In 1993, French civilization encountered an unprecedented adversary that wasn’t linked to either Nazis or computer-generated dinosaurs. More precisely, the French cinema industry launched a rebellion against Jurassic Park. The French Culture Minister went as far as labeling Steven Spielberg’s blockbuster as a threat to French culture. It might seem an unusual focus for a nation’s anger, and you would be correct. This outrage masked a prolonged decline in the relevance and financial success of French films. By sheer coincidence, Jurassic Park was released in cinemas just before this, making it and its charismatic director the symbol of “imperialism” for no other reason than convenience. This incident became the most awkward crisis in French filmmaking history.

Spielberg Hits a Nerve, and Starts a Turf War

The origin of this situation can be traced back to ordinary bureaucratic matters, involving trade representatives discussing the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). In these discussions, the U.S. representative made an apparently innocent proposal to foster more international connections by eliminating existing quotas and tariffs between Europe and America. However, this suggestion ignited strong opposition, particularly in France, where they have historically restricted American movies and enforced a specific proportion of French-produced content on television.

As stated by Reason, French creators such as filmmakers, actors, and politicians criticized “Jurassic Park” as a potential danger to their national identity. This beloved family movie was seen as a Trojan Horse, capable of undermining European cinema. A particularly pitiful episode in the annals of European art history since the French government rejected Edouard Manet’s painting.

Trade disputes over films are nothing out of the ordinary; protectionism has been around almost as long as movies themselves, and it’s one of the cherished customs and closely guarded secrets of French culture. Consequently, actors like Gérard Depardieu and Isabelle Huppert have appealed to the European Parliament for special considerations. In response, French Culture Minister, Jacques Toubon, expressed concern that an animatronic Triceratops could potentially cause a downfall in the French film industry if left unchecked.

According to the New York Times, this was linked to a supposed conspiracy of the “Anglo-Saxon mercantilist culture,” which encompassed an endless supply of Tom and Jerry cartoons. In essence, director Claude Berri warned that if the GATT agreement were approved as planned, European culture would cease to exist. Fortunately, the US eventually withdrew its demand and didn’t disrupt the current situation. From a theoretical standpoint, France emerged victorious in this scenario.

