Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research suggests that while AI tools can help with coding tasks, over-reliance on them may actually impede the development of core programming skills.

AI assistance during coding can hinder fundamental skill formation, even without impacting task completion speed.

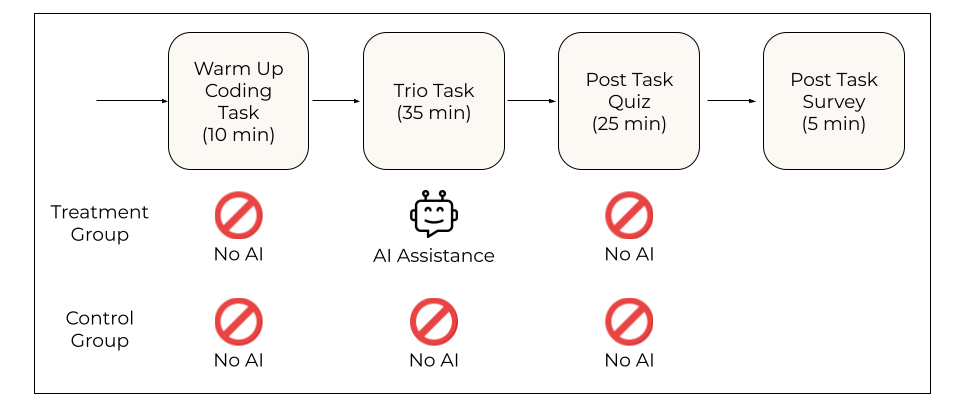

While artificial intelligence promises productivity gains across numerous professional fields, a critical question remains regarding its impact on fundamental skill development. This concern motivates ‘How AI Impacts Skill Formation’, a study investigating how reliance on AI assistance affects the acquisition of expertise, specifically within the context of software development. Our randomized experiments reveal that while AI can offer short-term efficiency, it often impairs conceptual understanding, code reading, and debugging abilities-suggesting that AI-enhanced productivity isn’t necessarily a shortcut to competence. Given these findings, how can workflows be designed to thoughtfully integrate AI assistance and safeguard crucial skill formation, particularly in domains where human expertise is paramount?

The Illusion of Progress: Skill vs. Syntax in Modern Code

The relentless pace of innovation in software engineering necessitates perpetual learning, yet conventional educational approaches frequently prove inadequate for cultivating true mastery. Traditional methods often prioritize memorization of syntax and APIs over the underlying principles that enable developers to adapt to novel technologies and solve complex problems. This discrepancy arises because software development isn’t simply about knowing tools, but about understanding computational thinking, design patterns, and the ability to decompose challenges into manageable components. Consequently, developers may find themselves proficient in using existing libraries without possessing the fundamental knowledge to debug effectively, optimize performance, or contribute meaningfully to new frameworks – a situation that hinders both individual growth and the broader advancement of the field.

Contemporary software development increasingly relies on intricate tools and libraries, notably asynchronous programming frameworks, which present a significant challenge to traditional learning approaches. Simply memorizing syntax or API calls proves insufficient for mastery; instead, a robust conceptual understanding of the underlying principles-such as event loops, concurrency models, and non-blocking operations-is crucial. These frameworks demand developers internalize how and why code functions, not merely what it does, enabling effective debugging, adaptation to novel situations, and ultimately, the creation of scalable and maintainable applications. Without this conceptual foundation, developers risk becoming lost in a sea of implementation details, hindering their ability to effectively leverage these powerful tools and innovate within the rapidly evolving software landscape.

Truly mastering software development isn’t simply about writing code; it’s a cyclical process built upon actively doing, systematically addressing mistakes, and deeply understanding existing codebases. Skill formation isn’t linear; it demands a constant interplay between creation, debugging, and comprehension. However, this crucial cycle is often disrupted by the sheer complexity of modern software projects. When tasks become overwhelmingly intricate-involving numerous dependencies or abstract concepts-the ability to experiment, identify errors, and effectively dissect code diminishes. Consequently, developers may resort to copying and pasting solutions without genuine understanding, hindering the development of robust, adaptable skills and ultimately limiting their capacity for innovation.

