This essay has been developed based on the book “La Bamba: A Visual History,” authored by Merrick Morton, which was published by Hat & Beard Press.

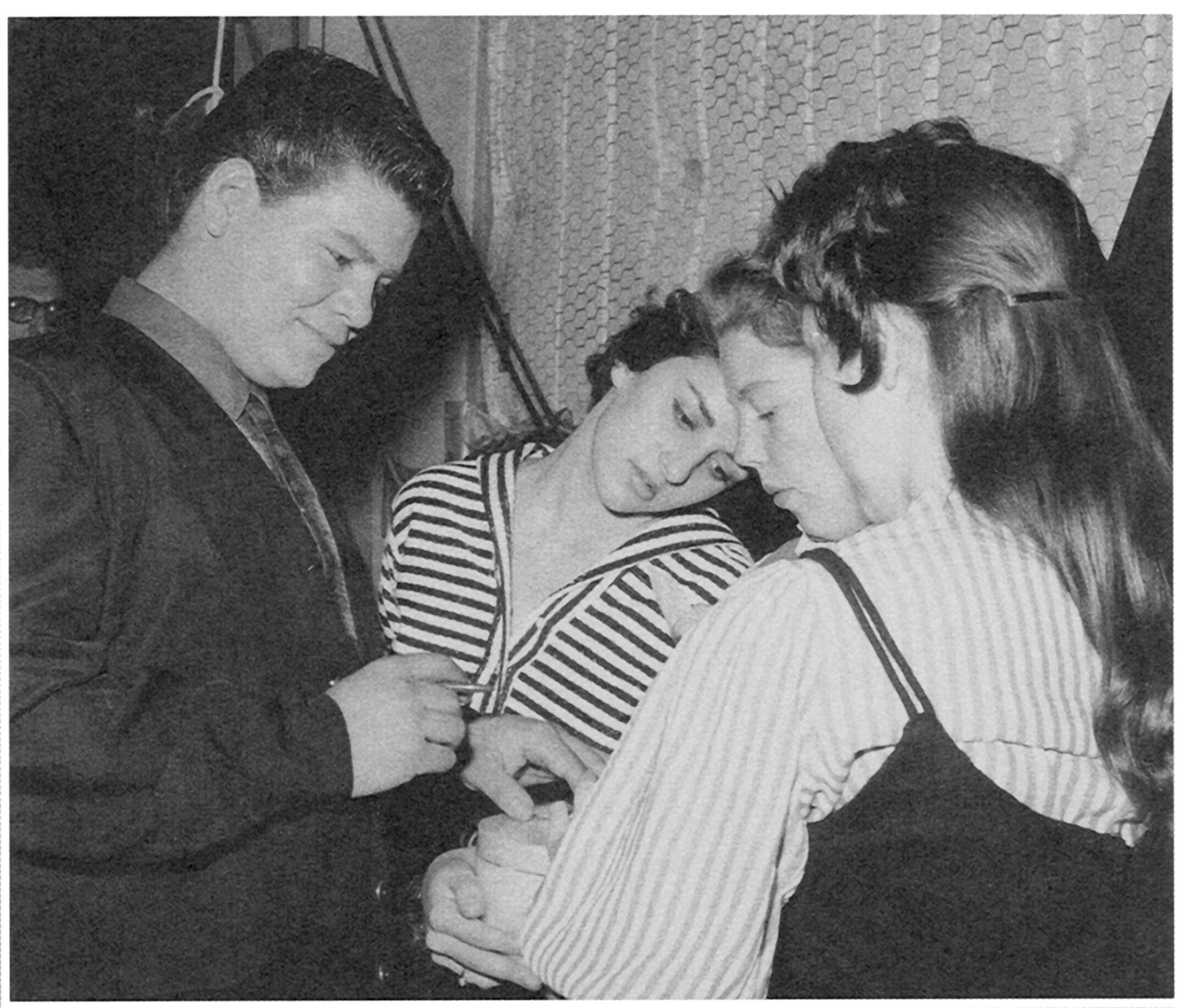

The flyer announced: ‘Dance, dance, dance! Enjoy the music of The Silhouettes Band!’ This band, featuring the talented Ritchie Valens, also known as ‘the fabulous Lil’ Richi and his Sobbing Guitar,’ appeared at the San Fernando American Legion Hall in Southern California back in 1958.

As a passionate movie buff reminiscing on my past, I was sixteen years old when The Silhouettes became my first band. This group catapulted me into the annals of history, yet the enigmatic essence of a silhouette is what truly captivates me. You can make out the overall form without fully grasping the figure creating the shadow. For me, Valens’ musical journey commenced with The Silhouettes, and ever since he moved on, we’ve been piecing together his narrative and projecting our own experiences onto it.

