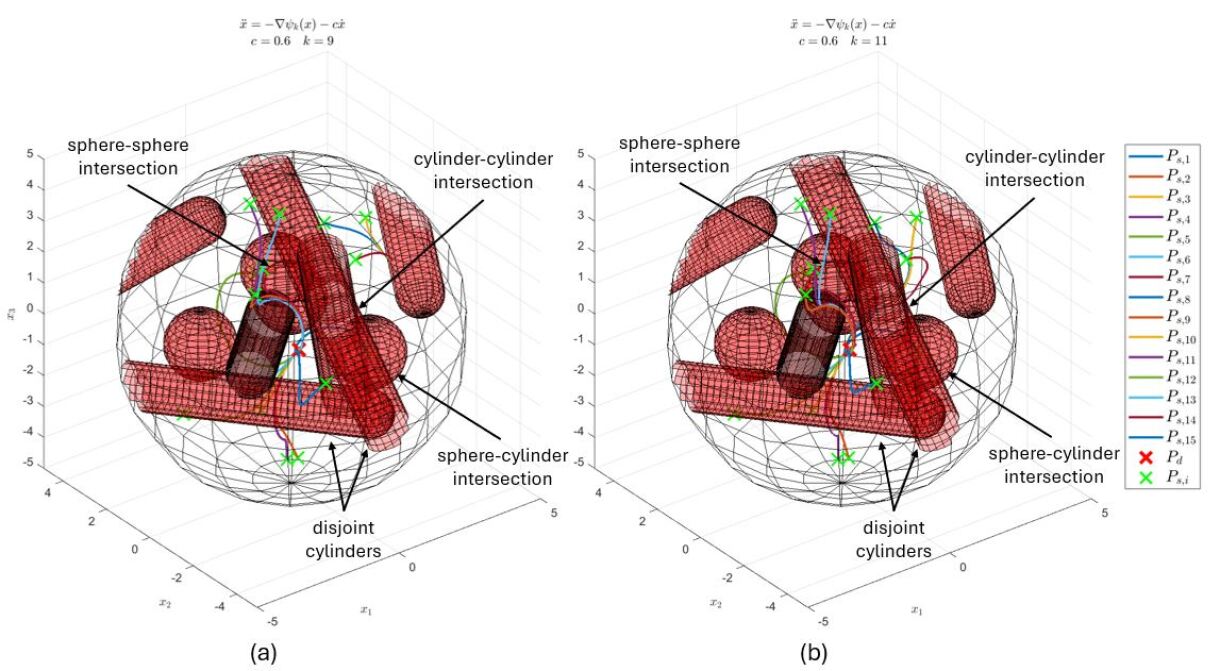

Demonstrating Robustness: Validation and Refinement Through Simulation

The performance of the developed navigation function underwent rigorous validation through detailed simulations mirroring real-world conditions. These virtual environments weren’t simply open spaces; they incorporated complex geometric structures, specifically truss obstacles, designed to challenge the algorithm’s path-planning capabilities. By subjecting the function to these demanding scenarios, researchers could assess its ability to generate feasible and efficient routes without collisions. This simulation-based approach offered a controlled and repeatable means of evaluating performance, allowing for iterative refinement and optimization before any potential implementation in physical robotic systems. The fidelity of the simulated environment was paramount, ensuring that the results accurately reflected how the function would behave in a tangible setting.

