Author: Denis Avetisyan

Integrating semantic understanding into robotic control systems is dramatically improving the speed and efficiency of complex manipulation tasks.

This review details how leveraging knowledge graphs within deep reinforcement learning frameworks enhances sample efficiency and performance for robotic manipulation.

Despite the promise of deep reinforcement learning (DRL) for complex robotic control, substantial sample complexity often hinders its practical deployment. This limitation motivates the research presented in ‘Boosting Deep Reinforcement Learning with Semantic Knowledge for Robotic Manipulators’, which proposes a novel integration of DRL with semantic knowledge derived from knowledge graph embeddings. By providing agents with contextual information, this approach achieves up to a 60% reduction in learning time and a 15 percentage point improvement in task accuracy for robotic manipulation-without increasing computational cost. Could leveraging broader semantic understanding unlock even greater efficiency and adaptability in future robotic learning systems?

The Inevitable Shift: From Control to Learning

Robot Learning represents a pivotal shift in robotics, moving beyond pre-programmed instructions toward systems capable of independently mastering new skills. This field endeavors to build agents – be they physical robots or software entities – that can learn through experience, adapting to the unpredictable nature of real-world environments. Unlike traditional robotic control, which relies on meticulously engineered sequences, Robot Learning algorithms enable agents to explore, experiment, and refine their actions, ultimately achieving proficiency in complex tasks without explicit human guidance. This pursuit leverages techniques from machine learning, control theory, and artificial intelligence, promising a future where robots can autonomously acquire and perform a wide range of skills in diverse and dynamic settings.

Conventional control systems, meticulously engineered for predictable outcomes, often falter when confronted with the messy reality of the physical world. These methods typically rely on precise models of the environment and the agent itself, assumptions quickly undermined by sensor noise, unforeseen obstacles, and the simple fact that conditions rarely remain static. This inherent fragility stems from an inability to generalize beyond the specific scenarios for which they were programmed; a robot trained to grasp a red block might struggle with a blue one, or fail entirely if the lighting changes. Consequently, a growing need exists for solutions that embrace adaptability, allowing agents to learn and refine their behavior in real-time, rather than being rigidly bound by pre-defined instructions. The pursuit of such adaptive solutions is driving innovation in areas like reinforcement learning and imitation learning, offering the potential to create truly robust and intelligent agents.

Deep Reinforcement Learning: A Necessary Complexity

Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) addresses limitations of traditional reinforcement learning by leveraging the representational power of deep neural networks. Historically, reinforcement learning relied on hand-engineered features to represent the state of the environment; DRL eliminates this requirement by enabling agents to directly process raw, high-dimensional sensory input such as images or audio. The deep neural network acts as a function approximator, learning to map states to either a value function – predicting the expected cumulative reward – or a policy – defining the optimal action to take in a given state. This capability is crucial for tackling complex tasks where manual feature engineering is impractical or impossible, allowing DRL agents to learn directly from the environment without explicit state representation.

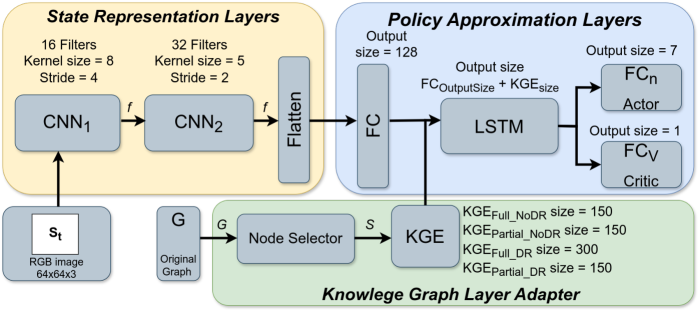

The Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) Agent Architecture specifies the neural network configurations used to estimate both the Value Function and the Policy. The Value Function, typically represented as [latex]V(s)[/latex] or [latex]Q(s,a)[/latex], predicts the expected cumulative reward from a given state or state-action pair. The Policy, denoted as [latex]\pi(a|s)[/latex], defines the probability distribution over actions given a state. Common architectures include Deep Q-Networks (DQNs), which approximate the Q-function using a deep neural network, and Actor-Critic methods, employing separate networks for the Policy (Actor) and Value Function (Critic). The network structure – including layer types (e.g., convolutional, recurrent, fully connected), activation functions, and hyperparameter settings – directly influences the agent’s ability to generalize from observed data and learn effective control strategies.

The core of deep reinforcement learning involves an agent iteratively interacting with a virtual environment to accumulate experience. This interaction generates a trajectory, which is a sequential record of the agent’s states, the actions taken in each state, and the resulting rewards received. Each step in the trajectory consists of the agent observing the current state [latex]s_t[/latex], selecting an action [latex]a_t[/latex] based on its current policy, and transitioning to a new state [latex]s_{t+1}[/latex] as defined by the environment’s dynamics. The environment then provides a scalar reward [latex]r_t[/latex] quantifying the immediate benefit or cost associated with the transition. This sequence of [latex]s_t, a_t, r_t, s_{t+1}[/latex] is repeated numerous times, forming the dataset used to train the deep neural network that approximates the optimal policy or value function.

