Author: Denis Avetisyan

This review explores how deep neural networks are transforming the fields of reinforcement and imitation learning, enabling agents to learn complex behaviors from experience and demonstration.

A comprehensive overview of foundational algorithms including REINFORCE, Proximal Policy Optimization, and techniques for continuous action spaces within Markov Decision Processes.

Designing effective controllers for complex, sequential decision-making tasks remains a significant challenge in robotics and artificial intelligence. This document, ‘An Introduction to Deep Reinforcement and Imitation Learning’, provides a focused exploration of two promising learning-based approaches-Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) and Deep Imitation Learning (DIL)-that leverage deep neural networks to optimize agent behavior. By examining foundational algorithms like REINFORCE, Proximal Policy Optimization, and techniques such as Dataset Aggregation, this work prioritizes in-depth understanding of policy representation and value function approximation. How can these techniques be further refined to create truly autonomous and adaptable embodied agents?

Deconstructing Choice: The Foundations of Sequential Decision-Making

Consider the multitude of challenges faced daily – from navigating a city to managing financial investments, or even controlling a robotic system. These are not isolated events, but rather sequences of choices where current actions influence future possibilities. This principle of sequential decision-making underpins a vast array of real-world problems; an agent operates within an environment, taking actions, observing the resulting changes, and learning to optimize its behavior over time. The core characteristic is that each decision doesn’t exist in isolation, but builds upon previous ones, creating a dynamic interplay between action and consequence. Effectively addressing these problems necessitates a framework capable of modeling this temporal dependence and evaluating the long-term impact of each choice, a need that motivates the development of robust decision-making algorithms.

The Markov Decision Process, or MDP, furnishes a robust mathematical structure for dissecting problems involving sequences of choices. It formally defines an agent’s interaction with an environment through a quartet of core elements: states, representing the agent’s situation; actions, the choices available to the agent; rewards, quantifying the immediate benefit of an action; and transitions, detailing how actions alter the environment and move the agent between states. This framework allows for a precise formulation of complex challenges – from robotic navigation to game playing – as a search for an optimal policy, a strategy that maximizes cumulative reward over time. By explicitly modeling these components, the MDP provides a foundation for developing algorithms capable of learning and adapting to dynamic environments, offering a pathway to intelligent behavior in a wide array of applications. The elegance of the MDP lies in its ability to represent uncertainty and sequential dependencies, making it a cornerstone of modern reinforcement learning.

The core of any Markov Decision Process lies in two critical functions: the dynamics function and the reward function. The dynamics function, often represented as $P(s’|s,a)$, mathematically defines the probability of transitioning to a new state, $s’$, given a current state, $s$, and an action, $a$. Essentially, it encapsulates the environment’s response to an agent’s choices, modeling the inherent uncertainty or determinism of the world. Complementing this is the reward function, denoted as $R(s,a,s’)$, which assigns a numerical value representing the immediate benefit or cost associated with taking a specific action in a given state and transitioning to a new state. This function provides the agent with a signal, guiding it towards desirable outcomes and away from unfavorable ones, and ultimately shaping its long-term behavior within the environment. Together, these functions completely define the problem, allowing for the formulation of optimal decision-making strategies.

Directing the Agent: Unveiling Policy Gradient Methods

Unlike many reinforcement learning algorithms that rely on estimating a value function – which predicts the expected future reward for being in a given state or taking a specific action – Policy Gradient Methods directly optimize the agent’s policy. The policy defines the agent’s behavior, mapping states to actions, and is adjusted to maximize the expected cumulative reward, often denoted as $R$. This direct optimization bypasses the need for value function approximation, potentially leading to improved performance and stability in certain environments. By directly learning the optimal policy, the agent aims to select actions that yield the highest long-term reward without explicitly evaluating the worth of each state-action pair.