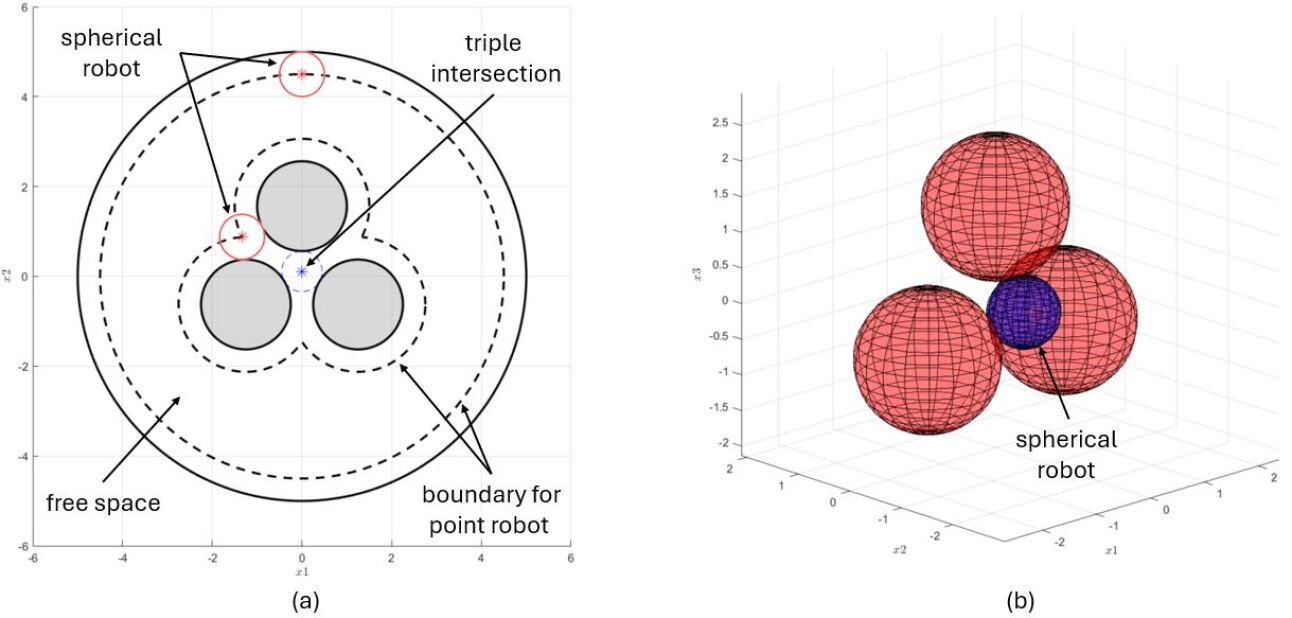

Rigorous testing of a navigation algorithm demands exposure to exceedingly complex scenarios, and triple intersections of obstacles represent a particularly telling challenge. These configurations, where pathways are narrowly constrained by multiple obstructions converging at a single point, effectively expose weaknesses in an algorithm’s ability to find globally optimal routes. Unlike simpler obstacles that allow for straightforward detours, triple intersections force the navigation function to delicately balance competing avoidance pressures, precluding reliance on localized, reactive behaviors. Successfully navigating such intricate environments demonstrates the algorithm’s capacity to plan effectively, avoid becoming trapped in local minima, and maintain a robust solution even under significant spatial constraints-a crucial benchmark for real-world applicability where unpredictable obstacle arrangements are commonplace.

The performance of the navigation function is critically dependent on the tuning parameter, K, which effectively sculpts its overall shape and dictates its susceptibility to becoming trapped in local minima – points where the function appears optimal but prevents reaching the true goal. Research indicates that a precisely calibrated K value of 40 proves instrumental in eliminating these problematic local minima within simulated environments. This optimization allows the navigation function to consistently identify and pursue the most efficient path, avoiding deceptive detours and ensuring reliable trajectory planning even in complex scenarios. The elimination of local minima is a key feature, allowing for robust pathfinding and a significantly increased probability of successful navigation.

Rigorous testing within simulated three-dimensional environments reveals the proposed navigation function achieves a perfect success rate when confronted with complex truss obstacles. Utilizing a carefully tuned parameter, K, set to a value of 40, the algorithm consistently identifies and executes optimal paths. This 100% success rate demonstrates the robustness of the method, signifying its capability to reliably guide a virtual agent through challenging spatial configurations. The elimination of navigational failures in these simulations suggests a high degree of adaptability and precision, paving the way for potential implementation in more complex real-world robotic applications and autonomous systems. This performance underscores the effectiveness of the proposed approach in addressing the critical need for dependable path planning in obstructed environments.

The presented work rigorously establishes a foundation for predictable robotic movement through mathematically defined potential fields. This approach mirrors a commitment to provable correctness, rather than empirical testing, as evidenced by the unified polynomial framework for navigation function construction. As Linus Torvalds aptly stated, “Talk is cheap. Show me the code.” This sentiment aligns perfectly with the paper’s emphasis on a formal, mathematically grounded solution for 3D motion planning, prioritizing demonstrable safety and efficiency over heuristic approaches. The resulting navigation functions, built upon a polynomial framework, are not simply working solutions; they are demonstrably correct within the defined workspace decomposition and obstacle representation.

What Lies Ahead?

The construction of provably safe navigation functions, even within a polynomial framework, remains a surprisingly subtle undertaking. This work achieves a commendable level of generality with spherical and cylindrical obstacles, yet the inherent limitations of artificial potential fields – local minima, oscillating behaviors – are merely mitigated, not eradicated. One suspects the true elegance lies not in increasingly sophisticated potential formulations, but in a fundamentally different approach to guaranteeing global admissibility. If a path feels like magic, one hasn’t revealed the invariant.

Future efforts should concentrate less on obstacle representation and more on workspace decomposition. The current paradigm implicitly assumes a static environment. A truly robust system will demand dynamic obstacle avoidance, requiring a reformulation of the potential function to account for predictive modeling and time-varying constraints. Consider, for instance, the challenge of navigating cluttered spaces populated by agents with non-holonomic constraints – a scenario where polynomial smoothness alone is insufficient.

Ultimately, the pursuit of autonomous navigation demands a shift in emphasis. The field fixates on generating paths; a more fruitful direction involves formally verifying properties of motion – properties such as collision avoidance, arrival at a goal state within a specified time, and energy efficiency. Only then can one claim true progress beyond empirical demonstration.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.09318.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Clash Royale Best Boss Bandit Champion decks

- Vampire’s Fall 2 redeem codes and how to use them (June 2025)

- World Eternal Online promo codes and how to use them (September 2025)

- Mobile Legends January 2026 Leaks: Upcoming new skins, heroes, events and more

- How to find the Roaming Oak Tree in Heartopia

- Best Arena 9 Decks in Clast Royale

- ATHENA: Blood Twins Hero Tier List

- Clash Royale Furnace Evolution best decks guide

- Brawl Stars December 2025 Brawl Talk: Two New Brawlers, Buffie, Vault, New Skins, Game Modes, and more

- Clash Royale Season 79 “Fire and Ice” January 2026 Update and Balance Changes

2026-01-15 16:13