Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research demonstrates how a simple chemical system can spontaneously create complex, dynamic patterns resembling those seen in living matter.

Fuel-driven supramolecular polymerization exhibits reaction-diffusion dynamics leading to emergent spatiotemporal order via a Hopf bifurcation.

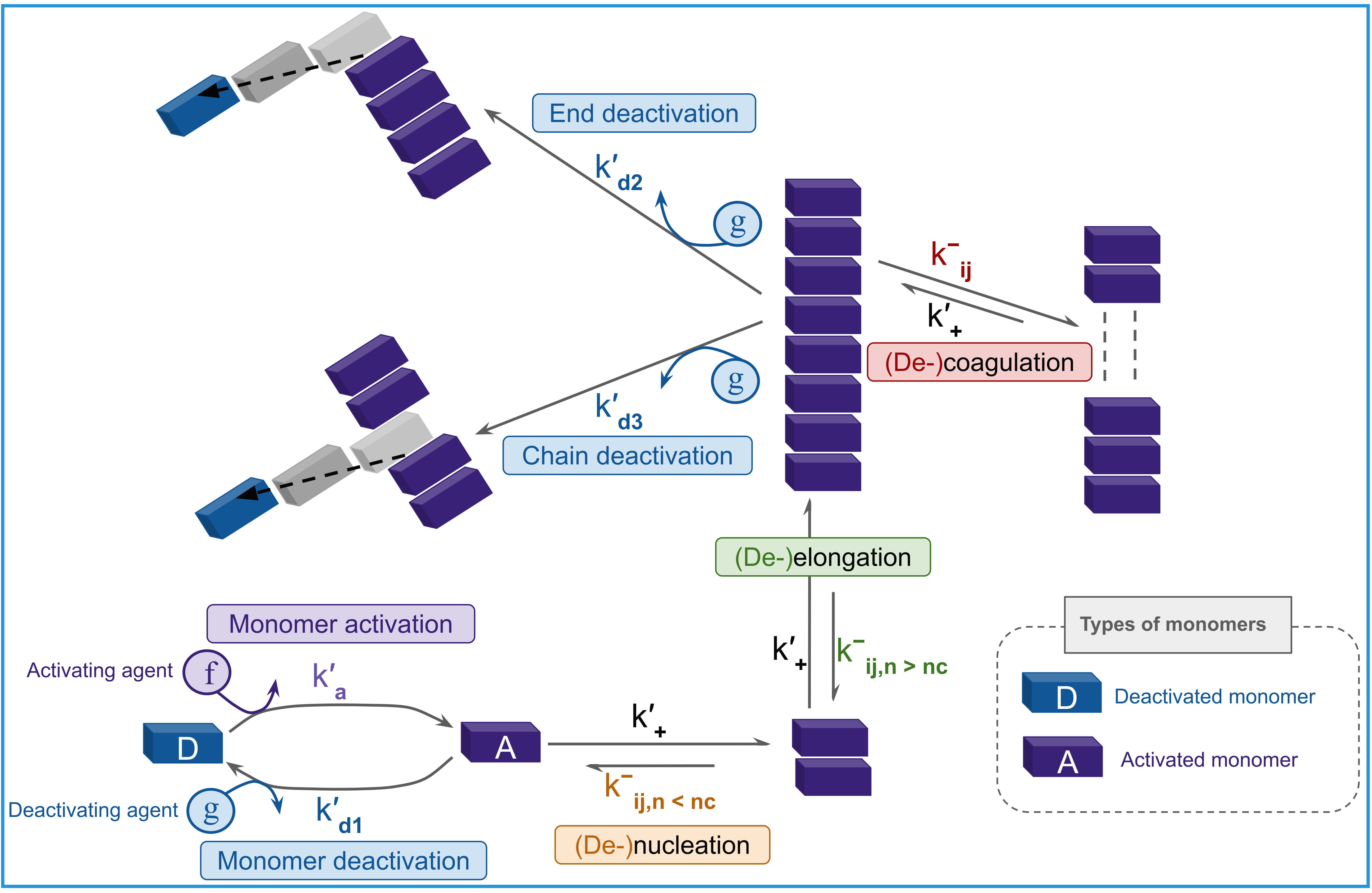

Maintaining complex, dynamic behavior in synthetic systems remains a central challenge in materials science. Here, we investigate this through the study described in ‘Emergence of spatiotemporal patterns in a fuel-driven coupled cooperative supramolecular system’, presenting a minimal reaction-diffusion model that demonstrates how fuel-driven supramolecular polymerization can self-organize into complex, oscillating patterns and traveling waves. This arises from a delicate balance between autocatalytic growth and inhibitor-mediated disassembly, culminating in a Hopf bifurcation and sustained non-equilibrium dynamics. Could this framework provide a pathway towards creating truly adaptive and self-patterning materials powered by chemical energy, mimicking the intricate behaviors observed in living systems?