The Siren Song of Assistance: A Double-Edged Sword

Skill acquisition during complex tasks benefits from both human and artificial intelligence-driven assistance. Guidance, whether provided by a mentor or an AI tool, can decompose challenging problems into manageable components, offer immediate feedback on performance, and suggest alternative approaches when learners encounter difficulties. This support structure allows individuals to bypass cognitive bottlenecks, accelerate the learning process, and develop a more robust understanding of the underlying concepts. The effectiveness of this assistance is predicated on the quality of the support provided and its alignment with the learner’s current skill level and learning objectives.

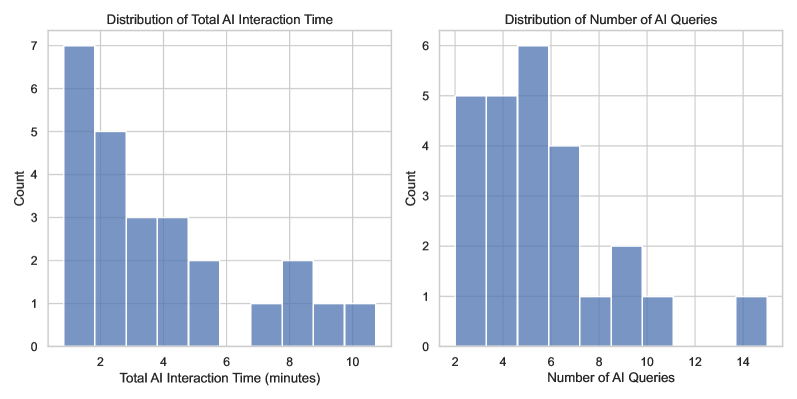

The efficacy of AI assistance is directly correlated with the quality of interactions initiated by the user, specifically through ‘AI_Querying’, and the skill of the developer in crafting effective ‘Prompts’. Poorly formulated queries or prompts will likely yield irrelevant or inaccurate responses, diminishing the potential benefits of AI support. Successful implementation requires precise and detailed instructions to the AI model, outlining the specific information or assistance needed. Furthermore, iterative refinement of prompts based on received responses is crucial to guide the AI toward a useful and accurate outcome; a one-time, broadly-defined prompt is unlikely to deliver optimal results. The developer’s ability to decompose complex problems into manageable prompts and to evaluate the AI’s output for correctness remains a critical factor in leveraging AI as a learning aid.

While AI tools offer the potential to accelerate learning through rapid information access and debugging assistance, the observed impact is contingent on substantial periods of ‘Active_Coding_Time’. Our research indicates a counterintuitive effect: the utilization of AI assistance during coding tasks demonstrably reduced skill formation. This suggests that relying on AI to circumvent challenges or provide direct solutions may hinder the development of foundational coding abilities, despite the efficiency gains in task completion. The benefit of AI-assisted learning, therefore, appears limited when used as a substitute for, rather than a complement to, dedicated practice and problem-solving.

The Cognitive Cost of Convenience: Engagement vs. Automation

Cognitive engagement, defined as the mental effort and resources dedicated to a learning task, is fundamentally linked to skill acquisition. Assistance, whether from a human or an AI, impacts this engagement; effective support strategically challenges the learner, prompting active recall and deeper processing, thereby increasing cognitive engagement. Conversely, assistance that preemptively solves problems or reduces the need for mental effort can decrease engagement, leading to shallower understanding and hindering skill formation. The degree to which assistance amplifies or diminishes engagement is directly correlated to the level of challenge and the learner’s active participation in the problem-solving process.

AI assistance tools demonstrably reduce cognitive load during debugging and error handling processes. By automating syntax checking, identifying common errors, and suggesting potential fixes, these tools offload tasks that typically consume significant mental resources. This reduction in immediate cognitive demand frees up working memory and attentional capacity, allowing users to focus on higher-level conceptual understanding of the underlying code and problem-solving strategies. The reallocation of mental resources can facilitate more effective learning and skill development, provided the user remains actively engaged in the process and does not solely rely on the AI-provided solutions.