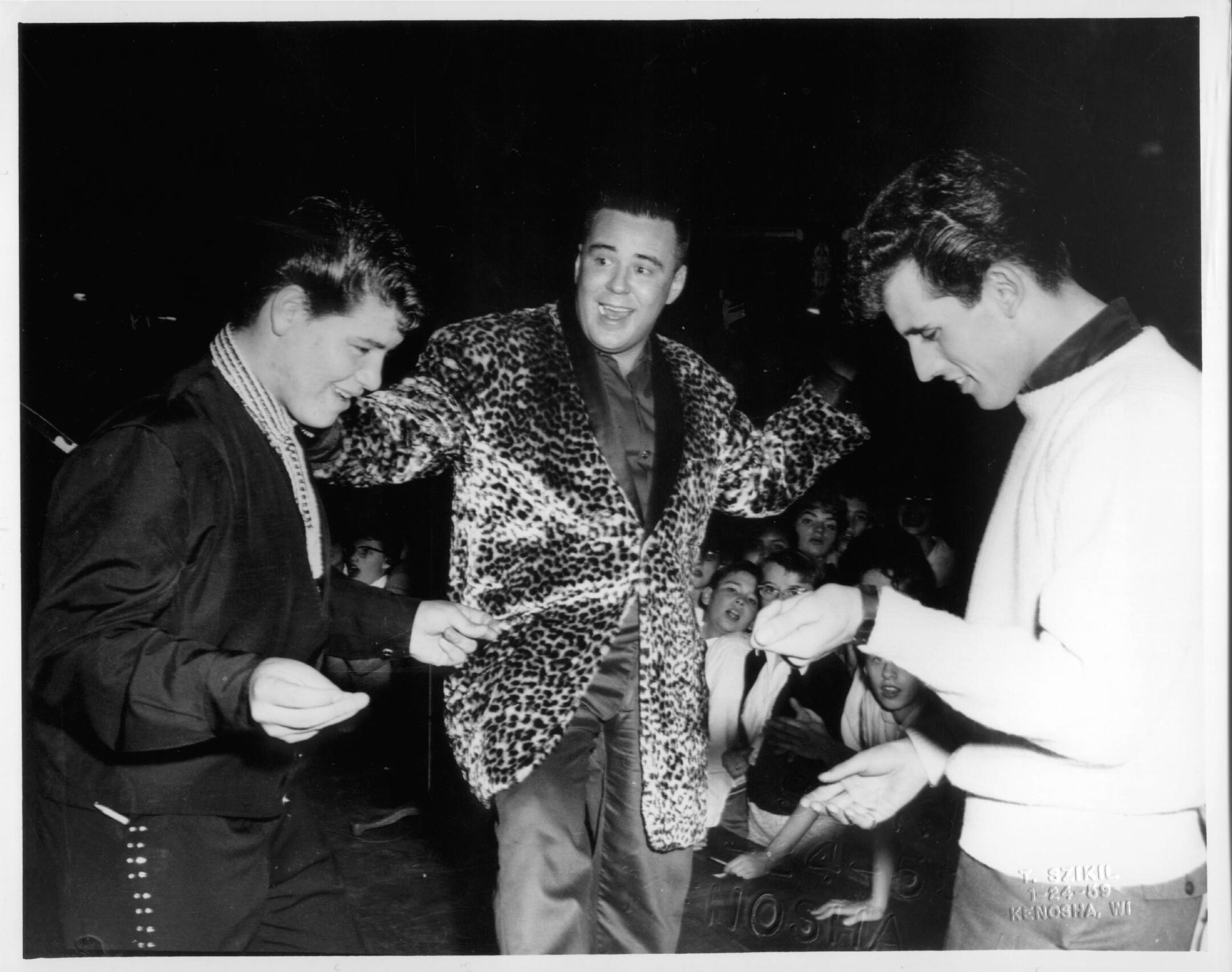

In the realm of rock ‘n’ roll, he was a pioneer, but his life would be tragically cut short just a year later. On February 3, 1959, during an Iowa blizzard, the plane transporting members of the Winter Dance Party Tour – Buddy Holly, the Big Bopper, and Ritchie Valens – met with a devastating crash, claiming their lives. Known as a Chicano icon, he remains a mysterious figure.

As a youngster, Ritchie would strum his guitar to earn money for his family, one of the tunes he played being a rendition of “Malagueña.” This melody stemmed from centuries-old Spanish flamenco music that had expanded globally, transforming into a renowned classical piece and a frequently used soundtrack in Hollywood films by the 1950s. In his skilled hands, it served as a launchpad for iconic guitar solos.

In the American Legion Hall, “Malagueña” shared his unique blend of charm and rhythm with his audience. At the same time, his mother peddled homemade tamales at these shows. This innocent 17-year-old Chicano boy from Pacima found an unconventional yet captivating way to present himself to America, by taking something commonplace and transforming it into something fresh and unfamiliar.