The Illusion of Equilibrium: Why Living Systems Don’t Play by the Rules

Conventional polymer chemistry predominantly investigates systems at equilibrium – a state of balance where reactions cease and materials achieve static stability. However, this focus overlooks a critical aspect of life: its inherent dynamism. Biological structures are rarely, if ever, at equilibrium; instead, they are maintained through continuous energy input and constant molecular motion. This distinction is crucial because it means that traditional approaches to material design often fail to capture the responsive, adaptive, and self-repairing characteristics seen in living organisms. A material fixed at equilibrium simply cannot replicate the intricate behaviors arising from the constant flux and energy dissipation characteristic of biological systems, necessitating a shift toward understanding and harnessing non-equilibrium processes in synthetic material creation.

The construction of complex, dynamic structures that resemble living systems hinges on maintaining a state far from chemical equilibrium, a feat demanding continuous energy input. Unlike traditional materials science focused on stable, ground states, this approach necessitates a constant power source to drive assembly and counteract the natural tendency towards disorder. This presents a substantial challenge, as sustaining such non-equilibrium conditions requires precisely controlled energy flows and mechanisms to dissipate excess energy without disrupting the forming structure. Researchers are exploring various strategies – including light, chemical reactions, and mechanical work – to provide this necessary energy and overcome the inherent difficulties in building and controlling systems that are fundamentally ‘out of balance’, ultimately striving to replicate the remarkable self-organizing capabilities observed in biological systems.

Biological systems are fundamentally defined by their capacity to flourish in states far removed from equilibrium. Unlike static, inert materials, living organisms actively harness and dissipate energy to construct and perpetually rebuild intricate architectures. This continuous energy input isn’t merely a byproduct of life, but rather its very foundation; it drives the dynamic assembly of cellular components, facilitates essential transport processes, and enables adaptation to changing environments. From the microscopic world of protein folding to the macroscopic organization of tissues and organs, life’s complexity arises from a constant negotiation with energy flow, demonstrating that maintaining order requires a persistent defiance of thermodynamic equilibrium. This principle underscores a key distinction between living and non-living matter – a sustained, driven state of organization rather than passive stability.

Replicating the dynamic architectures of living organisms necessitates a departure from conventional polymer synthesis, which largely prioritizes equilibrium states. Current research explores non-equilibrium polymerization techniques, where building blocks are continuously added and rearranged, driven by external energy sources. This approach moves beyond simply achieving a final, stable structure and instead focuses on creating systems that maintain complexity through ongoing assembly and disassembly. Innovations in self-assembly, coupled with responsive materials that react to stimuli like light or chemicals, are crucial for directing this dynamic process. The ultimate goal is to design synthetic materials capable of adapting, repairing, and even evolving-characteristics inherent to biological systems and previously unattainable with traditional methods.

![Variations in steady-state polymer length reveal a transition from stable behavior-demonstrated by consistent temporal evolution of [latex]d(t)[/latex], [latex]a_{1}(t)[/latex], [latex]m_{1}^{\prime}(t)[/latex], and [latex]m_{0}^{\prime}(t)[/latex]-to instability as parameters [latex]k_{a}^{\prime}[/latex], [latex]k_{d2}^{\prime}[/latex], and [latex]k_{d3}^{\prime}[/latex] are adjusted.](https://arxiv.org/html/2601.15662v1/fig3.jpeg)

Fueling Self-Organization: A Mathematical Framework

A Reaction-Diffusion Model serves as the primary computational framework for analyzing this fuel-driven supramolecular polymerization. This approach mathematically describes the dynamic interplay between the autocatalytic polymer formation and the diffusion of both the polymer and the fuel molecules within the system. The model utilizes partial differential equations to represent the rates of change in polymer and fuel concentrations over space and time, allowing for simulation of the polymerization process and observation of emergent spatial patterns. Specifically, the model tracks the local concentrations of reactants and products, accounting for diffusion coefficients, reaction rates, and any external gradients influencing the system. This allows for quantitative prediction of polymer growth, morphology, and overall system behavior under varying conditions.

