Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research explores whether refining large language models with small amounts of human behavioral data can improve their ability to simulate human reasoning and decision-making.

Finetuning on limited human samples can enhance behavioral simulation, alignment, and belief-action coherence in large language models, though replicating full human responses remains a challenge.

Despite growing interest in leveraging large language models (LLMs) for behavioral research, concerns remain regarding their capacity to accurately replicate human responses and introduce bias. This study, ‘Can Finetuning LLMs on Small Human Samples Increase Heterogeneity, Alignment, and Belief-Action Coherence?’, investigates whether fine-tuning LLMs on limited human data can improve their performance in simulating complex behaviors. Results demonstrate substantial gains in heterogeneity, alignment with human responses, and coherence between stated beliefs and actions following fine-tuning. However, even with these improvements, LLM-generated data struggle to fully reproduce established experimental findings, raising the question of their suitability for replacing human participants in formal inferential analyses and suggesting a role for LLMs in prototyping rather than direct substitution.

The Erosion of Behavioral Fidelity in Language Models

Though large language models excel at generating text that mimics human communication, a significant limitation lies in their capacity to replicate the subtleties of real-world behavior. These models often produce responses that, while grammatically correct and contextually relevant, lack the unpredictable variations and individual quirks that characterize authentic human interactions. This isn’t simply a matter of stylistic differences; the core issue resides in the models’ tendency to oversimplify complex motivations and emotional responses. Consequently, while an LLM might successfully describe a scenario, it frequently fails to convincingly enact the nuanced behavioral patterns that would be expected from a diverse population of individuals facing similar circumstances, hindering their applicability in fields demanding accurate social simulations.

The promise of large language models as tools for social science research is currently limited by a significant discrepancy between their outputs and the inherent variability of human behavior. While LLMs can generate text that appears coherent, these models often struggle to replicate the full spectrum of responses observed in real-world populations, tending toward predictable or average answers. This lack of nuance poses challenges for studies aiming to understand complex social phenomena, as LLM-generated data may not accurately reflect the diversity of opinions, beliefs, and actions present in a given population. Consequently, researchers must carefully consider the potential for identity flattening and other biases when utilizing LLMs, as the models’ limitations could lead to skewed results and inaccurate conclusions about human social dynamics.

Contemporary large language models, despite their capacity for generating human-like text, often struggle to represent the rich diversity present within real-world populations, a phenomenon termed ‘identity flattening’. This occurs because models, trained on vast datasets, tend to converge on statistically dominant traits, effectively smoothing over the nuances of individual experiences and group characteristics. Consequently, LLMs may portray subgroups – whether defined by demographics, socioeconomic status, or personal beliefs – as remarkably similar, failing to capture the considerable internal variation that defines them in reality. This simplification isn’t merely an aesthetic limitation; it fundamentally impacts the validity of using these models in social science research, where accurate representation of heterogeneity is crucial for drawing meaningful conclusions about human behavior and societal dynamics. The result is a distorted mirror reflecting a world where individuality is diminished and the complexities of identity are significantly underestimated.

Refining Simulated Behavior Through Targeted Finetuning

Large Language Model (LLM) finetuning involves taking a pre-trained LLM – a model already exposed to a massive general dataset – and further training it on a smaller, specialized dataset. This adaptation process modifies the model’s internal parameters to optimize performance on the targeted task, in this case, behavioral simulation. Rather than building a model from scratch, finetuning leverages existing knowledge, reducing computational costs and training time. The process typically involves supervised learning, where the model is presented with input-output pairs related to desired behaviors, and reinforcement learning, where the model receives feedback on its actions. Successful finetuning can significantly improve the accuracy and realism of simulated human behavior compared to relying solely on the pre-trained model’s general knowledge.