A War With Only Losers

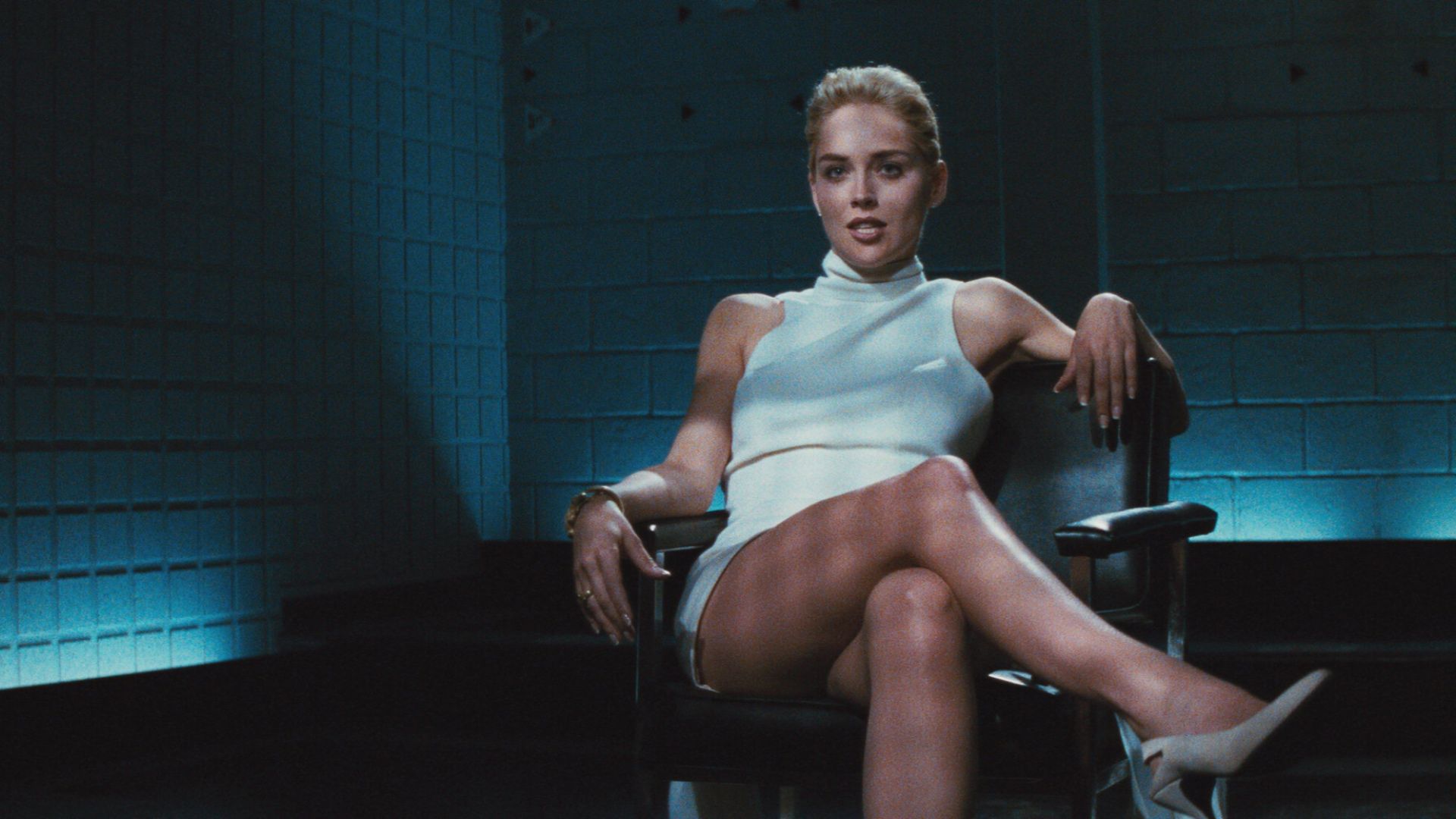

Was it fair that they took action? This question might be subjective depending on your views about quotas and government intervention. However, let me shed some light on a lesser-known fact. In the years leading up to the 1993 protests, French blockbusters, heavily subsidized, consistently underperformed at the box office, with many being historical films. Interestingly, two major movies, “Basic Instinct” and “Highlander II: The Quickening,” which fueled the anti-American sentiment, were actually produced by French companies. These movies had substantial budgets, as evidenced by data from “The Numbers.” Adding fuel to the fire, a film by Berri and Depardieu was released in theaters the same month as “Jurassic Park.” This complicates the debate, as it suggests that the French industry may have been struggling even before the protests.

It’s unclear whether the French are more offended by the hypocrisy of the blockbuster or the fact that a Gaulish production was involved in one of the worst sequels ever made. Nevertheless, they seemed particularly critical of these movies. Interestingly, their criticism didn’t extend to Sylvester Stallone’s Cliffhanger, another summer hit produced by French company Studio Canal, which had financed and later acquired the rights to several successful action films from the defunct Carolco. Whether this was a coincidence is for you to decide.

Soul Searching Turns to Searching for Scapegoats

The excessive grinding of teeth persisted, with French intellectuals seemingly enjoying their role as victims. Depardieu, surprisingly, remained the most modest and rational voice. The film community as a whole seemed to go mad, escalating their dramatic and self-promoting declarations, pondering how they would meet their monthly expenses for Cognac and Gauloises. As portrayed in Some Big Bourgeois Brothel, director Bertrand Tavernier awkwardly likened himself to displaced Native American tribes: instead of saying he was like them, he compared his situation to theirs.

The Americans intend to deal with us much like they handled Native American tribes… If we behave impeccably, they might grant us a reservation; they may offer us the Dakota hills; and should we continue being amiable, perhaps there will be another hill given.