Policy gradient methods directly modify the agent’s policy parameters through a process of reinforcement learning. Observed returns, representing the cumulative reward received after taking an action in a given state, are used to adjust the probability of selecting that action in the future. A positive return increases the likelihood of repeating the action, while a negative return decreases it. This adjustment is typically implemented using gradient ascent, where the policy parameters are updated in the direction of increasing expected return. The magnitude of the update is determined by a learning rate and the magnitude of the observed return, effectively strengthening actions associated with favorable outcomes and weakening those leading to unfavorable ones.

The expected return, or the average cumulative reward anticipated from a given state and action, functions as the primary optimization target in policy gradient methods. Unlike value-based methods which infer an optimal policy from a value function, policy gradients directly maximize this expected return by adjusting policy parameters in the direction of actions yielding higher rewards. Empirical results demonstrate that utilizing the expected return as a direct optimization signal improves learning stability – reducing oscillation and divergence – and enhances sample efficiency by focusing learning on actions with demonstrably positive long-term outcomes, often requiring fewer interactions with the environment compared to methods reliant on value function approximation.

The REINFORCE algorithm utilizes Monte Carlo methods to estimate the expected return, or cumulative reward, by running complete episodes of interaction with the environment. This involves sampling trajectories – sequences of states, actions, and rewards – until the terminal state is reached. The total discounted reward obtained from each episode serves as an unbiased estimate of the value of following the policy that generated that trajectory. By averaging these returns across multiple episodes, REINFORCE calculates a policy gradient that indicates the direction of parameter adjustments needed to increase the probability of actions associated with higher cumulative rewards. The use of complete episodes, while computationally intensive, provides a low-variance estimate crucial for stable policy updates, particularly in environments with stochastic transitions or rewards.

Taming the Update: Stabilizing Learning with Proximal Policy Optimization

Policy gradient methods, while powerful, are susceptible to instability due to the potential for large policy updates. Each iteration of these methods adjusts the policy to increase expected reward; however, substantial alterations to the policy distribution can lead to a significant drop in performance. This occurs because the agent may begin exploiting previously unseen states or actions, or unlearn previously successful behaviors, before sufficient data can be gathered to correct the change. The magnitude of this performance degradation is directly related to the step size of the policy update; larger steps introduce more risk of destabilizing the learning process and require careful tuning of hyperparameters to maintain stable learning.

Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) is a policy gradient method designed to improve training stability by restricting the extent of policy updates in each iteration. This limitation is achieved through the use of a clipped surrogate objective function, which penalizes changes to the policy that deviate significantly from the previous policy. Empirical results demonstrate that PPO consistently converges to optimal or near-optimal policies across a range of benchmark environments, including those used for evaluating reinforcement learning algorithms, and exhibits improved sample efficiency compared to other policy gradient methods by maintaining a balance between exploration and exploitation.

Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) stabilizes learning by constraining policy updates using the $KL$ Divergence. This metric quantifies the difference between the probability distributions of the old and new policies; a larger $KL$ Divergence indicates a more substantial change. PPO incorporates this divergence as a penalty in the objective function, effectively limiting how far the new policy can deviate from the previous one during each update step. By controlling the magnitude of policy changes, PPO avoids drastic behavioral shifts that can lead to performance degradation, promoting more reliable and consistent learning.

Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) functions as an Actor-Critic method, employing two core components to enhance learning. The “actor” represents the policy, responsible for selecting actions based on the current state, while the “critic” evaluates the quality of those actions by estimating the state value function. This value function provides feedback to the actor, guiding policy updates and reducing variance in policy gradient estimates. By decoupling action selection from value assessment, PPO facilitates more efficient exploration and exploitation, leading to improved reward accumulation during training as demonstrated in empirical results. The critic’s value estimates are used to form a baseline against which the actor’s performance is measured, further stabilizing learning and promoting consistent improvement.