Successful Large Language Model (LLM) finetuning relies on datasets sourced from controlled behavioral experiments designed to replicate the complexities of human decision-making processes. These experiments typically involve presenting subjects with defined scenarios and recording their responses, including choices, reaction times, and stated preferences. The resulting data captures not just what decisions humans make, but also the subtle factors influencing those decisions – risk aversion, cognitive biases, and contextual sensitivities. Data quality is paramount; experiments must employ rigorous methodologies, large participant pools, and standardized stimuli to ensure the generated data accurately reflects genuine human behavior and minimizes experimental noise. This nuanced data then serves as the training signal for LLMs, enabling them to move beyond generic responses and generate outputs that more closely align with observed human behavioral patterns.

Value-action coherence, as applied to Large Language Models, quantifies the alignment between stated values and resulting actions within generated text. Recent finetuning methodologies utilizing human behavioral data have demonstrated a reduction of the ‘Value-Action Gap’ – the discrepancy between expressed values and subsequent actions – to a range of 23.8-24.4%. This represents a significant improvement, as this gap in LLMs closely approaches the 24.7% observed in human decision-making, suggesting the models are increasingly mirroring human behavioral consistency. The metric is calculated by assessing the logical connection between value statements and actions described in the LLM’s output, with lower percentages indicating greater coherence.

Validating Behavioral Realism: Distributional Alignment and Regression Recovery

Regression coefficient recovery assesses the fidelity of patterns learned by Large Language Models (LLMs) when generating data intended to mimic human behavior. This technique involves building regression models – statistical relationships between variables – on both the human behavioral data and the LLM-generated data. Researchers then compare the regression coefficients – the estimated effect of each variable – from these two models. High recovery rates, indicating similar coefficient values, suggest the LLM is effectively replicating the relationships present in the original human data; discrepancies indicate a failure to capture those relationships accurately. This approach provides a quantitative measure of how well the LLM reproduces not just the statistical properties, but also the structure of the human behavioral data, going beyond simple distributional similarity.