The Reward Function is a critical component of Deep Reinforcement Learning, quantitatively defining the goal of the agent within its environment. It maps each state-action pair to a scalar reward value, providing feedback that guides the learning process. A properly designed Reward Function incentivizes desired behaviors and discourages undesirable ones; its scale and formulation directly influence the speed and stability of learning. The State Space defines all possible situations the agent can encounter, while the Action Space defines all possible actions the agent can take; the Reward Function must operate within these defined spaces to provide meaningful signals for policy optimization. Incorrectly specified rewards can lead to unintended consequences, where the agent exploits loopholes to maximize reward without achieving the intended objective.

Building Robustness: The Inevitable Dance with Uncertainty

The Asynchronous Advantage Actor-Critic (A3C) algorithm facilitates parallel training of Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) agents by employing multiple worker agents that independently collect experiences and update a global model. Each worker operates in its own copy of the environment, generating trajectories concurrently. These trajectories are then used to compute gradients, which are asynchronously applied to the global model, avoiding the need for synchronization and reducing training time. This parallelization effectively increases the sample throughput, allowing the agent to learn more quickly and efficiently than with single-agent training methods. The asynchronous updates also introduce a form of decorrelation between updates, potentially improving exploration and preventing premature convergence.

The General Advantage Estimator (GAE) is a key component of the Asynchronous Advantage Actor-Critic (A3C) algorithm used to reduce the variance of policy gradient methods. Rather than solely relying on Monte Carlo returns, GAE calculates an estimate of the advantage function – the difference between the expected return of an action and the value function. This is achieved by weighting the discounted rewards over multiple timesteps, controlled by parameters γ (discount factor) and λ (GAE parameter). A λ of 1 corresponds to Monte Carlo returns, while a value of 0 approximates a one-step Temporal Difference (TD) error. By balancing bias and variance through the λ parameter, GAE provides a more stable and efficient estimate of the relative benefit of taking a specific action in a given state, leading to improved policy updates and faster learning.

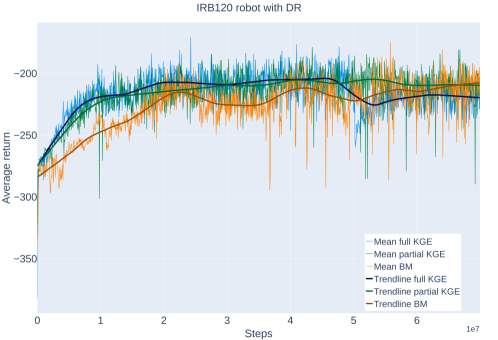

Domain randomization is a technique used to enhance the generalization capability of reinforcement learning agents by training them in a diverse set of simulated environments. This involves randomly varying parameters within the simulation, such as lighting conditions, object textures, friction coefficients, and even the agent’s own physical properties like mass or actuator strength. By exposing the agent to this variability during training, it learns to develop policies that are robust to changes in these parameters, ultimately improving its performance when deployed in a real-world environment or an environment with unseen conditions. The core principle is that the agent learns to focus on the essential aspects of the task, rather than overfitting to the specifics of a single training scenario.

The RMSprop optimizer is an adaptive learning rate algorithm designed to accelerate and stabilize training in deep reinforcement learning. Unlike traditional stochastic gradient descent (SGD) which utilizes a single learning rate for all parameters, RMSprop maintains a per-parameter learning rate. This is achieved by dividing the learning rate by the root mean square of recent gradients for that parameter. [latex] \text{RMSprop} = \frac{\alpha}{\sqrt{\epsilon + v_{t-1}}} [/latex], where α is the global learning rate, ε is a small constant to prevent division by zero, and [latex] v_t [/latex] is an exponentially decaying average of squared gradients. This adaptive adjustment effectively normalizes the gradient, allowing for larger updates in dimensions with infrequent gradients and smaller updates in dimensions with frequent gradients, thereby improving convergence speed and robustness.

Infusing Agents with Foresight: The Power of Prior Knowledge

The incorporation of Knowledge Graphs into Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) architectures significantly enhances an agent’s ability to learn and adapt within complex environments by providing crucial contextual information. Unlike traditional DRL methods that rely solely on raw sensory inputs, this approach equips the agent with a structured understanding of its surroundings, fostering improved sample efficiency. Studies demonstrate that agents leveraging Knowledge Graphs require substantially less training data to achieve comparable, and often superior, performance; learning times have been reduced by as much as 60% in certain scenarios. This acceleration stems from the agent’s capacity to generalize learned knowledge to novel situations, effectively bypassing the need for extensive trial-and-error exploration. By grounding actions in a pre-existing knowledge base, the agent can more efficiently navigate ambiguous or incomplete data, ultimately leading to more robust and adaptable behaviors.