Beyond the Horizon: Limitations and Future Directions

Reinforcement learning agents frequently encounter difficulty when operating in partially observable environments, a common characteristic of real-world scenarios. Unlike simulations offering complete state information, many applications – such as robotics or autonomous driving – present agents with limited or noisy sensory inputs. This partial observability hinders the agent’s ability to accurately assess its current situation and, consequently, make optimal decisions. Traditional reinforcement learning algorithms, designed under the assumption of full observability, often fail to generalize effectively when faced with this uncertainty, leading to suboptimal performance and instability. The agent struggles to differentiate between states that appear similar based on limited observations, impacting its ability to learn a reliable policy and achieve its goals. Addressing this limitation is crucial for deploying intelligent agents in complex, real-world environments where complete information is rarely, if ever, available.

The challenge of partial observability necessitates a shift towards algorithms capable of sophisticated reasoning under uncertainty. Rather than assuming complete knowledge of the environment’s state, these approaches focus on maintaining a belief state – a probability distribution over all possible states given the history of observations. This belief state acts as the agent’s internal representation of its surroundings, continually updated as new information becomes available through sensors or interactions. Effectively managing this belief state requires integrating techniques from Bayesian filtering, Kalman filtering, or particle filtering with reinforcement learning frameworks, allowing the agent to make informed decisions even with incomplete or noisy data. The success of such algorithms hinges on their ability to accurately estimate and propagate uncertainty, enabling robust performance in complex and unpredictable environments, and ultimately paving the way for more adaptable and reliable intelligent systems.

A promising avenue for advancing reinforcement learning lies in the synergistic combination of policy gradient methods with the principles of probabilistic reasoning and state estimation. Current policy gradients excel at learning directly from experience, but often falter when faced with incomplete information; integrating techniques like Bayesian filtering or Kalman smoothing could allow agents to maintain a robust belief state – a probability distribution over possible environment states – even when observations are noisy or partial. This belief state can then inform the policy gradient updates, enabling more informed decision-making under uncertainty. Such hybrid approaches aim to leverage the strengths of both paradigms: the efficient learning of policy gradients and the robust state representation afforded by probabilistic methods, potentially unlocking more adaptable and reliable intelligent agents capable of operating effectively in complex, real-world scenarios.

The successful navigation of complex, real-world scenarios demands intelligent agents capable of functioning despite incomplete and often unreliable data. Current limitations in reinforcement learning, particularly regarding partial observability, hinder the deployment of such agents in practical applications. However, ongoing research focused on robust algorithms that can effectively reason under uncertainty promises to unlock these capabilities. A critical component of this progress lies in stabilizing the training process; implementation of KL divergence-based early stopping offers a compelling solution by preventing excessive policy drift, ensuring the agent learns a consistently effective strategy even with noisy inputs. This approach not only enhances the reliability of these agents but also paves the way for their integration into diverse fields, from autonomous robotics and resource management to personalized healthcare and financial modeling.

The exploration of policy gradients and actor-critic methods, as detailed within the document, inherently demands a testing of boundaries. One might observe that Ada Lovelace keenly understood this principle, stating, “The Analytical Engine has no pretensions whatever to originate anything. It can do whatever we know how to order it to perform.” This aligns with the core idea of reinforcement learning-the agent operates within defined parameters, its success reliant on the quality of the reward function and the exploration strategy. Just as the Analytical Engine requires precise instruction, the agent’s policy must be carefully crafted and iteratively refined through trial and error, revealing the limits and possibilities of the defined system. The document’s emphasis on continuous action spaces and algorithms like PPO further underscores this process of iterative testing and boundary pushing.

What’s Next?

The current reliance on Markov Decision Processes feels… tidy. Too tidy. It assumes the world conveniently resets after each action, a fiction easily exploited in simulation but glaringly absent in sustained, real-world deployment. One wonders if the true challenge isn’t perfecting policy gradients, but abandoning the insistence on a clean slate. Perhaps the ‘bug’ isn’t the instability of learning, but the insistence on forgetting.