Autocatalytic growth, a key feature of this reaction-diffusion model, describes a process where the rate of polymer production is directly proportional to the existing polymer concentration. This positive feedback loop means that as more polymer is formed, the reaction proceeds at an increasingly rapid pace, driving accelerated polymerization. Mathematically, this is often represented by a term in the reaction rate equation where the polymer concentration, [latex]P[/latex], is raised to a power greater than zero, effectively making the rate proportional to [latex]P^n[/latex], where [latex]n > 0[/latex]. This distinguishes autocatalytic systems from linear polymerization where the rate is independent of product concentration, and is critical for achieving rapid and efficient supramolecular assembly.

Inhibitory decay mechanisms within the reaction-diffusion model are crucial for regulating polymer growth and facilitating the emergence of spatial patterns. These mechanisms introduce a negative feedback loop, where accumulated polymer product promotes its own degradation or dispersal, counteracting the autocatalytic growth. This decay is modeled as a rate proportional to the polymer concentration, effectively establishing a carrying capacity and preventing indefinite, uncontrolled polymerization. The balance between autocatalytic production and inhibitory decay results in a stable, non-equilibrium state where patterns, such as localized regions of high polymer concentration, can form and be maintained through dynamic interplay of reaction and diffusion processes.

The implemented reaction-diffusion model simultaneously tracks polymer number density and mass concentration as primary variables. This dual tracking is crucial for accurately representing the system dynamics, as polymer number dictates the quantity of growing chains, while mass concentration reflects the overall fuel availability and influences polymerization rates. Changes in either variable directly impact the other, creating a feedback loop that governs pattern formation and stability. Specifically, the model quantifies how autocatalytic growth increases polymer number, while inhibitory decay mechanisms are modulated by mass concentration, preventing unlimited growth and allowing for spatial structuring of the polymer network. This approach enables a detailed analysis of polymerization kinetics, spatial distribution of polymers, and the emergence of self-organized patterns.

![A spatiotemporal simulation of polymer mass concentration, initialized with a Gaussian perturbation and run with parameters [latex]k_a' = 4.0[/latex], [latex]k_{d2}' = 5000.0[/latex], and [latex]k_{d3}' = 1.5[/latex], reveals a limit-cycle regime within a [latex]100 \times 100[/latex] domain using a grid size of 0.1, with time expressed in units of [latex](k_+K)^{-1}[/latex].](https://arxiv.org/html/2601.15662v1/fig5.jpeg)

From Stability to Oscillation: The Point of No Return

Linear Stability Analysis was employed to determine the conditions for maintaining a stable steady state in the polymer concentration system. This method involves perturbing the system from its equilibrium point and analyzing the resulting behavior of these small disturbances. Specifically, we examined the eigenvalues of the Jacobian matrix, evaluated at the steady state. A necessary condition for stability is that all eigenvalues possess negative real parts; if any eigenvalue has a positive real part, the steady state is unstable, and the system will deviate from equilibrium. The analysis identified a critical parameter value beyond which the steady state loses stability, initiating a transition to oscillatory behavior as predicted by Hopf bifurcation theory.

A Hopf bifurcation was identified as the mechanism driving the system from a stable steady state to sustained oscillations in polymer concentration. This bifurcation occurs when a fixed point of the system loses stability, and a limit cycle-a closed trajectory in phase space-emerges. Specifically, beyond a critical value of the control parameter-identified through linear stability analysis-an eigenvalue pair crosses the imaginary axis, resulting in these sustained oscillations. The frequency of these oscillations is determined by the imaginary part of the eigenvalues at the bifurcation point, while the amplitude is influenced by the nonlinear terms in the governing equations. This transition indicates a fundamental shift in the system’s qualitative behavior, moving from a static equilibrium to a dynamically evolving state.