From the get-go, I’ve always marveled at Ritchie’s knack for breathing new life into familiar tunes. As a young man, he demonstrated an extraordinary ability to transform a song, which in turn, seemed like a means of self-transformation. Listening to “Donna,” a tender love ballad that resonated deeply with Chicano listeners, many of whom had long been captivated by Black vocal groups, I can’t help but appreciate how Ritchie paved the way for an influx of remarkable Chicano soul music in the ensuing two decades.

Undeniably, you should give “La Bamba” a listen. This timeless melody hails from Veracruz, Mexico, and its rhythm carries traces of African, Spanish, Indigenous, and Caribbean influences. In the film, Valens experiences this song for the first time when his brother Bob leads him to a brothel in Tijuana, but regardless of how he initially discovered it, Valens saw the song as a means to express himself powerfully through his voice and guitar.

The music he created had roots in Mexico and Los Angeles during the 1940s. This unique blend was formed by merging Spanish-language swing rhythms, Black doo-wop harmonies, and country-style guitar strumming, much like ingredients being mixed together in a mortar and pestle (molcajete y tejolote). Primarily, it was the radio that played a significant role in this fusion, bringing together sounds that were dissimilar to what had been heard before and broadcasting them on AM stations throughout Southern California. Radio acted as a consuming force, absorbing differences and transforming them. If Ritchie is now seen as a trailblazer of Chicano music, he was essentially the embodiment of radio democracy during his short-lived career, with a spotlight illuminating him as a distinct figure in the cultural landscape.

Danny Valdez was well-versed in all the songs during the 1970s. Known as both an artist and activist, he released “Mestizo”, which is considered the first Chicano protest album to be distributed by a major label at that time. With his friend Taylor Hackford, they would often drink beer, sing Ritchie Valens tunes, and discuss grand plans for the future. They dreamed of one day collaborating on a movie, with Valdez playing Ritchie and Hackford directing. However, as Hackford put it, “Neither of us had a cent to our names back then,” which meant their movie project never came to fruition. But after Hackford found success with “An Officer and A Gentleman”, Valdez brought up the idea again.

An upcoming photo album from Hat & Beard Press is set to showcase unpublished photographs of ‘La Bamba’, taken by Merrick Morton, for the first time.

The journey to bring “La Bamba” to the big screen involved several stages, with the focus initially on the music itself. To make the music vibrant and authentic, they relied on a small collection of recordings produced by Bob Keane, which Ritchie Valens had left behind after his untimely death. As the owner of Del-Fi Records, Keane played a significant role in Valens’ life, recording his songs, advising him to change his name from Richard Steven Valenzuela, and offering career guidance. To record “La Bamba”, Keane rented Gold Star Studios at an affordable $15 per hour, and enlisted top session musicians like Earl Palmer and Carol Kaye as Valens’ backup band, including future members of The Wrecking Crew. However, the recordings made were not cutting-edge, even during their own era.

In my perspective as a movie reviewer, I’d say these scenes weren’t top-notch, reminiscent of Ray Charles’ early recordings for Swing Time. I had a vision, a commercial one, where the music would sell the film, leaving audiences humming ‘La Bamba’ even if they were unfamiliar with it beforehand. To achieve this, I required contemporary musicians who not only grasped the essence of Ritchie’s tunes but could also resonate with today’s listeners, a demographic immersed in the music of Michael Jackson, Madonna, and George Michael.

Ritchie’s family, consisting of his mom Connie and his other relatives, had learned earlier that Los Lobos were performing “Come On, Let’s Go” live in East L.A. When the band performed a concert in Santa Cruz, which was where the Valenzuela family resided by the 1980s, a bond developed between them.

Luis Valdez, writer and director, recalls knowing Los Lobos back in the ’70s when they were just beginning their musical journey. At that time, they were simply another band from East L.A. We were lucky because they were at a stage in their career where they could take on our project. Without Los Lobos, we wouldn’t have Ritchie. David Hidalgo’s voice is remarkable; I don’t think we could have found other musicians to replicate it. They hail from East L.A., they are all Chicanos. They were making a tribute. Coincidentally, we bumped into them in the airport when they learned that ‘La Bamba’ had reached number one on the national charts.

According to Hackford, they considered themselves the spiritual successors of Ritchie Valens. They then remade some of Ritchie’s songs and also ones he performed live but didn’t record. Meanwhile, Hackford had an album filled with old tunes that took on a modern twist.

Subsequently, Hackford deliberately arranged for current actors to portray the iconic rockers from the Winter Dance Party Tour. He selected contemporary talents who could also re-create their songs: Marshall Crenshaw assumed the role of Buddy Holly, Brian Setzer took on Eddie Cochran, and Howard Huntsberry played Jackie Wilson.