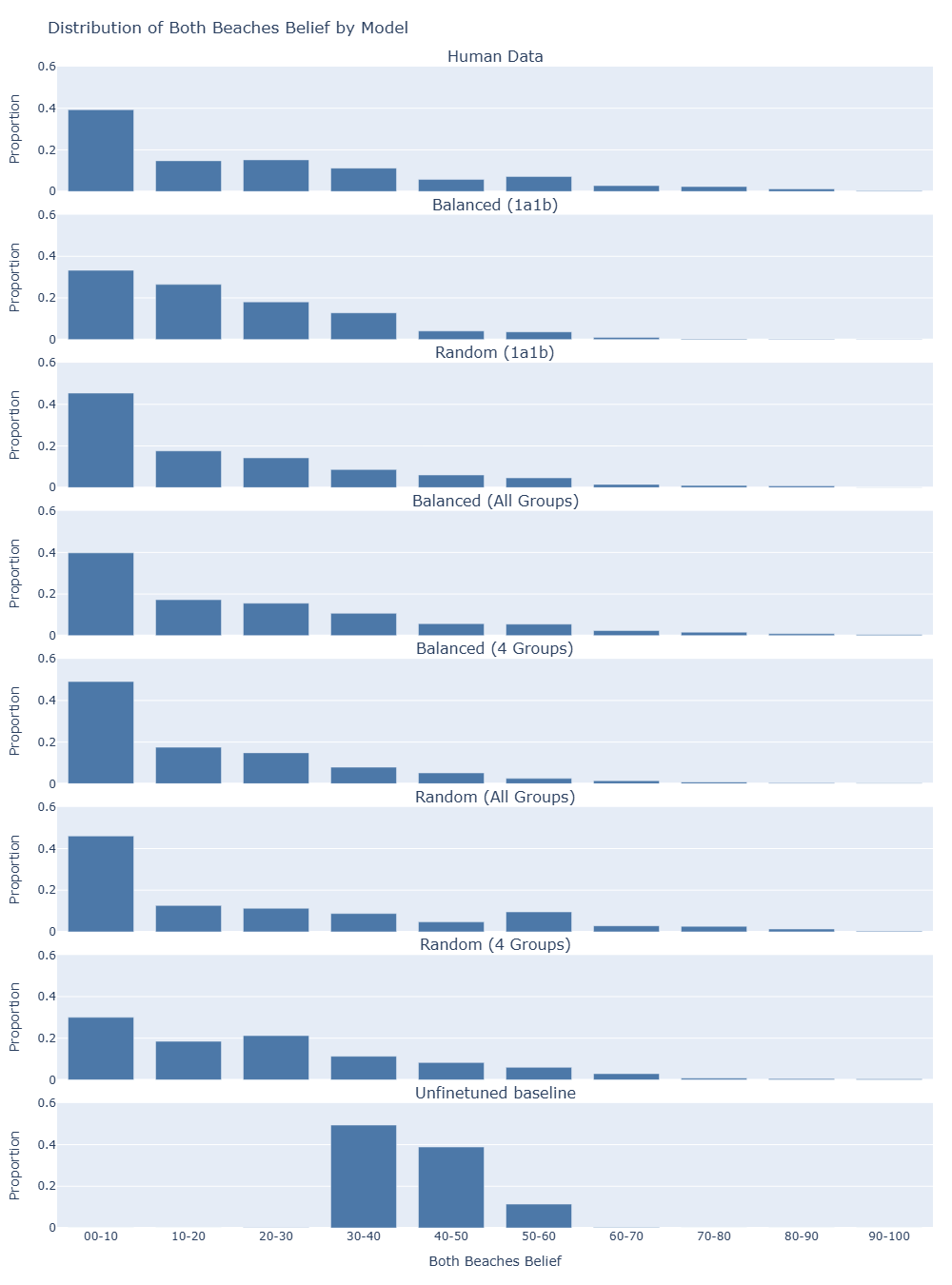

Distributional alignment assesses the similarity between the probability distributions of responses generated by large language models (LLMs) and those produced by humans. This is quantitatively measured using metrics such as Jensen-Shannon Distance (JSD), which calculates the divergence between two probability distributions; lower JSD values indicate greater similarity. Recent research demonstrates a significant improvement in distributional alignment through fine-tuning, achieving at least a 50% reduction in JSD compared to baseline, unfinetuned LLMs. This reduction suggests the fine-tuned models more closely replicate the response patterns observed in human data, indicating a higher degree of behavioral realism in generated outputs.

Validation of Large Language Model (LLM) generated data against human behavioral data requires careful attention to potential biases present in the human data itself. Specifically, ‘social desirability bias’-the tendency of respondents to answer questions in a manner that will be viewed favorably by others-can distort observed behavioral patterns. This bias introduces systematic error, potentially leading to inaccurate assessments of LLM performance; an LLM replicating this biased human data would not necessarily be considered an accurate model of true human behavior. Researchers must therefore employ techniques to identify and mitigate the effects of social desirability bias, such as utilizing implicit measurement methods or statistical adjustments, to ensure a valid comparison and accurate evaluation of distributional alignment between LLM outputs and genuine human responses.

The Potential for Nuance: Small Sample Finetuning and Mitigating Demographic Bias

Recent investigations demonstrate that substantial improvements in large language model (LLM) behavior are achievable even with remarkably limited data – a technique known as ‘small sample size’ finetuning. This approach challenges the conventional wisdom that LLMs require massive datasets for meaningful adaptation, offering a practical solution to the significant costs and logistical challenges associated with extensive data collection. Researchers have found that finetuning with as few as several examples can significantly alter an LLM’s responses, increasing its ability to reflect nuanced human beliefs and perspectives. This not only lowers the barrier to entry for customizing LLMs for specific applications but also opens opportunities for tailoring models to represent diverse viewpoints where large, representative datasets are unavailable.