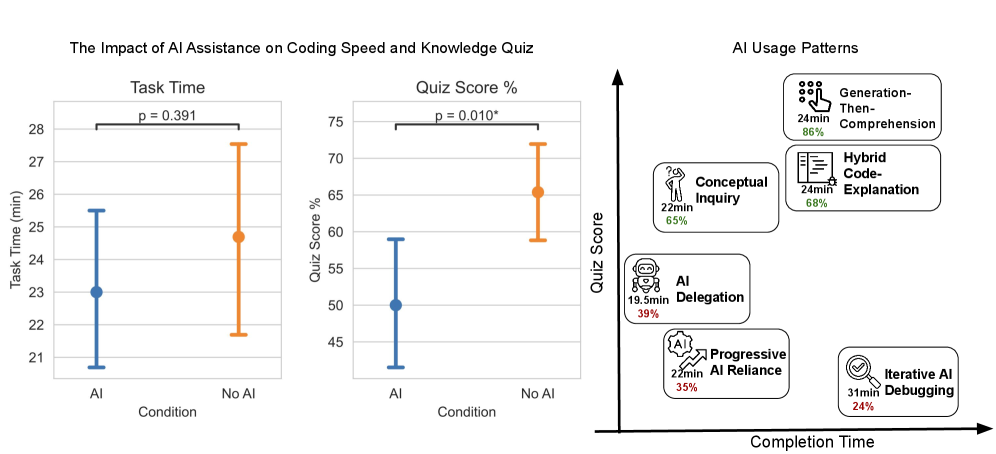

Our research demonstrates that uncritical dependence on AI assistance during problem-solving correlates with diminished conceptual understanding and a reduction in skill acquisition. Specifically, participants utilizing AI support exhibited a 17% decrease in evaluation scores compared to those solving problems independently. This difference was statistically significant, as indicated by a Cohen’s d of 0.738 and a p-value of 0.010, suggesting a moderate to large effect size and confirming that reliance on AI without active engagement negatively impacts the development of independent problem-solving capabilities.

The Trio Paradox: Skill Formation in a Complex System

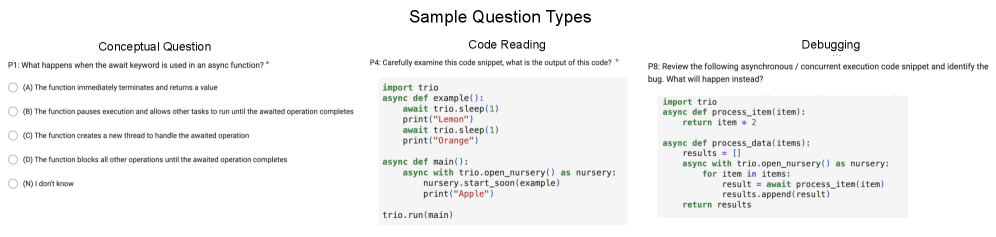

The Trio library presents a uniquely challenging landscape for evaluating the development of programming skill. Unlike simpler concurrency tools, Trio demands a comprehensive understanding of asynchronous programming principles – including tasks, channels, and nurseries – and the nuances of coordinating concurrent operations. Its design intentionally avoids traditional locking mechanisms, forcing developers to embrace a more robust and scalable approach to handling shared state. Consequently, successful utilization of Trio isn’t merely about writing functional code; it requires a deep conceptual grasp of concurrency, coupled with the ability to effectively diagnose and resolve the subtle bugs that inevitably arise in parallel systems. This complexity makes it an ideal platform for studying how developers acquire and demonstrate proficiency in modern, asynchronous programming paradigms.