Knowledge graph embeddings represent a powerful technique for imbuing artificial intelligence agents with the ability to understand and leverage relationships within their environment. These embeddings transform entities – objects, concepts, or locations – and their connections into numerical vectors, capturing semantic meaning in a way that computational systems can process. Rather than treating information as isolated data points, the agent can utilize these vector representations to infer connections, predict outcomes, and reason about the world in a manner analogous to human understanding. For example, an agent might learn that ‘cup’ is related to ‘table’ and ‘drink’, allowing it to anticipate the presence of a drink on or near a table, or to deduce the function of an unfamiliar object based on its associations within the knowledge graph. This capability moves beyond simple pattern recognition, enabling agents to generalize knowledge to novel situations and navigate complex environments with greater efficiency and robustness.

Robotic agents often struggle when interpreting the complexities of real-world sensory data, particularly ambiguous visual input like RGB images. A solution lies in supplementing this raw data with a structured knowledge base, effectively providing contextual understanding. By grounding actions in pre-existing knowledge, the agent can move beyond simply recognizing pixels to understanding what those pixels represent – identifying objects, predicting their behavior, and planning appropriate responses. This approach mitigates the need for exhaustive training on every possible scenario, allowing the agent to generalize more effectively and make informed decisions even when faced with incomplete or noisy information. The result is a more robust and adaptable system capable of operating reliably in dynamic and unpredictable environments, even with imperfect sensory input.

Recent advancements indicate a substantial capacity for robotic agents to exhibit more sophisticated behaviors when equipped with integrated knowledge systems. Empirical evidence demonstrates this potential, with the TIAGo robot achieving a 20% performance increase-reaching 79% accuracy-when utilizing domain randomization alongside knowledge integration, a significant leap from the 62% accuracy observed in baseline models. Further corroborating these findings, the IRB120 robot also benefitted, attaining an impressive 86% accuracy, highlighting the broad applicability of this approach and suggesting that grounding robotic actions in structured knowledge not only improves performance but also unlocks the possibility of more complex and nuanced interactions with dynamic environments.

The pursuit of robust robotic systems often fixates on intricate algorithms, yet overlooks the foundational importance of representing the world itself. This work, integrating semantic knowledge into deep reinforcement learning, echoes a fundamental truth: systems aren’t built, they grow from understanding. The improvement in sample efficiency isn’t merely a technical achievement; it’s a testament to the power of providing the agent with a richer, more meaningful context. As Henri Poincaré observed, “It is through science that we arrive at truth, but it is through chaos that we arrive at creation.” This echoes the core idea; a system’s ability to navigate complex manipulation tasks isn’t solely about the learning algorithm, but also about the agent’s ‘understanding’ of the environment, allowing it to move beyond rote learning towards genuinely adaptive behavior. Order, in this case, is simply a temporary respite from the inevitable chaos of real-world interaction.

The Looming Architecture

The grafting of symbolic knowledge onto the restless tendrils of deep reinforcement learning feels less like a solution and more like a temporary reprieve. This work, in demonstrating improved sample efficiency, merely delays the inevitable reckoning with the brittleness inherent in all learned systems. Each successful manipulation, guided by a knowledge graph, is a prophecy of the inevitable failure when confronted with novelty – a situation not anticipated within the curated semantic space. The question isn’t whether the system can learn, but what unforeseen corner of the world will expose the limitations of its understanding.

Future efforts will likely focus on dynamic knowledge integration – allowing the agent to not just use a knowledge graph, but to grow one. Yet, even this feels like building a more elaborate cage. The true challenge lies in abandoning the notion of a fixed ‘knowledge’ altogether, and embracing the inherent ambiguity of interaction. A system that doesn’t merely react to what it knows, but anticipates what it doesn’t know, is a distant, perhaps illusory, goal.

One suspects the relentless pursuit of ‘generalization’ is a fool’s errand. Systems aren’t built, they’re grown. And growth, by its very nature, is messy, unpredictable, and inevitably leads to decay. The next iteration won’t be about better algorithms, but a quiet acceptance of impermanence.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.16866.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- VCT Pacific 2026 talks finals venues, roadshows, and local talent

- EUR ILS PREDICTION

- Lily Allen and David Harbour ‘sell their New York townhouse for $7million – a $1million loss’ amid divorce battle

- eFootball 2026 Manchester United 25-26 Jan pack review

- SEGA Football Club Champions 2026 is now live, bringing management action to Android and iOS

- Will Victoria Beckham get the last laugh after all? Posh Spice’s solo track shoots up the charts as social media campaign to get her to number one in ‘plot twist of the year’ gains momentum amid Brooklyn fallout

- Vanessa Williams hid her sexual abuse ordeal for decades because she knew her dad ‘could not have handled it’ and only revealed she’d been molested at 10 years old after he’d died

- ‘This from a self-proclaimed chef is laughable’: Brooklyn Beckham’s ‘toe-curling’ breakfast sandwich video goes viral as the amateur chef is roasted on social media

- The Beauty’s Second Episode Dropped A ‘Gnarly’ Comic-Changing Twist, And I Got Rebecca Hall’s Thoughts

- How to have the best Sunday in L.A., according to Bryan Fuller

2026-01-26 21:24