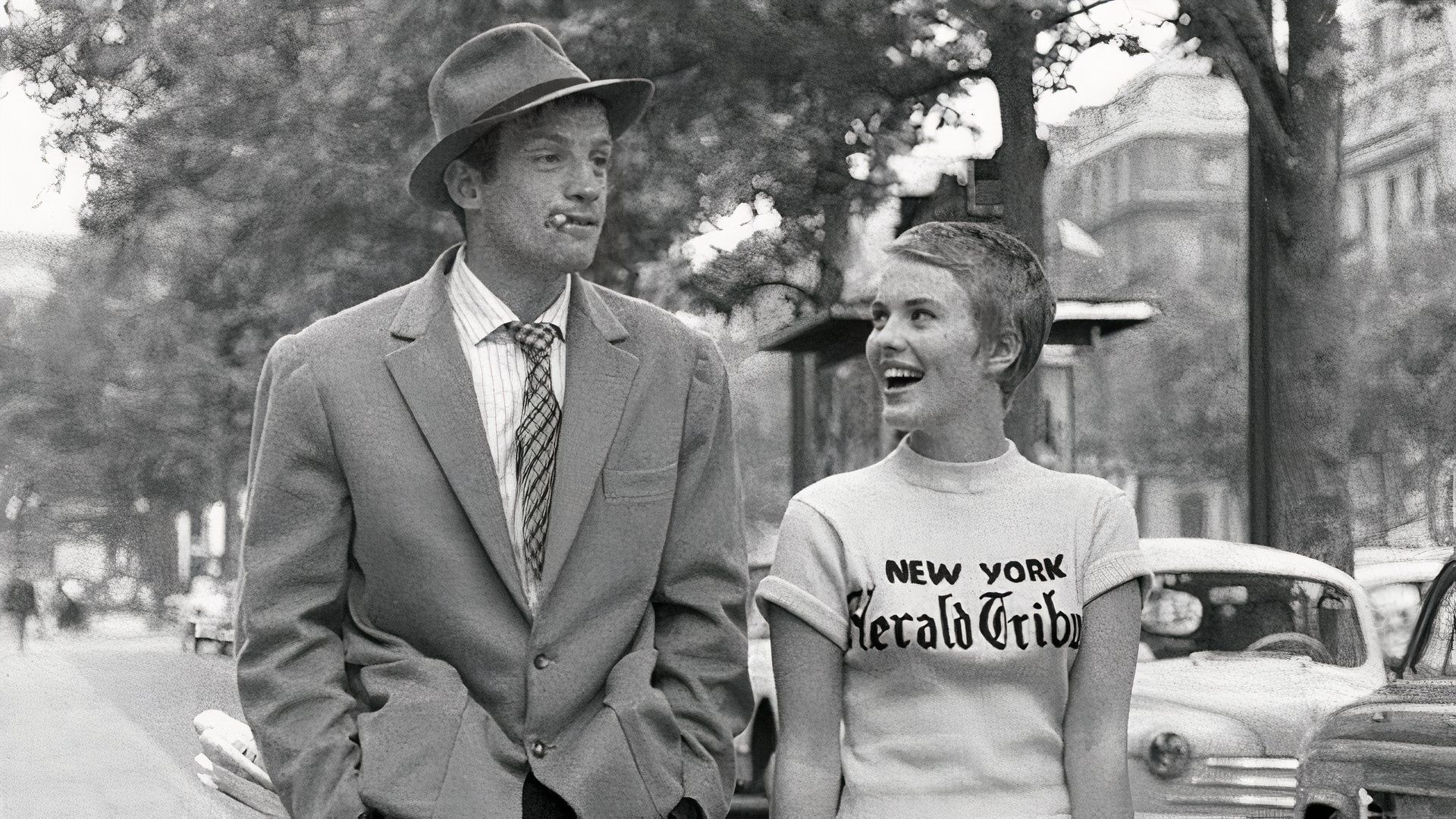

In a quiet moment of introspection, the self-assured French movie industry found itself stirring with a sense of unease. Movies produced within France were no longer commanding attention or even financial success, not just domestically but internationally, as suggested by the data from Box Office Mojo. This uncertainty was the undercurrent to their growing discontent. The charm and enchantment that once defined French cinema, captivating audiences globally, seemed to have vanished. Similarly, the US film industry experienced a transition, moving away from auteur films and focusing on creating movies for global viewers.