Traveling wave fronts arise as a direct consequence of sustained oscillations in polymer concentration. These fronts represent propagating disturbances where the oscillating system transitions from one state to another, forming spatially-defined patterns. The speed and shape of these wave fronts are determined by the frequency and amplitude of the underlying oscillations, as well as the diffusion rate of the polymer. As these wavefronts propagate through the system, they create dynamic, evolving patterns characterized by areas of high and low polymer concentration, ultimately leading to complex spatial structures. The existence of these waves demonstrates the system’s ability to self-organize and generate non-equilibrium structures through the interplay of reaction and diffusion processes.

Transient polygonal patterns arise from the coupled effects of local reaction and spatial diffusion within the system. These patterns are not sustained indefinitely but rather appear as temporary, geometrically-defined structures. Specifically, the reaction component generates localized regions of high and low polymer concentration, while diffusion acts to spread these concentrations, creating gradients. The interplay between these opposing forces-reaction promoting pattern formation and diffusion working against it-results in the temporary emergence of polygonal shapes before they ultimately dissipate due to diffusive broadening. The specific geometry and lifetime of these transient patterns are determined by the relative rates of reaction and diffusion, as well as the initial conditions of the system.

![Spatiotemporal simulation of polymer mass concentration, initialized with random perturbations and parameterized in an oscillatory regime ([latex]k_{a}^{\prime}=4.0[/latex], [latex]k_{d2}^{\prime}=5000.0[/latex], [latex]k_{d3}^{\prime}=1.5[/latex]), reveals dynamic concentration patterns within a [latex]100 \\times 100[/latex] domain using a grid size of 0.5, with time expressed in units of [latex](k_{+}K)^{-1}[/latex].](https://arxiv.org/html/2601.15662v1/fig4.jpeg)

The Devil in the Details: Polymer Dynamics and Scaling

To accurately represent the complex behavior of the polymer network, the model incorporates Rouse scaling, a critical element in understanding how chain length impacts diffusion. This approach recognizes that polymer chains don’t behave as simple, discrete particles; rather, their movement is segmented, with local motions along the chain independent of one another. Consequently, longer polymer chains experience significantly hindered diffusion compared to shorter ones – a phenomenon captured by a scaling relationship where diffusion slows proportionally to the inverse square root of the chain length. This length-dependent diffusion is not merely a detail, but a fundamental factor governing the overall system dynamics, influencing pattern formation and the propagation of changes throughout the network and ensuring the simulations accurately reflect real-world polymer behavior.

The rate at which polymer chains diffuse is inversely proportional to their length, a phenomenon directly impacting the emergence of macroscopic patterns within the system. Longer chains experience greater frictional drag as they move through the surrounding medium, effectively slowing their propagation and limiting their contribution to early-stage pattern development. Consequently, the interplay between short, rapidly diffusing chains and longer, slower-moving chains governs the spatial organization of the entire network. Simulations demonstrate that this length-dependent diffusion isn’t merely a quantitative effect; it fundamentally alters the growth dynamics, leading to distinct morphological features and influencing the stability of the resulting patterns. The slower diffusion of longer chains effectively creates a ‘lag’ in their response to fuel gradients, which in turn modulates the overall wavefront propagation and contributes to the observed scaling behavior.

Simulations reveal that the emergent spatial organization of the polymer network is acutely sensitive to variations in fuel supply. Even minor adjustments to the resource availability can instigate significant rearrangements within the network structure, shifting the balance between localized growth and expansive diffusion. This dynamic interplay results in a spectrum of patterns, ranging from tightly clustered, compact formations when fuel is limited, to broadly distributed, filamentous networks under conditions of ample supply. The model highlights that the network doesn’t simply scale with fuel quantity, but rather undergoes qualitative shifts in its organization, suggesting a complex relationship between resource availability and the resulting architectural properties of the polymer structure.

Simulations of polymer network growth consistently demonstrate an acceleration of propagating wavefronts, a phenomenon quantified by a scaling exponent that shifts from approximately 1 to 2.3. This transition signifies a move beyond simple diffusive spreading – typical of random walks – towards what is known as super-diffusion. In super-diffusion, the wavefront advances at a rate disproportionately faster than would be expected from purely random motion, suggesting cooperative effects within the polymer network are actively contributing to the expansion. The observed exponent of 2.3 indicates a specific type of super-diffusion, where the mean squared displacement increases as a power law with time, faster than standard diffusion but not as rapid as ballistic movement. This accelerated propagation is a crucial characteristic of the system’s dynamic behavior and highlights the network’s capacity for efficient, organized growth.