Effective utilization of the Trio concurrency library extends beyond merely writing functional code; it demands a robust understanding of asynchronous programming principles and a developed capacity for debugging concurrent systems. Unlike traditional synchronous programming, asynchronous code introduces complexities related to task scheduling, data sharing, and potential race conditions. Consequently, developers must not only implement the desired functionality but also reason about the interplay of concurrent tasks and proactively identify and resolve issues that may not manifest in sequential code. This requires a deeper cognitive engagement with the code, involving mental simulations of execution paths and a systematic approach to isolating the source of errors when concurrency introduces unexpected behavior.

While artificial intelligence tools offer potential support in complex programming tasks, such as utilizing the asynchronous concurrency library Trio, their impact on developer skill acquisition is nuanced. Recent investigations reveal that, contrary to expectations, reliance on AI assistance during the skill-building process actually resulted in a statistically significant reduction in overall competency. Specifically, developers who utilized AI support demonstrated a 17% decrease in evaluation scores – a substantial effect size indicated by Cohen’s d of 0.738 (p=0.010). This suggests that the benefit of AI isn’t automatic; its effectiveness is contingent upon the developer’s pre-existing ability to frame precise prompts and, crucially, to critically assess the validity of the AI’s generated solutions – skills that, if underdeveloped, can be undermined by over-reliance on automated assistance.

The pursuit of efficiency, often accelerated by tools like AI assistance, frequently overshadows the cultivation of foundational expertise. This research into skill formation highlights a predictable truth: shortcuts, while expedient, can erode the very abilities they aim to supplement. It’s a pattern observed across countless technological shifts. As Edsger W. Dijkstra once stated, “It’s intellectually dishonest to be satisfied with answers that are not understood.” The study demonstrates that while AI might maintain output, it simultaneously undermines the development of core coding skills – a subtle trade-off few acknowledge until the system inevitably requires deeper intervention. The illusion of progress, fueled by readily available assistance, often masks a gradual decline in genuine competence. Production will, as always, find a way to expose these vulnerabilities.

The Road Ahead (and the Potholes)

The observation that readily available AI assistance can subtly erode foundational skill development isn’t exactly a shock. Anything called ‘skill formation’ implies an endpoint, a mastery, and that’s always a moving target. Production code, predictably, doesn’t care about elegant pedagogical curves. It cares about deadlines. This research, therefore, simply highlights the inevitable trade-off: speed now, competence later – and later often never arrives. The focus on coding is useful, but the pattern will generalize. Expect to see the same dynamic play out across any domain where AI offers a convenient cognitive offloading path.

Future work will undoubtedly explore ‘mitigation strategies’ – interventions designed to preserve skill development while still leveraging AI’s benefits. These will likely involve contrived exercises, carefully curated learning paths, or some form of ‘skill audit’ embedded within the development workflow. Such efforts are laudable, but one suspects they will be Sisyphean. The incentive structures remain misaligned. It’s easier to ask the machine, faster to copy-paste, and the consequences of skill atrophy are usually deferred.

Perhaps the truly interesting question isn’t how to prevent skill erosion, but how to manage it. What does a workforce look like where fundamental competence is increasingly outsourced to algorithms? What new skills – meta-skills, perhaps – will be required to effectively orchestrate and validate AI-generated outputs? Better one deeply understood monolith of human expertise than a hundred lying microservices of brittle, AI-dependent shortcuts.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.20245.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Heartopia Book Writing Guide: How to write and publish books

- Lily Allen and David Harbour ‘sell their New York townhouse for $7million – a $1million loss’ amid divorce battle

- EUR ILS PREDICTION

- VCT Pacific 2026 talks finals venues, roadshows, and local talent

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Battlestar Galactica Brought Dark Sci-Fi Back to TV

- How to have the best Sunday in L.A., according to Bryan Fuller

- Simulating Society: Modeling Personality in Social Media Bots

- January 29 Update Patch Notes

- Love Island: All Stars fans praise Millie for ‘throwing out the trash’ as she DUMPS Charlie in savage twist while Scott sends AJ packing

2026-01-29 20:21