In the movie, I was taken aback by the initial melody that played – a powerful rendition of “Who Do You Love?” by Bo Diddley. This unexpected collaboration featured Carlos Santana, who was brought on as the soundtrack composer, teaming up with Los Lobos. To top it off, Bo Diddley himself lent his distinctive voice to the mix.

Luis Valdez expressed joy over Carlos Santana’s involvement in Ritchie’s tale, stating, “His touch was a vital part of our story.” Santana’s guitar played a significant role in many scenes, and he even crafted a theme for each character. After viewing the entire movie, Santana was deeply touched by it and eagerly agreed to contribute without hesitation. In the soundstage at Paramount where we recorded his soundtrack, Santana worked his magic with his guitar. This collaboration resulted in a beautiful friendship. It’s remarkable what an artist can achieve.

The original soundtrack recording topped the Billboard pop charts and went double platinum.

Hackford had a fondness for pop tunes; his debut film, “The Idolmaker” (1980), was a musical about rock. The release of popular music was an integral part of the movie’s marketing strategy. Before the 1982 release of “An Officer and a Gentleman,” the hit song “Up Where We Belong” by Joe Cocker and Jennifer Warnes was released, peaking at No. 1 just a week after its premiere. For the 1984 film “Against All Odds,” he chose Phil Collins to perform the theme song, which was released three weeks prior to opening; soon enough, it climbed to the top of the charts. The 1985 film “White Nights” boasted two No. 1 hits – Lionel Ritchie’s “Say You Say Me” and Phil Collins and Marilyn Martin’s duet “Separate Lives.

One challenge facing “La Bamba” was that the general movie-going audience in 1987 was not acquainted with the name Ritchie Valens. Hackford also had strategies to address this issue. He aimed to introduce him to modern viewers – successfully persuading the studio to finance a distinctive teaser trailer, which would be shown several weeks prior to the release of the main movie trailer in cinemas.

The producer gathered well-known individuals for a presentation aimed at reintroducing Valens. The short movie featured Canadian artist Bryan Adams and Little Richard discussing the legend, along with footage of Bob Dylan cruising in a convertible on the Pacific Coast Highway. A 17-year-old Dylan was present at one of Valens’ concerts in Duluth, Minnesota, only a few days before the tragic plane crash; he shared his thoughts about how Valens’ music affected him. “Of course it had an impact,” stated Hackford.

Following the success of the “La Bamba” soundtrack, which was also followed by Volume Two, Los Lobos capitalized on their newfound popularity. They had gained notable fame with “La Bamba,” and they continued this success with “La Pistola y El Corazón,” a raw mix of mariachi and Tejano tunes played on traditional acoustic instruments. By doing so, they introduced many listeners to music that was previously unfamiliar. This album won a Grammy in 1989 for Best Mexican-American Performance.

The “La Bamba” soundtrack paved the way for Latin music to achieve cross-border success on a grand scale in mainstream pop culture. Artists such as Ricky Martin, Jennifer Lopez, Shakira, Bad Bunny, Peso Pluma, Becky G, Anitta, J Balvin, Karol G, and Maluma, among others, have become chart-toppers, amassing billions of streams, leading huge tours and festivals.

Does Hackford think “La Bamba” helped set the table for subsequent Latino pop star success?

It seems likely that Ritchie Valens is the one who arranged the table setting, as he gained immense popularity by recording a Spanish-language rock ‘n’ roll adaptation of a traditional tune, which he turned into a massive hit.

Regardless of the occasion – be it a wedding reception or a bar mitzvah – whenever ‘La Bamba’ plays, the dance floor quickly fills up. This iconic tune is by Ritchie Valens, and rightfully so. We may have followed in his footsteps, but he deserves the recognition for starting this dance craze.

RJ Smith, hailing from Los Angeles, is an accomplished author who’s contributed to various publications such as Blender, the Village Voice, Spin, GQ, and the New York Times Magazine. Among his written works are “The Great Black Way,” a biography of James Brown titled “The One: The Life and Music of James Brown,” and “Chuck Berry: An American Life.

Read More

- Mobile Legends: Bang Bang (MLBB) Sora Guide: Best Build, Emblem and Gameplay Tips

- Brawl Stars December 2025 Brawl Talk: Two New Brawlers, Buffie, Vault, New Skins, Game Modes, and more

- Clash Royale Best Boss Bandit Champion decks

- Best Hero Card Decks in Clash Royale

- Best Arena 9 Decks in Clast Royale

- Call of Duty Mobile: DMZ Recon Guide: Overview, How to Play, Progression, and more

- Clash Royale December 2025: Events, Challenges, Tournaments, and Rewards

- All Brawl Stars Brawliday Rewards For 2025

- Clash Royale Best Arena 14 Decks

- Clash Royale Witch Evolution best decks guide

2025-07-03 02:01