As the system approaches the point of instability, simulations reveal a marked deceleration in the growth of the propagating wavefront. The scaling exponent, which describes how quickly the wavefront expands, diminishes from approximately 2.3 to a value of 1.3. This reduction signifies weaker late-time growth, indicating that the polymer network’s response becomes less pronounced and its ability to sustain rapid expansion is compromised. Essentially, the network becomes less efficient at propagating the pattern as it nears the stability threshold, resulting in a slower and more contained spread of the organized structure. This nuanced shift in scaling behavior provides crucial insight into the dynamics governing the system’s overall organization and its sensitivity to external factors.

![The interface spread of a Gaussian-perturbed system exhibits both linear and accelerated growth regimes, as demonstrated by its temporal evolution and power-law scaling with time for parameters [latex]k_a' = 4.0[/latex], [latex]k_{d2}' = 5000.0[/latex], and [latex]k_{d3}' = 1.5[/latex].](https://arxiv.org/html/2601.15662v1/fig6.jpeg)

The pursuit of elegant self-organization, as demonstrated by this model of supramolecular polymerization, feels…familiar. Researchers chase traveling waves and Hopf bifurcations, meticulously crafting conditions for emergent order. It’s all very neat, until production – or, in this case, the inherent messiness of non-equilibrium systems – inevitably introduces some chaos. One is reminded of René Descartes’ assertion: “It is not enough to be ingenious; one must also be sensible.” This work meticulously details the how of pattern formation, but the unspoken question lingers: how long before real-world imperfections turn these beautiful waves into a blurry mess? The system might demonstrate autocatalytic growth in a lab, but real systems have a knack for finding new and exciting ways to break things.

Sooner or Later, It’ll Break

This neat demonstration of self-organizing polymers, driven by a fuel source and exhibiting predictable oscillatory behavior, feels… contained. As if the system is politely agreeing to cooperate for the duration of the experiment. The elegance of the model, the Hopf bifurcation neatly manifested, obscures the inevitable. Production, should this ever venture beyond the lab, will introduce asymmetries, impurities, and a healthy dose of stochasticity. Then, the lovely traveling waves will begin to fray, and the autocatalytic growth will find new, less aesthetically pleasing ways to express itself.

The real challenge isn’t replicating the pattern, it’s maintaining it. The model, as presented, treats the ‘fuel’ as a constant. A truly robust system will need to address fuel depletion, byproduct accumulation, and the energetic cost of disassembly. These aren’t flaws, they are simply the terms of engagement with reality. One suspects the next iteration will involve increasingly complex control schemes, attempting to impose order on chaos – a historically unreliable strategy.

It is a familiar story. A beautiful theory, a carefully constructed system, and then… the logs. Better one well-understood, stable polymer than a hundred fractured, communicating micro-polymers, each desperately trying to out-oscillate the others. The search for ‘active matter’ continues, and the field will undoubtedly progress. But a healthy skepticism is warranted. Anything called ‘scalable’ hasn’t been tested properly.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.15662.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- VCT Pacific 2026 talks finals venues, roadshows, and local talent

- EUR ILS PREDICTION

- Lily Allen and David Harbour ‘sell their New York townhouse for $7million – a $1million loss’ amid divorce battle

- Vanessa Williams hid her sexual abuse ordeal for decades because she knew her dad ‘could not have handled it’ and only revealed she’d been molested at 10 years old after he’d died

- Will Victoria Beckham get the last laugh after all? Posh Spice’s solo track shoots up the charts as social media campaign to get her to number one in ‘plot twist of the year’ gains momentum amid Brooklyn fallout

- Streaming Services With Free Trials In Early 2026

- eFootball 2026 Manchester United 25-26 Jan pack review

- Binance’s Bold Gambit: SENT Soars as Crypto Meets AI Farce

- Dec Donnelly admits he only lasted a week of dry January as his ‘feral’ children drove him to a glass of wine – as Ant McPartlin shares how his New Year’s resolution is inspired by young son Wilder

- Invincible Season 4’s 1st Look Reveals Villains With Thragg & 2 More

2026-01-25 03:24