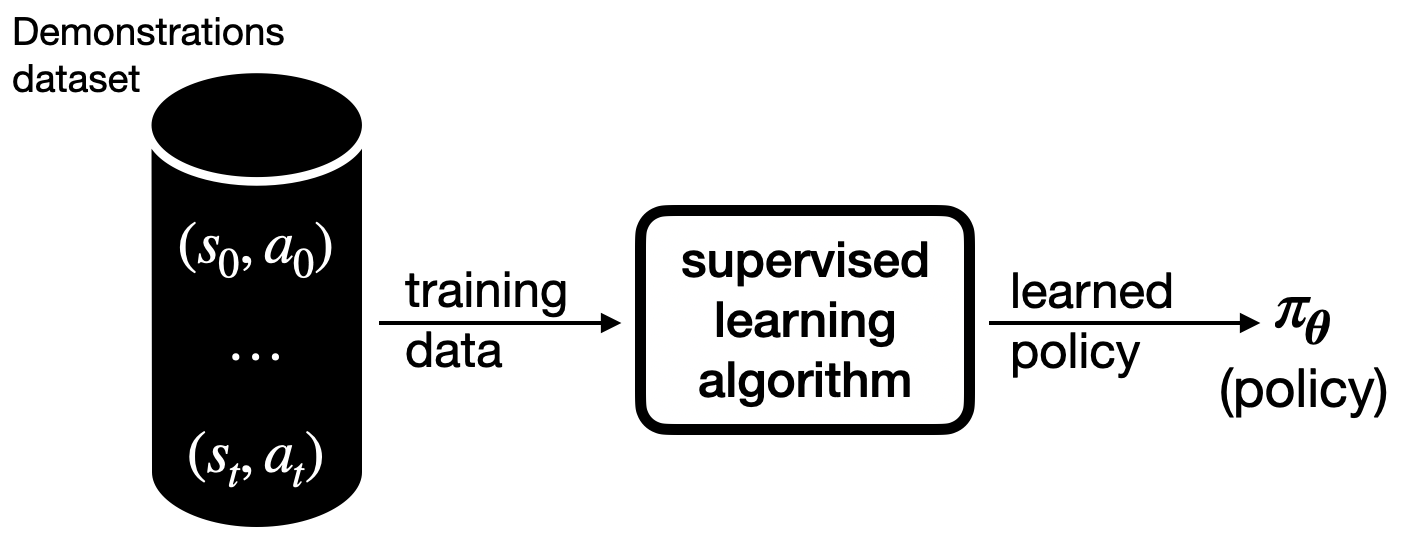

Imitation learning offers a bypass, a shortcut to competence. Yet, it inherently limits exploration, enshrining the biases – and inefficiencies – of the demonstrator. The field seems poised to ask: can a system learn to critique the demonstration, to identify and correct the flaws within the expert’s own behavior? Or will it forever remain a sophisticated mimic?

The scaling of deep neural networks is undeniable, but it feels increasingly like a brute-force solution. The pursuit of ever-larger models begs the question: are these systems genuinely ‘learning’ principles, or simply memorizing vast datasets of successful (and unsuccessful) trajectories? The next breakthrough may not lie in deeper networks, but in a fundamentally different representation-one that prioritizes causal understanding over correlative pattern recognition.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2512.08052.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Clash Royale Best Boss Bandit Champion decks

- Best Hero Card Decks in Clash Royale

- Clash Royale Witch Evolution best decks guide

- Clash Royale December 2025: Events, Challenges, Tournaments, and Rewards

- Best Arena 9 Decks in Clast Royale

- Clash of Clans Meltdown Mayhem December 2025 Event: Overview, Rewards, and more

- Cookie Run: Kingdom Beast Raid ‘Key to the Heart’ Guide and Tips

- JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure: Ora Ora Overdrive unites iconic characters in a sim RPG, launching on mobile this fall

- Best Builds for Undertaker in Elden Ring Nightreign Forsaken Hollows

- Clash of Clans Clan Rush December 2025 Event: Overview, How to Play, Rewards, and more

2025-12-10 23:32