Large language models are frequently trained on datasets that disproportionately represent individuals from Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic (WEIRD) societies, raising concerns about systematic biases in their outputs and limited applicability to broader populations. Researchers are actively investigating how this overrepresentation manifests in LLM responses, potentially leading to culturally insensitive or inaccurate generalizations when applied to diverse contexts. Studies reveal that models trained on WEIRD-centric data may exhibit diminished performance or produce skewed results when processing information related to non-WEIRD cultures, beliefs, or experiences, hindering their reliable use in global applications and reinforcing existing societal inequalities. This line of inquiry aims to develop strategies for mitigating these biases, including data augmentation techniques and the creation of more representative datasets, ultimately striving for LLMs that exhibit fairness and generalizability across all demographic groups.

Recent investigations demonstrate that even a modest infusion of human-generated data can dramatically reshape the internal landscape of large language models. Specifically, finetuning these models with as few as 30 examples yields a substantial increase in ‘Heterogeneity’ – a measure of the diversity of belief structures the model can represent. Prior to finetuning, a model might exhibit only 19 distinct perspectives; however, after exposure to this limited dataset, the number of unique belief structures expands to over 200. This suggests that LLMs possess a latent capacity for nuanced thought, and that targeted finetuning – even with minimal data – can unlock a far richer and more varied internal representation of the world, moving beyond monolithic responses towards a more complex understanding of human beliefs.

The study’s findings suggest a natural lifecycle for these large language models; while finetuning enhances behavioral simulation – bringing them closer to mirroring human responses – complete replication proves elusive. This echoes a fundamental truth about complex systems: improvements, however significant, introduce new forms of divergence. As John McCarthy observed, “It is better to be vaguely right than precisely wrong.” The research highlights that LLMs are valuable tools for prototyping experimental designs, offering a rapid means of exploration. However, the inherent limitations in achieving perfect behavioral coherence confirm that these models, like all architectures, exist within a temporal framework, evolving and diverging over time, rather than offering static, perfect substitutes for human complexity.

What Lies Ahead?

The pursuit of behavioral simulation through large language models reveals a fundamental tension. This work demonstrates incremental gains in mirroring human responses, yet it simultaneously underscores the inherent limitations of such an approach. Every abstraction carries the weight of the past; the model, trained on a finite sample, will always represent a distillation – and thus a distortion – of the lived experience it attempts to replicate. The improvements in heterogeneity and alignment are not endpoints, but merely shifts in the nature of the approximation.

Future work must acknowledge this fundamental asymmetry. The goal should not be perfect substitution, an illusion destined to fail, but rather the development of LLMs as sophisticated prototyping tools. The value lies not in creating digital twins, but in rapidly iterating through potential behavioral scenarios, identifying vulnerabilities, and testing hypotheses with a speed unavailable through traditional methods.

Ultimately, the longevity of this research path depends on embracing slow change. The pursuit of ever-larger datasets and more complex architectures will yield diminishing returns. True resilience lies in understanding the limits of simulation, and focusing on the development of models that age gracefully – acknowledging their inherent imperfections and adapting to the evolving landscape of human behavior.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2511.21218.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Clash Royale Best Boss Bandit Champion decks

- Clash Royale Furnace Evolution best decks guide

- December 18 Will Be A Devastating Day For Stephen Amell Arrow Fans

- Clash Royale Witch Evolution best decks guide

- Now That The Bear Season 4 Is Out, I’m Flashing Back To Sitcom Icons David Alan Grier And Wendi McLendon-Covey Debating Whether It’s Really A Comedy

- All Soulframe Founder tiers and rewards

- Riot Games announces End of Year Charity Voting campaign

- Mobile Legends X SpongeBob Collab Skins: All MLBB skins, prices and availability

- Deneme Bonusu Veren Siteler – En Gvenilir Bahis Siteleri 2025.4338

- Supercell to resurrect Clash Mini with Clash Royale in June 2025 as part of a new strategy platform

2025-11-30 07:26