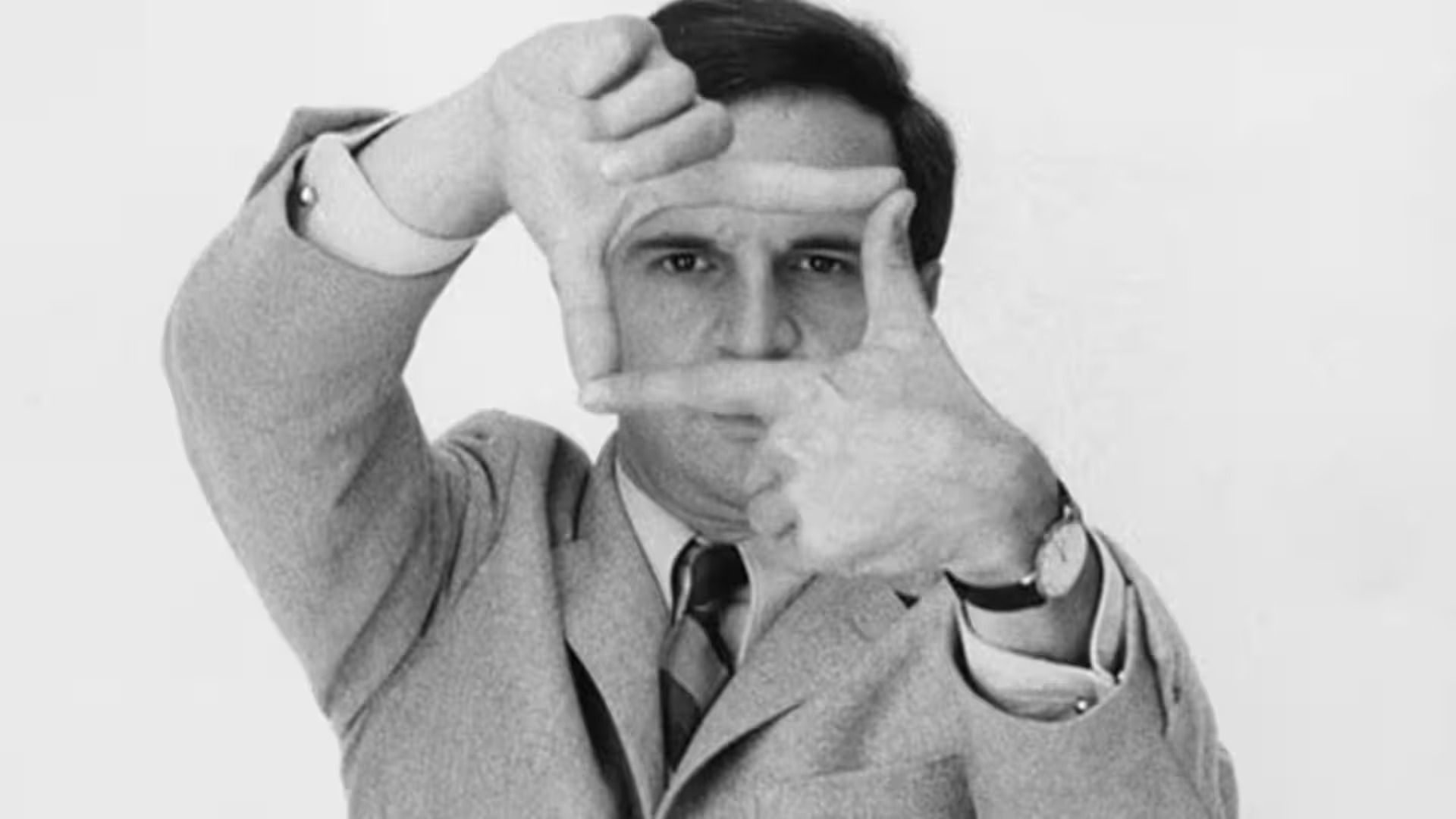

In simpler terms, French cinema adopted a secluded stance with pride, transitioning into a narrow, local focus as filmmakers from Asia and Latin America rose to prominence, filling the gap left by the decline of established figures like Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut, Alain Delon, Catherine Deneuve, and others. By the ’80s, many notable French directors had moved on or were relegated to lesser roles, while the successes of the New Wave era seemed distant memories. Exception to this trend were filmmakers like Luc Besson and Gaspar Noé who continued to make significant contributions.

Read More

- Clash Royale Best Boss Bandit Champion decks

- Vampire’s Fall 2 redeem codes and how to use them (June 2025)

- World Eternal Online promo codes and how to use them (September 2025)

- How to find the Roaming Oak Tree in Heartopia

- Mobile Legends January 2026 Leaks: Upcoming new skins, heroes, events and more

- Best Arena 9 Decks in Clast Royale

- ATHENA: Blood Twins Hero Tier List

- Brawl Stars December 2025 Brawl Talk: Two New Brawlers, Buffie, Vault, New Skins, Game Modes, and more

- Clash Royale Furnace Evolution best decks guide

- What If Spider-Man Was a Pirate?

2025-04-29 03:02